Sullivan M, Nguyen-Truong C, Leung J. Teach-back method in presenting health promotion topics program: nursing collaboration with the Micronesian islander community organization and Micronesian islander parent leaders. HPHR. 2023;57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/EEE2

Corresponding Author: Dr. Connie K Y Nguyen-Truong, Email: [email protected]

1. Dr. Sullivan is the first author; 2. Dr. Nguyen-Truong is the co-first author and senior author.

The project was implemented in 4 virtual sessions using the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics. We used the Teach-Back Confidence and Commitment Scale, distance learning and open-ended items, and field notes and observations journal for evaluation. Participants used the Teach-Back Observation Tool to practice observing the presenter leveraging essential elements of the Teach-Back method.

MIPLs reported increased adoption and acceptance of the Teach-Back method to communicate health messages to their community and family members.

Health promotion topics identified by the group were presented using caring, respectful, plain language, and in a non-threatening manner as a vehicle to illustrate and evaluate using the established Teach-Back method tools

In earlier community-based participatory research in the United States Pacific Northwest, a Micronesian Islander-based nonprofit community organization and public Washington State University College of Nursing partnership identified a need with the Micronesian Islander Parent Leaders (MIPLs) from the Health and Education Program to learn communication techniques to prevent non-communicable diseases and advocate for access to quality health information for health promotion outreach.1,2 MIPLs are well-respected community leaders and elders who are resident representatives from diverse Island communities in Salem, Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. Salem, Oregon, is among the cities with the most substantial reported numbers of Micronesian and Pacific Islanders at 2,171.3. Micronesian and Pacific Islander cultural groups are tight-knit and demonstrate strong family relationships.2 The purpose of this article is to describe the Teach-Back method as an evidence-informed technique, important considerations when working with Micronesian and Pacific Islander communities, and the implementation and evaluation of the community participatory scholarly project on the use of the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics with MIPLs – a communicating health messages skill – as a program.

Academic nursing partners collaborated with a nonprofit to connect with MIPLs, holding meetings concerned about communication. About 40%-80% of medical information is forgotten almost immediately, and a recipient or learner often misremembers medical information that is recalled.4 The Teach-Back method is an evidence-informed technique for verifying a person’s understanding of the health messages received and reteaching or modifying if an agreement is not met and is a strategy for health literacy.5 A health message communicator or presenter asks a person to repeat the health messages they receive in their own words. 5 In the healthcare field, the Teach-Back method has been used mainly by primary providers to communicate health messages that clients can understand and ask clients to explain/teach-back healthcare messages in own words.6,7 Clients or family members who used the Teach-Back method improved their communication with healthcare providers.8 Researchers recommended that clients and family members use the Teach-Back method to improve their understanding of healthcare messages.8,9 Furthermore, the Teach-Back method can be used in community settings5 on topics such as diabetes10 and communicating with parents about children’s health issues8. Healthcare providers have used the Teach-Back method to communicate health messages via telephone, as in telehealth, to provide remote instead of in-person care.11 Use of Teach-Back is critical as a low-cost, effective method to improve health messaging, including in community settings.7 The Teach-Back method can be a helpful health promotion outreach communication skill in communicating health messages to their community.

There are important considerations when working with the Micronesian and Pacific Islander communities. There is a dearth of research on Micronesian and Pacific Islanders. Colonization and the resulting importation of Western foods, for example, Spam (type of processed meat), white rice, and high-fat turkey tail, contributed to the increase of non-communicable diseases among Micronesian and Pacific Islanders.12 Micronesian and Pacific Islanders in the United States often adopted the Standard American Diet, for example, processed foods, thereby increasing the risk across the lifespan of developing non-communicable diseases.13 Micronesian and Pacific Islanders have a higher rate of non-communicable infections, for example, diabetes than the other populations in North America.12 In part because of comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity, the COVID-19 pandemic has hit Micronesian and Pacific Islanders especially hard in the western United States.14 The incidence of mortality from COVID-19 among Micronesian and Pacific Islanders is 13% compared to 4% of other populations in North America.15 Micronesian and Pacific Islanders comprise 0.4% of the population in Oregon of the United States Pacific Northwest but represent nearly 3% of all COVID-19 infections.15 In Oregon, Micronesian and Pacific Islanders were three times more likely to be infected by COVID-1915 and had the highest mortality rate than other racial and ethnic groups.15,16

The existing community-academic partnership with MIPLs expanded to include collaboration with the academic Doctor of Nursing Practice student scholar Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) partner (hereafter referred to as FNP partner) on the Teach-Back Method Program community participatory scholarly project. We used the RE-AIM framework to guide this community participatory scholarly project.17 RE-AIM is reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. The RE-AIM framework has been used in community settings in various program planning and evaluation activities to implement research into community action,17-19 for example, dietary change, worksite health promotion, diabetes prevention, and exercise.17,18 Reach is the intended audience and the representativeness of participants.17 Evaluation of the implementation to examine effectiveness.17 Adoption is the setting, and organizational leadership and staff agree to initiate a program.17 Implementation is how a setting, organizational leadership, and staff deliver a program as intended and make adaptations.17 Maintenance is the sustained effectiveness at the participant level and sustained delivery at the setting.17 The community participatory scholarly project questions were: 1) How effective is the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics as a program using a distance learning format? and 2) Is the Teach-Back method as a program acceptable for communicating messages for MIPLs?

The community participatory scholarly project (#18011-001) was determined exempt by the Washington State University Human Research Protection Program, and the Washington State University College of Nursing ethical internal review committee approved it.

There were four (4) virtual sessions in the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics program, each lasting about one hour. Session 1 is Health Literacy and Use of the Teach-Back Method to Communicate Health Messages and was implemented in September 2020. Session 2 is Nutrition as a Tool to Reduce the Occurrence and Mitigate the Effects of Non-Communicable Diseases and was implemented at the start of October 2020. Session 3 is Designing a Simple Exercise Program and Using a Distance Learning Format and was implemented two weeks later in the same month. Session 4 is Healthy Cooking, Using Traditional Foods, and Introduction to Island Chefs, which was implemented in December 2020. The timeline was discussed and mutually agreed upon by the community-academic nursing partnership with MIPLs that worked during the COVID-19 pandemic to accommodate MIPLs’ work and parenting/caregiving schedules. Refer to Table 1 for the health promotion topics across the four virtual sessions and key contents and activities of the Teach-Back method program.

Table 1. Teach-Back Method in Presenting Health Promotion Topics Program: Virtual Sessions, Health Promotion Topics, and Key Content and Activities

Virtual Sessions and Health Promotion Topics

| Key Content and Activities |

Session One: Health Literacy and Use of the Teach-Back Method to Communicate Health Messages

|

|

Session Two: Nutrition as a Tool to Reduce the Occurrence and Mitigate the Effects of Non-Communicable Diseases

| Food as medicine and inflammation as a cause of chronic disease

|

Session Three: Designing a Simple Exercise Program and Using a Distance Learning Format

|

|

Session Four: Healthy Cooking, Using Traditional Foods, and Introduction to Island Chefs

| Why we eat and why cooking expresses love:

|

The community participatory scholarly project was held virtually via videoconference with 100% social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. The academic nurse partner and the Executive Director/community partner at the MI-based community organization obtained voluntary consent from MIPL participants prior to working with the FNP partner. Nine MIPLs were representatives from culturally diverse Island communities and identified as Chamarro, Chuukese, Kapingamarangi, Marshallese, and Pohnpeian. A staff member at the MI-based community organization provided voluntary consent and participated in session four. All MIPLs lived in Oregon. MIPLs held various parenting/caregiving roles, including a grandparent, mother, and/or aunt, and were beginning users of videoconference technology. MIPLs received a U.S. $25 shopping gift card and a meal per virtual session for four sessions, plus an additional U.S. $50 shopping gift card upon participation completion to honor and thank them for their time.

The community partner and academic nurse partner discussed and agreed that the FNP partner leads and be the presenter for the health promotion topics for all four virtual sessions for consistency. The facilitator presented live in each session and used a PowerPoint slide deck with text and images, interacted with Teach-Back essential elements and discussion, and provided resources, including videos (Table 1). At the end of each session, the FNP partner provided the presentation materials to all participants. The FNP partner engaged in ongoing debriefing with the community and academic nurse partners on culturally sensitive implementation with MIPLs. We used the self-administered Teach-Back Confidence and Commitment Scale with the addition of a distance learning format and open-ended item via the secure online Washington State University Qualtrics at the program’s baseline, mid-point, and end. We provided the Teach-Back Observation Tool to participants to practice observing the presenter on the essential elements via Qualtrics. At the end of sessions two, three, and four, we also added an open-ended item regarding the Teach-Back observational practice via Qualtrics. We used field notes and observation journals throughout sessions. The academic nurse partner offered assistance with online navigation.

We adapted the research-based Conviction and Confidence Scale from the health literacy tools developed by Abrams et al.20 of the Always Use Teach-Back! of the Institute for Healthcare Advancement21 and Agency for Health Research and Quality22. Abrams9 emphasized the Teach-Back method as effective communication to develop self-confidence to facilitate effective communication of health messages. We discussed and mutually agreed as a community-academic nursing partnership on the following. The Executive Director of the MI-based community nonprofit organization raised a concern that the term conviction in the scale name can be unclear in working with MIPLs. We adapted the name, Teach-Back Confidence and Commitment Scale, which consisted of 6 items.

We changed the term patient to people for a community setting. Two of the items were about the importance of using Teach-Back and how confident in using Teach-Back with a 10-point response scale, 0 = not important at all and 10 = very important: “On a scale from zero to ten, how convinced are you that it is important to use teach-back (ask people you are explaining key information to repeat it back in their own words)?” and “On a scale from zero to ten, how confident are you in your ability to use teach-back (ask people you are explaining key information to repeat it back in their own words)?” One item was about the frequency, “How often do you ask people you talk to in your community to explain back, in their own words, what they need to know or what to do to take care of themselves?” For this frequency item, there are five category response options: 2 months or more, less than 2 months, do not do it now but plan to in the next month, do not do it now but plan to in the next 2 to 6 months, or do not it now and do not plan to do this. One item was on the essential element of the Teach-Back method that was used in the past week, and eight essential elements were applicable for distance learning: used a caring tone of voice and attitude; displayed comfortable body language, made eye contact, and relaxed; used plain language; asked the person to explain in own words what they were told; used respectful, open-ended questions; avoided asking questions that can be answered with a yes or no; made sure that your message was clear; used reader-friendly print materials to support your message; and included family members or caregivers by saying hello or welcome if they were present.

We used the term respectful instead of non-shaming in the above element to clarify what that element meant to not come across as potentially shaming MIPLs and a community. We also added an open-ended item inviting participants to share their thoughts freely. The FNP partner added an item to assess how satisfied with the video conferencing technology as a distance learning method and used the following category response options: extremely satisfied, somewhat satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, extremely dissatisfied, or not applicable. The FNP partner verified and analyzed the quantitative data as descriptive statistics, analyzed for patterns in the open-ended data, and discussed findings with the community and academic nurse partners.

We also added an open-ended item to the Teach-Back Observation Tool, inviting participants to share their thoughts freely about the Teach-Back observational practices. The FNP partner analyzed the number of participants who completed the Teach-Back Observation Tool for practice and analyzed for patterns in the open-ended data, and discussed with the community and academic nurse partners.

The field notes-based data journal included observations, and the FNP partner manually documented during the sessions. Then, the FNP partner analyzed for patterns and discussed them with the community and academic nurse partners.

We adapted the Teach-Back Observation Tool as a health literacy tool developed by Abrams et al.20 of the Always Use Teach-Back! of the Institute for Healthcare Advancement23 and Agency for Health Research and Quality22. Participants used the Teach-Back Observation Tool to practice observing the presenter and the essential elements of the importance of using caring, respectful, and plain language and taking responsibility for assuring the person who receives the health message understands the message and can explain it back/teach it back in their own words.5,7,24 We discussed and mutually agreed as a community-academic nursing partnership on the following.

The Teach-Back Observation Tool consisted of nine items. Nine items refer to the presenter (speaker), “Did the speaker…”, as follows: 1) “…use a caring tone of voice and attitude?”; 2) “…display comfortable body language, make eye contact, and appear relaxed?”; 3) “…use plain words or language that you could understand?”; 4) “…use caring and respectful, open-ended questions?”; 5) “…avoid questions that could be answered with a simple “yes” or “no”?”; 6) “…try to make sure she or he was understood?”; 7) “…explain the idea and then check again to see if you were able to teach it back?”; 8) “…provide links to materials you may be able to use?”; 9) “…include family members if they were present on the video conferencing technology call by saying “hello” or “welcome”?.”

We used the term respectful instead of non-shaming to be explicit in what that element meant as to not come across as potentially shaming MIPLs and a community in item number four. For items number one through five, response options were “Yes,” “No,” or “Sometimes.” For numbers six through eight, response options were “Yes, “No,” or “Not applicable.”

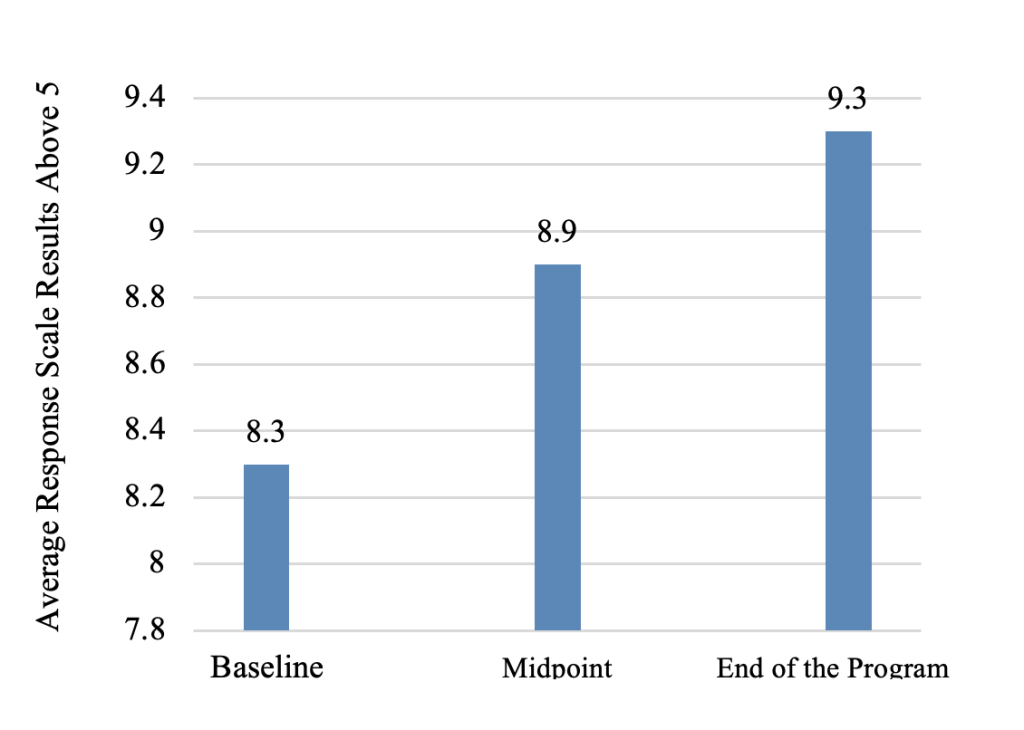

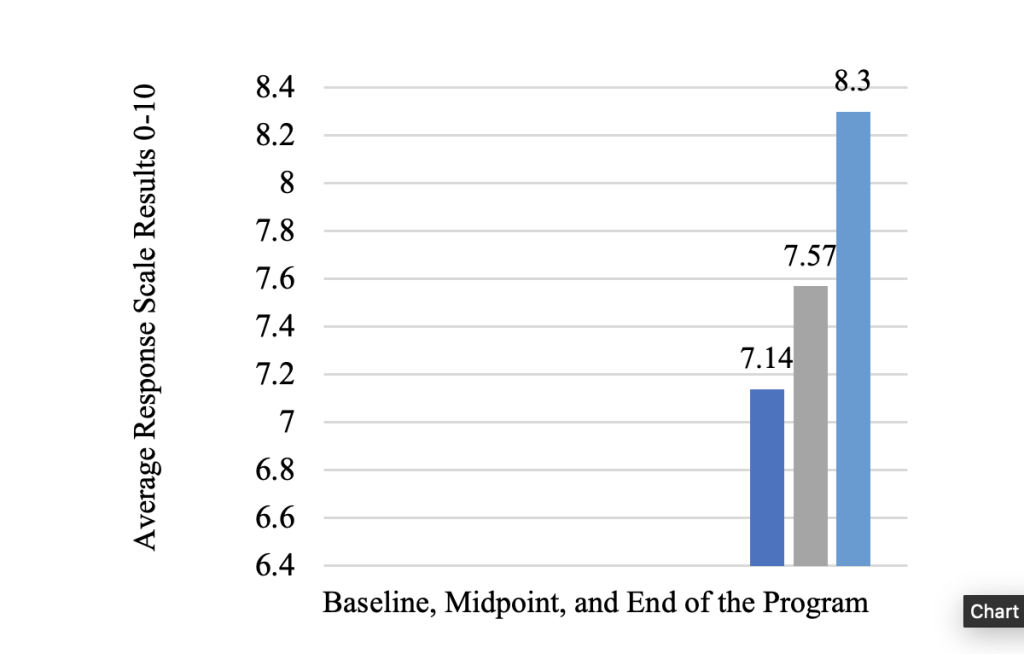

Participants reported how convinced they were that it was necessary to use Teach-Back (i.e., asking participants to repeat essential information in their own words). Refer to Figure 1. They had an increase in averages on a response scale of 8.3 at baseline, 8.9 at the midpoint, and 9.3 at the end of the program. Refer to Figure 2. Both the use and the acceptance of the Teach-Back method increased over time. About 57% of participants reported being confident using the Teach-Back method at baseline. By the end of the program, over 80% reported being confident in using the Teach-Back method. Refer to Table 2 for essential elements used in the Teach-Back method in the past week. All participants reported using the Teach-Back method. At the start of the Teach-Back Method in presenting health promotion topics program, two participants reported doing the following essential element, “Asked the person to explain in their own words what they were told” (i.e., Teach-Back process). Four participants reported doing that important element by the midpoint, and 100% (n = 10) of participants reported doing that element by the end of the program. Refer to Text Box 1 for response patterns of the added open-ended item to the Teach-Back Confidence and Commitment Scale.

Figure 1. Convinced that Teach-Back is Important

Note. n = 7 (N = 9) at baseline, n = 6 (N = 9) at midpoint, and

n = 10 (N = 10) at the end of the program.

Figure 2. Confident in Ability to Use the Teach-Back Method Over Time

Note. n = 7 (N = 9) at baseline, n = 6 (N = 9) at midpoint, and

n = 10 (N = 10) at the end of the program.

Table 2. Essential Elements Used in the Teach-Back Method in the Past Week

Essential Elements of the Teach-Back Method | Baseline N = 9

n | Midpoint N = 9

n | End of the Program N = 10

n |

Used a caring voice and attitude | 6 | 5 | 10 |

Displayed comfortable body language, make eye contact, relaxed | 4 | 4 | 9 |

Used plain language | 5 | 6 | 10 |

Asked person to explain in their own words what they were told (Teach-Back process) | 2 | 4 | 10 |

Used respectful, open-ended questions | 4 | 5 | 10 |

Avoid asking questions that can be answered with a yes or no | 2 | 3 | 2 |

Made sure that your message was clear | 4 | 1 | 6 |

Used reader-friendly print materials to support your message | 2 | 1 | 7 |

Text Box 1. Response Patterns of the Added Open-Ended Item to the Teach-Back Confidence and Commitment Scale

Most of the Responses were Expressions of Gratitude

Reponses Pertaining to What was Learned and Suggestions

When asked participants how satisfied they were with video conferencing technology for distance learning, 48.8% reported being either extremely satisfied or somewhat satisfied at baseline, and 50% reported being either extremely satisfied or somewhat satisfied at the midpoint. At the end of the program, 73% reported being extremely satisfied with video conferencing technology for distance learning, and 18% reported being somewhat satisfied. Open-ended responses were on gratitude and what was learned and suggestions on using the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics as a program.

Over time, the participants used the Teach-Back Observation Tool as practice during the virtual sessions to assess the presenter’s performance based on their ability to use the Teach-Back essential elements when presenting health topics/health messages. Seven participants at session 2, seven at session 3, and 10 at session 4 completed the Teach-Back Observation Tool for practice. Open-ended responses were on gratitude and what was learned and suggestions on using the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics as a program. Refer to Text Box 2 for response patterns of the added open-ended item on observational practice to the Teach-Back Observation Tool.

Text Box 2. Response Patterns of the Added Open-Ended Item on the Observational Practice to the Teach-Back Observation Tool

Most of the Responses were Expressions of Gratitude

Reponses Pertaining to Learning and Suggestions

The technical difficulty involved static background sound in the first virtual session. Another technical problem was not seeing the presenter’s face despite the video being turned on in session two. Participants verbalized having learned the importance of using the mute feature to turn off their microphones to help remove background sound and how to do this during sessions. One older participant initially depended upon the skills of their older grandchild to assist them with the video conferencing connection and progressed in their ability to use the video conferencing technology features, in particular turning on the microphone to speak and turning off when done speaking. The same older MIPL needed help from the academic partner with online navigation of the Qualtrics. Participants demonstrated increased use of reaction feature tools such as the thumbs-up, clapping icon, and hand-raise features over time.

This community participatory scholarly project aimed to describe the use of the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics with MIPLs – a communicating health messages skill – as a program. We answered two central questions on using a distance learning format and accepting the Teach-Back method as a program for communicating messages for MIPLs.

All participants were previously gathering in-person pre-COVID-19 pandemic and then needed to pivot to 100% use of videoconferencing technology during the pandemic. This can be challenging for beginning users across all educational sectors.25 The results indicate that acceptance of video conferencing technology improved over time. Participants increased using reaction feature tools such as the thumbs-up, clapping icon, and hand-raise features. The academic nurse partner offered assistance with online navigation, with one older MIPL needing help. The estimated completion time was 5 minutes, and the range of completion was between five and 15 minutes for the questionnaire and practice tool. Overall, these enhanced the virtual sessions as interactive and added to the inclusive nature of the health promotion topics presentation. By the end of the program, participants agreed that the video conferencing technology was an acceptable distance learning format to present and receive health promotion information despite the occasional technical difficulties in earlier virtual sessions.

The intention of having the FNP partner be the presenter for all virtual sessions was to have consistency. This helped to build trust and rapport at the start of the Teach-Back in presenting the health promotion topics program. We encouraged participants to use their voices and to complete the anonymous questionnaires. There was an increase in participants having completed the Teach-Back Observation Tool for practice across the virtual sessions. In a question regarding how confident they were to use the Teach-Back method, none of the participants chose less than five out of 10 on the response scale. There was an increase in confidence in using the Teach-Back method by the end of the program. This can also explain why there is acceptance of the Teach-Back method. By the end of the program, the responses suggest using Teach-Back as a method that works to communicate health messages for MIPLs and their respective Micronesian Island community and families.

The ongoing partnership continues to bring diverse perspectives across disciplines and sectors to address a community-identified need and extend the reach of health promotion to diverse Islander communities. Recommendations for future work include building upon this community participatory scholarly project and expanding on the Teach-Back method in group activities and meetings. This can consist of practicing role-plays with more healthcare providers, such as nursing, and using the Teach-Back method with a healthcare provider for mutual learning and discussion. For example, a scenario might be an MIPL attending a maternal health visit virtually or in person and asking a healthcare provider: “Do you mind if I teach you back what you just told me?” In doing so, this can be empowering, where they could show a healthcare provider what important health messages could be communicated differently for clear understanding. More investigative work can be done to build confidence in using telehealth options to receive healthcare remotely to access healthcare and quality health messages. The Teach-Back Conviction and Confidence Scale and the Teach-Back Observation Tool were initially developed in the context of English-speaking healthcare providers. More work is needed with considerations for diverse cultural contexts. For example, an essential element of the Teach-Back method, “Avoid asking questions that can be answered with a yes or no,” did not show an increase in use by the end of the program. A possible explanation is that this question can be challenging to understand. It may not align with a storytelling communication style identified and found in prior community-based participatory research studies working with Micronesians and Pacific Islanders.1,2,26

A community-academic nursing partnership implemented this community participatory scholarly project in 4 virtual sessions using the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics as a program. MIPLs adopted and accepted the Teach-Back method to communicate health promotion messages directly to their community and families. Health promotion topics identified by the group were presented using caring, respectful, plain language, and in a non-threatening manner as a vehicle to illustrate and evaluate using the established Teach-Back method tools.

Dr. Mari Sullivan: Led the Teach-Back method in presenting health promotion topics program and evaluated the community participatory scholarly project that was done as a part of the Doctor of Nursing Practice Program in partnership with an existing Washington State University College of Nursing and Micronesian Islander Community organization partnership, conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, project administration, and funding acquisition. Dr. Connie K. Y. Nguyen-Truong: Primary project mentor from organization; conceptualization; validation; investigation; resources; writing – review, revising, editing, and drafting; visualization; supervision, and funding acquisition. Dr. Jacqueline Leung: Secondary project mentor from organization; conceptualization; validation, investigation, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition.

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

This work was supported in part by the following grant funding awards. Dr. Jacqueline Leung and Dr. Connie K. Y. Nguyen-Truong received the Health and Education Fund Impact Partnerships Grant #19-02778 that funded in part the project, including Northwest Health Foundation, Meyer Memorial Trust, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Care Oregon, and Oregon Community Foundation, and also the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon through the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation. Dr. Connie K. Y. Nguyen-Truong, Dr. Mari Sullivan, and Dr. Jacqueline Leung received the Delta Chi Chapter-at-Large Scholar Award Grant of Sigma Theta Tau International that also partially funded the project. The authors are grateful to the Micronesian Islander Parent Leaders from the Health and Education Program for engagement. The authors thank Professor Dr. Janet Purath for overseeing the project at WSU Health Sciences Spokane, College of Nursing, Doctor of Nursing Practice Program. The authors are appreciative of Dr. Kandy S. Robertson PhD, Scholarly Professor in English and Washington State University Vancouver Writing Center Coordinator for editing assistance on an earlier version. The authors are also appreciative of the HPHR Journal Editorial Team and anonymous peer reviewers.

Dr. Mari Sullivan is a Family Nurse Practitioner in the Health Clinic at Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe in Kingston, Washington. Dr. Sullivan graduated in 2021 with a Doctor of Nursing Practice degree from the College of Nursing at Washington State University. She is a member of Sigma Theta Tau. Dr. Sullivan received an MSN degree, Family Nurse Practitioner in 1988 at Yale University, and also received an MSN, Community Health/Family Practice at the same university.

Dr. Connie K Y Nguyen-Truong (she/her/they) is a tenured Associate Professor at Washington State University, Department of Nursing and Systems Science, College of Nursing in Vancouver. She is recognized as a Martin Luther King Jr. Community, Equity, and Social Justice Faculty Honoree. She is a Fellow of the National League for Nursing Academy of Nursing Education and American Academy of Nursing. Dr. Nguyen-Truong’s research is across sectors and multidisciplinary, and with community and health organizations and leaders, community health workers, students, and faculty. Areas include health promotion and health equity, culturally specific data; immigrants, refugees, and marginalized communities; community-based participatory research/community-engaged research; parent leadership and early learning; diversity and inclusion in health-assistive and technology research including adoption; and cancer control and prevention. Dr. Nguyen-Truong received her PhD in Nursing, including health disparities and education, and completed a Post-Doctoral Fellowship in the Individual and Family Symptom Management Center at Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing.

Dr. Jackie Leung (she/they) is the Executive Director of the statewide nonprofit, the Micronesian Islander Community (MIC), and is an Assistant Professor at Linfield University. Jackie’s background is in public health advocacy, policy, and research. Her professional experience includes working in perinatal healthcare, Medicaid, early childhood education, healthcare access, chronic diseases, COVID-19 wrap-around services, and leadership pathways for community health workers. She serves in several leadership positions, including co-chairing the Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs and a traditional health worker representative on the Oregon Maternal Mortality & Morbidity Committee. In her free time, Jackie enjoys spending time with her family and long scenic drives along the coast and through the agricultural landscapes that make Oregon the beauty it is today.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.