Golden A, Solis L, Yousefian F. Augmenting LGBTQ+ and minority identities within medical school and residency training. HPHR. 2021;42. DOI:10.54111/0001/PP4

Medical training is a lengthy process that requires mental, physical, and emotional prowess. It is a costly journey, but an ultimately rewarding one for those who want to become a physician. Many people sacrifice several aspects of their life to receive their DO or MD, thus complicating the journey is something most hope to avoid. However, personal identity is increasingly becoming a sacrifice that minorities have to make to pursue a medical degree. While society has seen a substantial increase in awareness and acceptance of minority groups over the last few years, the medical community can do their part in augmenting this growth by helping these populations feel comfortable embarking on the journey to become a physician. While medical institutions may have foundational policies regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), there still seems to exist a disparity among the physician workforce. By identifying barriers within the medical profession for minority groups and modeling recruitment, applications, and interviews after programs that are paving the way for a more inclusive profession, medicine will become a safer, more equitable field.

Applying to medical school and residency are life-altering events. Applicants sacrifice a significant portion of their lives to become a DO or an MD physician. Requiring four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school, and anywhere from three to five-plus years of residency (excluding a fellowship), applicants spend over a decade of their lives within the higher education system training to become physicians. The process, though mentally, physically, and financially taxing, has myriad benefits to the community and nation at large. Thus, avoiding unnecessary complications while pursuing a medical degree is understandably a top priority for those who choose this career path. However, applicants have often been faced with the misfortune of having to sacrifice parts of their identity to be accepted in the medical community.1 Of note, the aforementioned sacrifice does not come from the stress of the work itself, but rather from the overarching structural insecurity, social marginalization, and racial exploitation that challenges our applicants to comply to the present standards.1 While society has seen a substantial increase in awareness and acceptance of minority groups over the last few years, the medical community can do their part in augmenting this growth by helping these populations feel comfortable embarking on the journey to become a physician. Thus, a gradual increase in the number of minorities practicing medicine can be an apparatus to address health disparity and leave lasting impressions on minority groups across the nation. While medical institutions may have foundational policies regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), there still seems to exist a disparity among the physician workforce (Table 1). Researchers found that physicians from minority backgrounds were more likely to care for patients from vulnerable populations.2 Therefore, the compelling evidence suggesting that increasing racial and ethnic minorities as physicians results in improved patient trust and satisfaction, provider-patient relationship, and cultural competency is of no surprise.3 As a result, the disparities affecting underrepresented minority patient populations are addressed more compassionately with the physicians who identify as minorities themselves with better patient care.3 As illustrated in Table 1, the medical community needs to diversify their workforce more than ever by implementing strategies to represent our diverse patient population in the United States.

Medical School: MD 2021-2022 | Medical School: DO 2021-2022 | Residency: MD 2020-2021 | Residency: DO 2020-2021 | Practicing Physicians: MD + DO 2019* *reported every 3 yrs | ||

White | 51.50% | 56.70% | 50.00% | 67.50% | 56.20% | |

American Indian/ Native American | 1.00% | 0.20% | 0.60% | 0.60% | 0.30% | |

Asian | 26.50% | 24.40% | 21.80% | 19.80% | 17.10% | |

African American/ Black | 11.30% | 3.30% | 5.80% | 2.50% | 5.00% | |

Hispanic/ Latino/ Spanish | 12.70% | 7.50% | 7.80% | 4.30% | 5.80% | |

Pacific Islander/ Native Hawaiian | 0.40% | 0.10% | 0.20% | 0.20% | 1.00% | |

Table 1. Race and Demographics of Medical Students, Residents, and Practicing Physicians in the USA4–

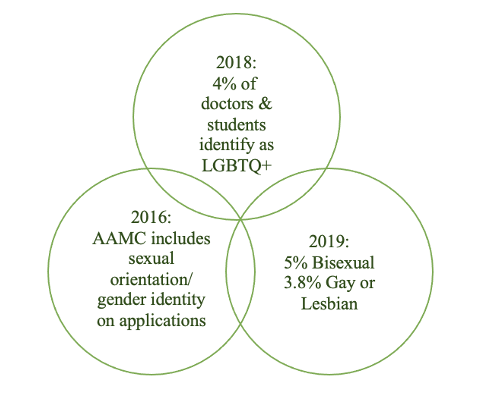

A large part of the disparity described above, both historically and recently, is a combination of economic burden, time, and travel restrictions associated with COVID-19.6 Moreover, personal identity identity, which expands beyond race and ethnicity, has been a critical source of this disparity as well.1 Other identifiers such as religion, culture, sexual identity, and gender identity play a big role in the lives of many future and current doctors. Neglecting these identifiers or making people feel the need to hide them from others has real world consequences.1 For example, members of the LGBTQ+ community often feel the need to conceal their identities in order to avoid discrimination.7 It has been reported that LGBTQ+ medical students and physicians are far more likely to endure injustice and burnout compared to their heterosexual counterparts.7 In addition, over 50% of transgender/nonbinary residents did not feel safe discussing their identity, and 40% were misgendered during their interviews.7 In a profession that vows to do no harm and advocate for the safety of patients, those within admissions for medical education can learn from programs around them regarding recommendations for enhancing diversity within the medical field.

Figure 1. Recent LGBTQ+ Statistics from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)8

All governing bodies of medical institutions have policies regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). For instance, the ACGME explicitly notes that residency programs must implement policies and procedures regarding the recruitment and retention of underrepresented minorities in medicine.9 They also require an annual evaluation from each residency program that includes a specific section indicating the endeavors the program took to uphold diversity at their institution.9 While some programs excel in diversifying their workforce, other programs fall short, likely due to a foundational error hidden behind implicit biases. These unconscious attitudes spill out into our everyday lives and can affect not only our personal experiences but our work outcomes as well.10 Nevertheless, there have been recommendations from other institutions on how this problem can be rectified, as seen in this article, and extrapolated to any level of medical education.

One approach to achieving successful outcomes in the realm of diversity is to focus on faculty. A helpful technique is bridging the gap between tenured and newer faculty at medical institutions.11 If senior faculty are open to mentorship, their younger colleagues will be more inclined to share sensitive, constructive criticisms stemming from the foundation of a program.11 Subsequently, they will want to offer solutions to them as well.11 Additionally, senior faculty members, especially those who identify as underrepresented minorities, can work together across institutions to guarantee that faculty development programs are geared toward diversity while simultaneously breaking down the systemic barriers that allow these injustices to prosper.11 Overall, a faculty-centered approach can have promising outcomes if safe spaces are created at medical institutions that are intentionally seeking equity.

Furthermore, the age of COVID-19 revealed ways we can improve application cycles in favor of diversifying physician demographics. Hosting virtual information sessions is one way to do this. Virtual settings remove the economic burden of traveling to programs of interest while elevating the opportunity for financially troubled applicants to network.6 The American Psychiatric Association’s Black Caucus enjoyed their success during the application cycle, hosting 107 medical students and thirty-six residency programs.6 Of those 107 participants, ninety of them expressed a new interest in a program they had not considered before.6 Moreover, equity can be achieved by simply offering virtual or hybrid experiences for applicants.6 Hopefully, as we progress into a post-pandemic era, we can maintain virtual opportunities for medical applicants at every level of training.

Regarding the content and course of the applications and interviews themselves, there are several ways to make them more inclusive. One simple change is allowing applicants the opportunity to write in their sexual identity and pronouns on applications and at interviews rather than only having binary options.7 Another way to be more inclusive is by providing specific socials or opportunities for connection with current students and faculty who share aspects of identity.7 In a similar fashion, programs could adopt their own version of the LGBTQ Applicant Resident Chat implemented at Massachusetts General Hospital. These chats provide confidential opportunities, for applicants who opt-in, to explore how inclusive the program is from an intern’s perspective.13 They felt that by providing this option to their resident applicants, they are providing an efficient, safe way for their residency classes to match the population of patients served in the USA.13 Programs might also provide a list of organizations in their area that support the community, such as a variety of places of worship. This could help applicants feel a sense of belonging in their programs of interest.7 Moreover, program leadership can demonstrate support for diversity by serving on boards of directors for DEI-focused organizations with which they interact. For example, Boston Medical Center’s general surgery residency program recommends having someone from a sponsoring residency program assume a role in the Human Right Campaign’s Health Equity Index, which aims to gauge how healthcare facilities treat LGBTQ+ patients.13 Finally, residency programs and medical schools need to incorporate structural racism training and discussions into their interview process so all applicants can receive equitable consideration.9 Though these are only a few recommendations, they have the potential to make huge impacts in benefitting minority populations. Those with minority identities want to see programs outwardly supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Having these kinds of actionable items as part of protocol within medical training can help applicants feel both comfortable and accepted by the programs they apply to.

Representing the medical profession at all levels of training is an honor and a privilege. While the melting pot that is in the United States includes many diverse backgrounds and cultures, there is a lack of representation of this diversity amongst practicing physicians. Though this has been the trend since medicine’s inception, medical schools and residency programs, as well as hospitals across the nation, can help ensure that evolution is happening in the name of diversity. By identifying barriers within the medical profession for minority groups and modeling recruitment, applications, and interviews after programs that are paving the way for a more inclusive profession, medicine will become a safer, more equitable field.

Alexander Golden is a third-year medical student at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine (UIWSOM) in San Antonio, TX. He graduated with a B.A. in Spanish from Rutgers University and an M.S. in Biomedical Sciences from Texas A&M University before matriculating into medical school. He currently serves as the National Diversity Chair for the Council of Osteopathic Student Government Presidents (COSGP) and Phase II Leadership of UIWSOM’s Student Government Association.

Dr. Solis is an Assistant Professor of Applied Humanities and the Assistant Director of the Master of Biomedical Science Program at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine. She completed her doctoral program in Leadership Studies at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, focusing her research on how leaders communicate. She serves as a chair for the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine’s Council on Diversity and Equity and a co-chair for UIWSOM’s Anti-Racist Transformation in Medical Education.

Faraz Yousefian is a clinical dermatology research fellow and sub-investigator at the Center for Clinical and Cosmetic Research, Aventura, FL. He is currently sub-investigating and conducting a variety of private or publicly funded phase I-III clinical trials. He received his Doctor of Osteopathic at the University of Incarnate Word and completed his medicine internship at the Texas Institute for Graduate Medical Education and Research (TIGMER).

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.