Oketch E. Medication overload: an overlooked public health burden. HPHR. 2022;47. 10.54111/0001/UU1

Polypharmacy, most commonly defined as the use of five or more medications concurrently, is associated adverse outcomes including increased risk of adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, drug-drug interactions, drug-disease interactions, hospitalizations and mortality (Masnoon et al, 2017; Quinn & Shah, 2017). There is no question that some people, particularly those with multiple chronic illnesses, need several medications in order to limit disease progression, control symptoms, improve function or extend life but excessive polypharmacy (i.e., ≥10 medications) or medication overload is a significant public health concern that is strongly associated with inappropriate medication use (Frank, 2014; Wahab, Nyfort-Hansen, & Kowalski, 2012; Quinn & Shah, 2017). In this paper, the terms medication overload and excessive polypharmacy are used interchangeably to describe the use of multiple drugs that pose a greater risk of harm than benefit with risks here referring to the use of medications that are likely to cause clinically significant drug-disease or drug-drug interactions while benefits referring to the effective management of the disease, delaying a disability outcome, slowing disease progression, and improving patient outcomes with fewer errors, if any (Lown Institute,2020; Quinn & Shah, 2017).

The rising cost of prescription drugs has garnered renewed public attention from patient advocates, private and public payers, prescribers, and policy makers over the past few years (Kirzinger et al., 2019). However, not many people are talking about the growing epidemic of medication overload among Americans which has increased markedly over the last two decades and adds to the cost of prescription drugs, a major category of spending in the U.S health care system (Quinn & Shah, 2017; Maher et al., 2014; Papanicolas et al., 2018). According to Kantor et al. (2015), the prevalence of prescription drug use among Americans aged 20 and older increased from 51 percent to 59 percent between 1999 and 2012 (p<.001), a trend that remained statistically significant even with age adjustment. During this same period, the prevalence of polypharmacy nearly doubled from 8.2 percent to 15 percent. This study findings largely matches similar findings published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017), which found that between 2007 to 2010, almost one-half of the U.S population reported having used one or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days; this prevalence in prescription drug use increased with age due to multimorbidity. This rapid increase in the number of medications people are taking has led to a sharp rise in adverse drug events and if nothing is done, the Lown Institute estimates that adverse drug events related to medication overload will cause nearly 150,000 premature deaths and reduce the quality of life for millions of older Americans over the next decade. In addition, it will lead to 4.6 million hospitalizations and 74 million emergency room and outpatient clinic visits, at a cost of at least $62 billion (Lown Institute, 2020). These numbers represent a staggering impact on patients and induces undue financial burden on health care systems.

Although advances in pharmaceuticals and pharmacotherapeutics has helped people live longer, this increase in life expectancy has caused a shift in the global disease burden with surge in chronic diseases in addition to communicable diseases (Murray & Lopez, 2013). With greater longevity, individuals are at increased risk for poor health outcomes including incident disability, cognitive impairments, falls, and other complex health issues. This co-existence of comorbidities gives rise to the challenge of polypharmacy (Quinn & Shah, 2017). Polypharmacy may be clinically appropriate in many instances but every additional drug increases the risk of harm and therefore it is important to identify patients with excessive polypharmacy that places them at increased risk of adverse events and poor health outcomes (Lown Institute, 2020). Too often, lots of different medications are used in ways that undermine their value or get prescribed for reasons not necessarily supported by evidence or when no clear clinical indication exists (Masnoon et al., 2017). For example, a patient visiting their primary care doctor may be prescribed an antidepressant medication without being aware of or exploring other alternative evidence-based non-drug therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), a form of psychological treatment, that can be effective as, or more effective than the prescribed medication but without the risk of side effects (APA, 2021). Wiechers et al (2013), showed that psychotropic medications get prescribed often without a psychiatric diagnosis or the patient being evaluated by a mental health professional. Often times, these prescriptions add to the patient’s long list of medications already prescribed, herbal or dietary supplements, and over-the-counter medicines that they may also be taking thereby increasing their risk of harm from medication overload (Maher et al., 2014). It is therefore important for prescribers to start incorporating initiatives in their clinical practices to help stem the tide of medication overload and reduce associated health care costs.

There is no single driver of medication overload since many factors contribute to this epidemic (Lown Institute, 2020). Among these are drug-marketing to both doctors and consumers by the drug companies that heavily promotes the benefits of medications while downplaying the risks (usually offered in small-print or fast-spoken), clinical prescribing practices that enable over prescription of unnecessary medications, and the highly fragmented healthcare system that makes it difficult to coordinate care between a patient’s various providers and track all of their medications (Lown Institute, 2020).

As part of the prescribing continuum, interest in a grass-roots movement called “deprescribing” is rapidly gathering momentum in response to increasing levels of medication overload (Reeve et al., 2014; Pike, 2018). Deprescribing refers to a patient-centered process of systematically discontinuing or reducing the dose or frequency of administering medications that have lost their advantage in the risk–benefit trade-off (Reeve et al., 2014; Le Bosquet, et al., 2019). The goal of deprescribing is to improve patient outcomes by minimizing medication overload and reducing the risk of harm or adverse side effects (Reeve et al., 2015).

Health care teams in Australia, Canada and U.K pioneered interest in deprescribing by forming networks – Canadian Deprescribing Network (CaDeN) (https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/), Australian Deprescribing Network (ADeN) (https://www.australiandeprescribingnetwork.com.au/), English Deprescribing Network (EDeN) (https://www.sps.nhs.uk/networks/english-deprescribing-network/) – to counter the blizzard of medication overload and optimize patient care (Le Bosquet, et al., 2019). These networks have developed evidence-based guidelines and tools to help prescribers to deprescribe effectively and safely. The deprescribing initiative is growing in the United States through efforts such as Choosing Wisely campaign, Beers Criteria, STOPP/START criteria, Medication Appropriateness Index and the recently formed US Deprescribing Research Network (USDeN) (https://deprescribingresearch.org/) in an effort to improve patient outcomes by curbing unnecessary drug use (Reeve et al., 2015; Pike, 2018; Le Bosquet, et al., 2019).

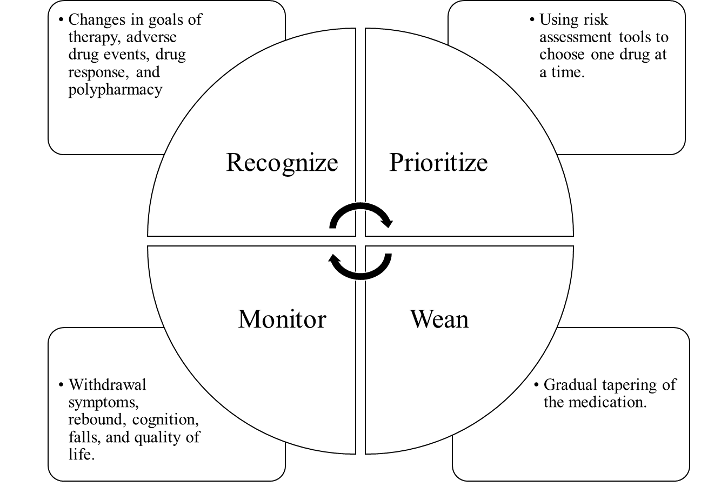

Deprescribing is essential in optimizing patient care. It follows a systematic approach to safely and effectively scale back the dosage or stop a medication and is applicable to prescription medications, over-the-counter medicines, and herbal or dietary supplements (Vasilevskis et al., 2019). The deprescribing approach is based on a conceptual framework that considers identifying a patient’s polypharmacy problems, prioritizing goals of care, and then weaning and monitoring appropriate treatment targets and duration of treatment required for benefit (Figure 1). However, there is no one-size-fits all with this approach. So, it is important that pharmacotherapy needs of each individual patient are assessed and evaluated based on the best available evidence (Reeve et al., 2015).

Medication overload is an urgent public health problem. While significant efforts have been made to address patient medication burden, to date no government agency, public or professional organization has formal responsibility to address this national problem. As with other public health problems, reducing medication overload will require coordinated efforts from different stakeholders. Therefore, it is incumbent upon all stakeholders – individuals, patient advocacy groups, government agencies, clinician specialty groups, and health care institutions – to come together to address and raise awareness about the overlooked public health problem of medication overload.

American Psychological Association (2021). PTSD Clinal Practice Guideline: What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Frank, C. (2014). Deprescribing: a new word to guide medication review. Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ), 186(6), 407–408. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131568

Kantor, E. D., Rehm, C. D., Haas, J. S., Chan, A. T., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2015). Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA, 314(17), 1818-1830.

Kirzinger, A., Muñana, C., Fehr, R., & Rousseau, D. (2019). US Public’s Perspective on Prescription Drug Costs. Jama, 322(15), 1440-1440.

Le Bosquet, K., Barnett, N., & Minshull, J. (2019). Deprescribing: Practical Ways to Support Person-Centred, Evidence-Based Deprescribing. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland), 7(3), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030129

Lichtenberg, F. R. (2014). The Impact of Pharmaceutical Innovation on Disability Days and the Use of Medical Services in the United States, 1997–2010. Journal of Human Capital, 8(4), 432–480. https://doi.org/10.1086/679110

Maher, R. L., Hanlon, J., & Hajjar, E. R. (2014). Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert opinion on drug safety, 13(1), 57-65.

Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L., & Caughey, G. E. (2017). What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 230.

Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. (2013). Measuring the Global Burden of Disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 369(5), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1201534

Papanicolas, I., Woskie, L. R., & Jha, A. K. (2018). Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA, 319(10), 1024-1039.

Pike, H. (2018). Deprescribing: the fightback against polypharmacy has begun. Pharmaceutical Journal, 301, 11.

Quinn, K. J., & Shah, N. H. (2017). A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Scientific Data, 4, 170167.

Reeve, E., Gnjidic, D., Long, J., & Hilmer, S. (2015). A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 80(6), 1254-1268.

Reeve, E., Shakib, S., Hendrix, I., Roberts, M., & Wiese, M. (2014). Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence‐based, patient‐centred deprescribing process. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 78(4), 738–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12386

Saini, V., Garcia-Armesto, S., Klemperer, D., Paris, V., Elshaug, A. G., Brownlee, S., … & Fisher, E. S. (2017). Drivers of poor medical care. The Lancet, 390(10090), 178-190.

Vasilevskis, E. E., Shah, A. S., Hollingsworth, E. K., Shotwell, M. S., Mixon, A. S., Bell, S. P., … & Simmons, S. F. (2019). A patient-centered deprescribing intervention for hospitalized older patients with polypharmacy: rationale and design of the Shed-MEDS randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 165.

Wahab, M. S. A., Nyfort-Hansen, K., & Kowalski, S. R. (2012). Inappropriate prescribing in hospitalised Australian elderly as determined by the STOPP criteria. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 34(6), 855–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9681-8

Wiechers, I. R., Leslie, D. L., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2013). Prescribing of Psychotropic Medications to Patients Without a Psychiatric Diagnosis. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 64(12), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200557

Working Group on Medication Overload. (January 2020). Eliminating Medication Overload: A National Action Plan. Brookline, MA: Lown Institute; 2020.

American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. (2019). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(4), 674–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

Fick, D. M., Semla, T. P., Steinman, M., Beizer, J., Brandt, N., Dombrowski, R., DuBeau, C. E., Pezzullo, L., Epplin, J. J., Flanagan, N., Morden, E., Hanlon, J., Hollmann, P., Laird, R., Linnebur, S., & Sandhu, S. (2019). American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 67(4), 674–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

Hanlon, J. T., & Schmader, K. E. (2013). The Medication Appropriateness Index at 20: Where It Started, Where It Has Been, and Where It May Be Going. Drugs & Aging, 30(11), 893–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0118-4

Levinson, W., Born, K., & Wolfson, D. (2018). Choosing Wisely Campaigns: A Work in Progress. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 319(19), 1975–1976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2202

O’Mahony, D., O’Sullivan, D., Byrne, S., O’Connor, M. N., Ryan, C., & Gallagher, P. (2015). STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age and Ageing, 44(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu145

Ednner Oketch is a public health professional at the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. She holds a Master of Science in Health Systems Management from the University of Baltimore and a Master of Public Health with a concentration in global health from George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health.

Her research interests are focused on the intersection of public health interventions and medication safety and use in vulnerable populations, monitoring and evaluation, global health systems development, and global health equity. In 2019, she was named the recipient of the Dean’s Spirit Award for exemplify the spirit of the School of Pharmacy by promoting a healthy school community.

Ms. Oketch is currently completing an internship with the Biomedical Prevention Branch within USAID’s Office of HIV/AIDS, Prevention, Care and Treatment Division and is an incoming Fellow with the Science and Program Office within CDC’s Center for Global Health, Global Immunization Division.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2024 BCPHR: An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal