Wothe J, Schoephoerster J, Lundeen A, Silva R. Effect of substance use disorder on detection and treatment of COVID-19 in a large county jail. HPHR. 2022;50. 10.54111/0001/WW4

Carceral facilities are epicenters of COVID-19 transmission, and the interplay of substance use disorder has created an additional challenge in detection. Our study describes outcomes related to the overlap of COVID-19 and substance use in a large county jail.

This is a retrospective study of adults who tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated at a county jail in 2020. Basic descriptive statistics were performed as well as two-tailed t-tests and chi-square analysis to determine the significance of differences between groups.

289 people were included in the study. The average age was 33 and 82% were male. Most cases were asymptomatic (42%) or mild (40%). People with active substance use disorder reported significantly higher rates of muscle aches and fatigue. 46% were released prior to completing the 10-day isolation period.

Most COVID-19 cases in the jail were mild. Symptoms did not significantly differ in those with concomitant substance use disorder. Most participants were released prior to completing isolation, increasing the risk for community spread

Over 10 million arrests occur per year, and the vast majority of those who are arrested are subsequently jailed in state and county correctional facilities.1 Compared to the general population, people experiencing incarceration are disproportionately burdened by chronic medical problems and are exposed to health risks inherent to incarceration itself, including exacerbations of mental illness due to solitary confinement and increased exposure to communicable diseases.2 In addition, they often have complex healthcare needs given overlapping chronic medical disease, substance use disorders, and mental health disorders and yet due to financial constraints and lack of oversight, medical care provided to people experiencing incarceration often does not meet these complex needs.2 Jails provide ideal conditions for COVID-19 transmission, with high population density, unsanitary conditions, inability to socially distance, and limited health care resources.3 Consequently, transmission rates as high as 5.5 times that of the general population have been reported in some carceral settings.4 One large urban jail reported an estimated reproduction ratio of 8.44, indicating high levels of spread.5 To address this, great efforts have been made to reduce the population in US jails throughout the pandemic with early releases or home confinement.6 Nevertheless, strategies for reducing COVID-19 transmission within jails are critical, with rapid and accurate detection of the disease being a key component.

One factor that can complicate detection of COVID-19 in people who are incarcerated is substance use. Symptoms of withdrawal from substances such as opiates can mimic symptoms of COVID-19 and may be either written off by jail staff or underreported by incarcerated people who do not wish to disclose their substance use. Additionally, given that substance use is often a primary contributor to incarceration, people find themselves dealing with the dual stigmas attached to substance use and crime if they were to disclose their substance use. This problem is compounded by high rates of active substance use among people who are incarcerated, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse estimating a prevalence of around 65%.7 In Minnesota, where this study was performed, the Department of Corrections reported 90% of people incarcerated in their facilities were diagnosed with substance use disorders in 2019.8 This has likely increased further given evidence of rising rates of drug use during the pandemic in the population at large.9

To address the high rates of substance use disorder, jails have instituted medication assisted treatment (MAT) programs which have helped reduce opioid use and increased entry into treatment.10 These have continued during the pandemic with some adaptations, including in our own facility.11 The use of MAT may also affect symptom presentation and therefore detection of COVID-19. Our study aims to describe the presentation and outcomes related to those with COVID-19 and substance use disorder in a large county jail while examining the impact of withdrawal symptoms and buprenorphine administration on detection of COVID-19.

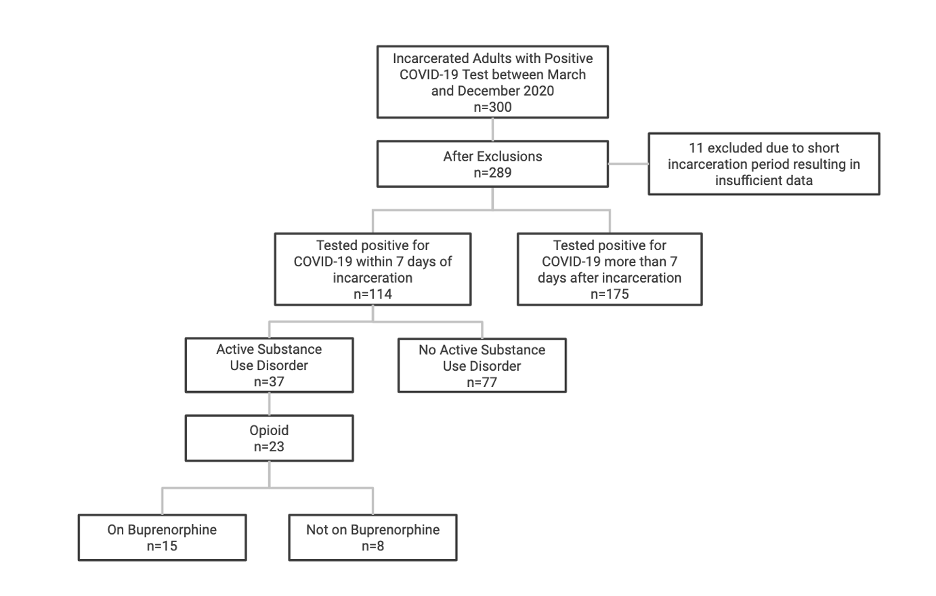

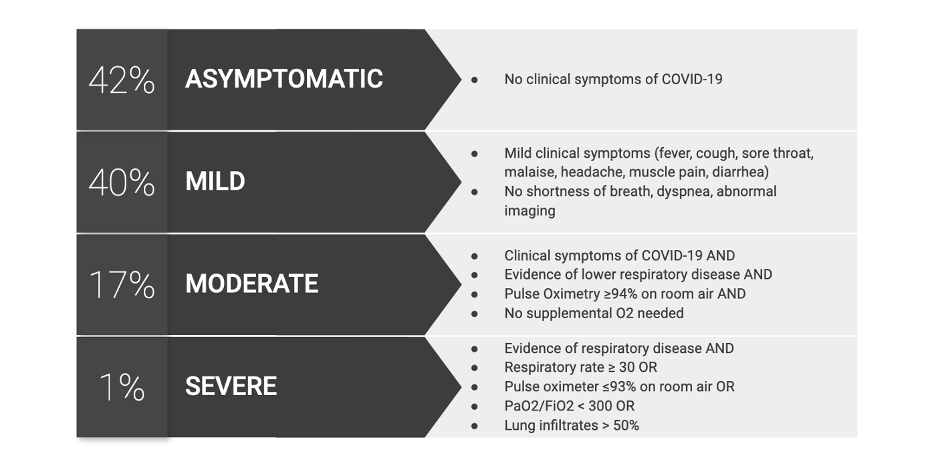

This is a retrospective study of 300 adults who tested positive via PCR for COVID-19 while incarcerated at Hennepin County Adult Detention Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota from March 2020-December 2020. Eleven participants were excluded due to being duplicates or having a very short period of incarceration resulting in no recorded data on substance use or COVID-19 symptoms. Data was collected from the jail electronic medical record (EMR) and included basic demographics like age, sex, and race and ethnicity. We also collected data about the presence of comorbidities that are known to increase the risk for severe COVID-19. Social determinants of health such as homelessness and English language proficiency were collected from a standard intake questionnaire that was uploaded to the EMR. English language proficiency was included to help account for ability to report symptoms and follow directives related to COVID-19 precautions. We collected data related to COVID-19, including number of days from admission to the jail to positive PCR test, symptoms, severity, whether they needed transfer to the ER or admission to the hospital for COVID-19, and whether the participants complete their isolation period in the jail. Symptoms were extracted from standardized daily symptom logs obtained by jail medical staff. Severity was defined according to the NIH disease severity guidelines (Figure 2).

We also collected data related to substance use disorders, including drugs used and last use. These were usually recorded in the intake form or in notes from providers in the jail’s substance use program. Active drug use was defined as having used their drug of choice within one month of incarceration. For individuals with active opioid use, we collected whether they were prescribed buprenorphine after admission to the jail. All data was stored in a REDCap electronic data capture tool provided by the University of Minnesota.12

The participant groups are summarized in Figure 1. For our analysis, we first described the characteristics of all people who tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated. We then reported the symptoms, severity, and course of those who tested positive for COVID-19 within 7 days of becoming incarcerated given the timing of clinical overlap within acute withdrawal. To examine the effect of substance use disorder on presentation, we performed a sub-analysis comparing those with and without active substance use disorder. Within this group we also compared rates of asymptomatic presentation, symptoms only associated with COVID-19 (cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste and smell, sore throat, and fever) and symptoms only associated with withdrawal (chills, fatigue, body aches, headache, congestion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures). Finally, to examine the effect of buprenorphine on symptom presentation, we isolated those with active opioid use disorder and compared the symptoms of those treated with or without buprenorphine.

Analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond WA). Basic descriptive statistics were performed and reported as mean with standard deviation. Two-tailed t-tests and chi-square analysis were used to determine the significance of differences between groups. This project was approved by the sheriff of the jail, overseen by the jail medical director, and approved by the Hennepin Healthcare Human Research Protection Office.

Table 1. Demographics and comorbidities in people who tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated in a large county jail from March to December 2020.

Characteristic | All Patients | |

Age, mean (standard deviation) | 33 (11%) | |

Sex, n (%) | Male | 238 (82%) |

Race, n (%) | African American or Black | 164 (57%) |

White, Non-Hispanic | 42 (15%) | |

American Indian or Alaska Native | 27 (9%) | |

White, Hispanic | 24 (8%) | |

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 8 (3%) | |

Asian | 3 (1%) | |

Homeless, n (%) | 63 (22%) | |

Non-English Speaking, n (%) | 15 (5%) | |

Tobacco Use, n (%) | 168 (58%) | |

No Comorbidities, n (%) | 164 (57%) | |

Comorbidities, n (%) | Hypertension | 58 (20%) |

Asthma | 57 (20%) | |

Diabetes Mellitus | 22 (8%) | |

Obesity | 17 (6%) | |

Chronic Kidney Disease | 11 (4%) | |

Coronary Artery Disease | 5 (2%) | |

History of Substance Use, n (%) | 112 (39%) | |

Substances Used, n (%) | Opioids | 66 (23%) |

Methamphetamines | 49 (17%) | |

Alcohol | 29 (10%) | |

Cocaine | 24 (8%) | |

Substance Use Within 30 Days of Admission, n (%) | 94 (33%) | |

Table 2. Symptoms and outcomes in people who tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated at large county jail with a sub-analysis of those who tested positive within 7 days of becoming incarcerated and who did or did not use illicit substances within 30 days of testing positive for COVID-19.

Characteristic | All Patients n=289 | Active SUD n=37 | Non-SUD n=77 | p-value | |

Symptoms, n (%) | Cough | 92 (32%) | 12 (32%) | 31 (40%) | 0.42 |

Muscle Aches | 86 (30%) | 16 (43%) | 18 (23%) | 0.03* | |

Headache | 79 (27%) | 10 (27%) | 15 (19%) | 0.36 | |

Fever | 38 (13%) | 6 (16%) | 14 (29%) | 0.80 | |

Chills | 60 (21%) | 11 (30%) | 17 (22%) | 0.37 | |

Sore Throat | 63 (22%) | 8 (22%) | 22 (29%) | 0.43 | |

Nasal Congestion | 56 (19%) | 10 (27%) | 16 (21%) | 0.46 | |

Shortness of Breath | 55 (19%) | 10 (27%) | 20 (26%) | 0.90 | |

Loss of Taste or Smell | 55 (19%) | 6 (16%) | 17 (22%) | 0.47 | |

Diarrhea | 35 (12%) | 7 (19%) | 12 (16%) | 0.65 | |

Nausea | 28 (10%) | 7 (19%) | 7 (9%) | 0.13 | |

Fatigue | 17 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0) | 0.01* | |

Vomiting | 12 (4%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (4%) | 0.15 | |

| Mild | 116 (40%) | 14 (38%) | 30 (39%) | 0.91 |

Moderate | 49 (17%) | 10 (27%) | 16 (21%) | 0.46 | |

Severe | 3 (1%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 | |

Asymptomatic | 121 (42%) | 13 (35%) | 31 (40%) | 0.60 | |

Required Transfer to the ER, n (%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1%) | 0.49 | |

Required Admission to the Hospital, n (%) | 3 (0.3%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1%) | 0.49 | |

Isolation Completed in Jail, n (%) | 157 (54%) | 11 (30%) | 11 (14%) | 0.05 | |

Figure 1. Participant selection at large county jail

Figure 2. Classification of severity of COVID-19 disease per NIH disease severity guidelines and corresponding percentage of our participants for each category.

Of the 300 cases initially identified, 289 had sufficient data to be included in the analysis (Figure 1). Basic demographics and comorbidities are summarized in Table 1. The average age was 33 years and 82% were male. The most commonly self-reported race and ethnicities were African American or Black (57%), White non-Hispanic (15%), American Indian or Alaska Native (9%), White Hispanic (8%), and Asian (1%). About one quarter (22%) were identified as experiencing homelessness at the time of incarceration. Five percent had limited English proficiency. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (20%), asthma (20%), diabetes mellitus (8%), obesity (6%), chronic kidney disease (4%), and coronary artery disease (2%). Fifty-eight percent reported using tobacco.

Findings related to COVID-19 status and presentation are summarized in Table 2 with a sub-analysis of patients with and without active substance use disorder and who tested positive for COVID-19 within one week of admission to the jail. 123 cases occurred during an internal outbreak impacting patients at least a week into their jail stay. Given the timing since admission, they were excluded from the substance use analysis. Most cases were asymptomatic (42%) or mild (40%) in severity with 17% having moderate symptoms and 1% qualifying as severe (Figure 2). The most reported symptoms were cough (32%), muscle aches (30%), and headache (27%). Few had vomiting (4%) or fatigue (6%). Fatigue and muscle aches were significantly more common in those with active substance use disorder versus those without active substance use disorder. Ultimately, only 4 patients required transfer to the emergency department for COVID-19 symptoms and 3 were admitted to the hospital for treatment. In all, 54% completed the required 10-day isolation period in jail while the remaining 46% were released prior to completing this period.

As seen in Table 1, 39% percent of all participants had a history of substance use, with the most common substances being opioids (23%), methamphetamines (17%), alcohol (10%), and cocaine (8%). Ninety-four participants (33%) had an active substance use disorder at the time of their incarceration. Of these, 37 were admitted to the jail within 7 days of a positive COVID-19 test which creates potential for overlap of symptoms related to drug use and symptoms from COVID-19. In these patients, we compared the number of participants with withdrawal symptoms (chills, fatigue, body aches, headache, congestion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures) in the group with active substance use versus those did not endorse substance use within 30 days and found that it was not statistically different (p=0.56). The number of participants with symptoms only associated with COVID-19 (cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste and smell, sore throat, and fever) was also not significantly different between these groups (p=0.65). There was also no difference in asymptomatic presentation (p=0.60). Of the 23 participants who were actively using opioids at the time of incarceration and tested positive for COVID-19 within 7 days of incarceration, 15 (65%) were taking buprenorphine while in the jail, which was initiated to treat withdrawal symptoms. There was no difference in the number of participants in these groups with COVID-19 only symptoms (p=0.31).

In this analysis, we summarized the presentation and outcomes of people who tested positive for COVID-19 while incarcerated at a large county jail. We then described the prevalence and type of substance use disorder among this group and the impact of active use and administration of buprenorphine on symptom presentation. We ultimately found no significant differences in prevalence of asymptomatic presentation or specific COVID-19 or withdrawal symptoms between these groups.

Regarding disease severity, our cohort had few moderate and severe cases of COVID-19. This is likely due to a younger population with fewer comorbidities as moderate and severe COVID-19 are more common in people who are 60 years or older or have comorbidities.13,14 Worse outcomes have also been reported in patients with concomitant substance use disorder, although we found no difference in outcomes in our population.15 One explanation for our finding is that our participants’ symptom severity may have peaked after leaving the jail. COVID-19 can take 7 to 10 days to become severe, and many participants were released after only a day or two. In general, incomplete records and rapid turnover in the carceral setting presents a challenge when tracking the clinical course of patients with COVID-19. Nevertheless, fewer reported comorbidities in a younger population, even with comorbid substance use, likely resulted in a lower rate of moderate or severe cases. The prevalence of moderate and severe cases in our facility may change with Delta variant, as some studies have reported increased virulence and transmissibility.16 This may be counteracted with widespread vaccination of this population.17

The most common symptoms were cough, muscle aches, and headaches which is consistent with reported trends.18 Notably, nearly 42% of our population was asymptomatic. While estimates vary widely on the proportion of asymptomatic infections, one study found that in a homeless shelter, which is a similar congregate setting, as many as 87% of infections were asymptomatic.19 Our finding may be explained by a younger and healthier population as well as underreporting of symptoms. There were several instances where participants were unwilling to participate in daily symptom checks. There may also have been incentives to underreport symptoms, such as the perception that this may lead to ending isolation earlier or the desire to hide symptoms of withdrawal. This creates a significant challenge for COVID-19 management in the jail setting, as lack of reporting can lead to decreased detection and isolation, exacerbating outbreaks. These findings support policies that promote testing for COVID-19 in addition to screening for symptoms in the correctional setting.

Another challenge in the management of COVID-19 in the correctional setting is the frequency at which people who are incarcerated continue living in congregate settings when they leave. Twenty percent of our participants reported being homeless at the time of incarceration, which is significant as only 54% completed their isolation in jail. This indicates that some of the people who were released prior to completing their isolation period likely went to a shelter, where the chances of spreading COVID-19 are far greater.20 Others may have gone to other congregate settings like drug treatment centers and halfway houses. This increases the risk for community spread. Given the high transmissibility of COVID-19, it is important for correctional facilities, local public health organizations, and healthcare facilities to collaborate in the care of these individuals. One potential solution is to provide a housing provision for the duration of quarantine for those who are unable to isolate once released.

In this analysis, we also sought to determine if individuals with substance use disorders had a different clinical presentation of COVID-19 than those without active substance use. Many people use drugs immediately prior to incarceration; therefore, it is possible that they had an overlap of withdrawal and COVID-19 symptoms, which complicates using symptom screening alone as a tool for COVID-19 detection. Overall, we did not find a difference in the prevalence of symptoms that are associated with withdrawal compared to COVID-19 alone or the prevalence of asymptomatic presentation between groups, although we were limited by small sample size. In terms of individual symptoms, we found a statistically significant increase in muscle aches and fatigue in those with active substance use disorder compared to those without substance use disorder who were diagnosed with COVID-19, which can be attributed to the overlap with acute withdrawal. Treating withdrawal could reduce this overlap. Overall, our results reinforce the need for widespread testing instead of reliance on symptom reporting for detection of COVID-19.

Our study has several limitations. First, this data was retrospectively extracted from charts which relied heavily on self-reporting and therefore may not represent the true incidence of certain characteristics. It is likely that some people underreported their symptoms due to concerns about being placed in prolonged isolation; additionally there were participants who refused to participate in daily symptom checks on some occasions. It is also possible that errors were made by staff recording the symptoms or taking temperatures. In the future, incentives could be offered to motivate people to participate in symptom checks and staff could be trained on obtaining the information. Additionally, some may not have disclosed their substance use, which could also impact our results. Assuring participants that disclosure will not lead to legal consequences may help mitigate this in the future. It is also likely that some of the participants had undiagnosed or unreported comorbidities. Another limitation was timing. Provided that nearly half of our participants left the jail before their isolation period was over, the lack of reported symptoms may have simply been due to early timing in the course of the illness. A future study could attempt to follow up with participants by phone after they are released. Lastly, our analysis had a small sample size, particularly the groups with active substance use disorder and buprenorphine use. This likely made it difficult to detect a difference between symptom presentation in the patients with and without substance use disorder, increasing the likelihood of a type II error. Future studies should continue to examine the overlap of COVID-19 and substance use in carceral settings to improve detection and care.

We report demographic information, comorbidities, COVID-19 symptoms and severity, and prevalence of substance use disorder in nearly 300 adults incarcerated in a county jail during the pandemic. On average, our population was younger and healthier and therefore had fewer moderate and severe cases and more asymptomatic presentations. Participants with active substance use disorder had significantly higher rates of fatigue and muscle aches compared to those without active substance use disorder. Use of buprenorphine in those with opioid use disorder did not affect symptom presentation. Many of our participants left the jail prior to completing isolation, which may have magnified the spread of COVID-19. This issue was exacerbated by high rates of being unhoused and transfers to chemical dependency treatment programs

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

The Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant support (UL1TR002494 from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences) supported the use of REDCap for this project.

Jillian Wothe is a 4th year medical student at the University of Minnesota.

Jamee Schoephoerster is a 4th year medical student at the University of Minnesota.

Anna Lundeen is a 4th year medical student at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Rachel Silva is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School. She is also a board-certified Internal Medicine physician at Hennepin Healthcare and serves as the Medical Director of the Hennepin County Adult Detention Center. Her advocacy and research centers around incarceration. She received her formal training at Tulane University.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2024 BCPHR: An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal