Rafina is a town in Attica, Greece and home to 13,000 residents, though the population swells to 50,000 in the summer.1,2 To the west, across a national road lie the Penteli mountains, a hilly wooded area.3 Rafina can be accessed by 3 national roads, as well as by ferries to the nearby islands. A smaller village, Mati, sits just north of Rafina andis a popular tourist destination.4 (figures 1 and 2.) The coast of Attica faces challenges with illegal buildings. Waves of immigration following World War I and the Greco-Turkish War landed many new residents in Athens and the surrounding coast, where they settled in ‘afthereta’, or unauthorized developments on lands that do not follow safety regulations.5,6 In Mati, this led to narrow roads with few exit points throughout the village.7,8 Few roads are wide enough to allow for large movement of traffic or people.

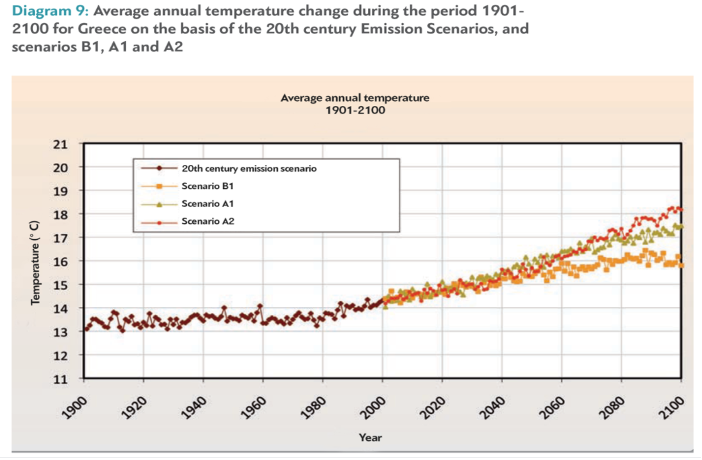

Typical Mediterranean summers are hot and dry. Annual temperatures in Greece have been rising since the 1980s, leading to longer, drier summers in recent years (figure 3).9,10 Although the overall 2018 season was mild, the day of the wildfires was the hottest recorded that summer, with low precipitation.8,11 Wind gusts on the day of the fires were upwards of 56 km per hour, the highest on record in the area since 2010 (figure 4.)8,11

At 12:03, a fire erupted on the opposite coast of Attica (Figure 5). The fire service dispatched a large ground and aerial team to combat the flames.8,13 At 16:41, a separate fire broke out on Mount Penteli.8,13 35 minutes later, flames 3.5 kilometers in length moved eastward.8,13 Fire services were made aware of the new flame at 16:57 and 24 vehicles were dispatched from the opposite coast to reach Rafina.14

At 17:21, flames 6 kilometers in length reached the village across the national road from Rafina, gaining in speed.8 By the time it reached the settlement, the fire was 1 kilometer in length.8,14 Because there was no alarm system in place, residents and tourists had no advance warnings and were rapidly beset by flames.8 At 18:30, less than two hours from when the wildfire first broke out, it had reached the seaside.8,13

The haphazard layout of the town, thick smoke, and speed of the fire’s spread hindered residents fleeing.8,15,16 Because there were no official warnings, some families delayed in evacuating; this decision proved fatal for many who became trapped, perishing in their homes.8,15,17 Residents fleeing on foot were quickly lost in the smoke-filled maze of streets; those who fled in cars found themselves trapped in traffic in the few roads heading away from the area.8,15,18 Some victims were found burned in their vehicles in the aftermath.16 Others fled on foot towards the sea, but were overtaken by the flames and smoke.

Access to beaches was difficult due to the steep slopes covering much of the coastline; the seaside was also thickly settled; long stretches of buildings were stacked against each other with only a few narrow routes between them to access the waterside (figure 6.)24 Those who reached the beaches were forced into the water by the suffocating smoke (figure 7-9). While some were rescued by nearby fishing boats, others drowned.8,19 The coast guard and fishing ships ultimately rescued nearly 700 people from the ocean.20 Heavy traffic on the roads into Mati delayed firefighters attempting to reach the area.18,19 News reports from the days following the wildfire noted that the airfleet struggled to contain the blaze due to strong winds.21

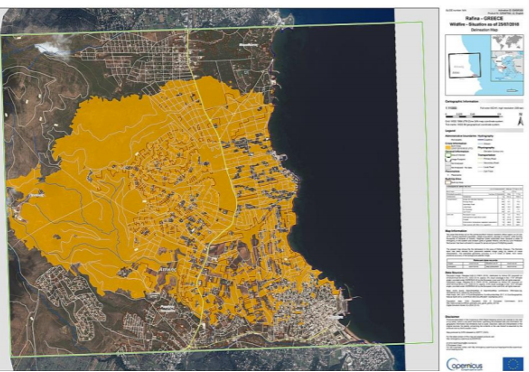

When the flames were finally controlled, the vast majority of buildings in Rafina and Mati were damaged (figure 10).22,23 The fire had ravaged over 3000 homes, leaving hundreds of locals to take shelter in vacant hotels, a summer camp and a nearby army center.22,24 Over 100 people lost their lives.24,25 Roughly half of those who died were aged 60 or greater, due to difficulty these individuals had evacuating their homes quickly, given the speed with which the fire spread.25 Eleven children perished in the flames.25 The vast majority of victims were Greeks; 4 tourists also died.25 The youngest victim was a 6-month old infant who died of smoke inhalation as his mother attempted to reach the sea.18,19 Nearly 200 individuals were injured, many requiring intensive care.

Survivors suffered from burns and complications due to smoke inhalation as well as eye irritation, emotional distress and shock, and exacerbations of underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and asthma.24

What made this fire so deadly? In a broader sense, the 2018 wildfires cannot be considered outside of the context of climate change and its effects on the Mediterranean basin. Rising temperatures have been documented in the region since the second half of the 20thcentury (figure 3), and are known to be associated with more extreme weather events such as wildfires.11,26 There has been a global trend of increasing intensity and frequency of wildfires in recent years, exacerbated by rising temperatures and prolonged dry season.26 Sustained hot temperatures in the Northern hemisphere that could virtually not have occurred in the absence of anthropogenic climate change contributed to this alarming trend the summer of 2018, which also saw record-breaking temperatures in North America and Asia.26,27

Anthropogenic climate change also influences drought patterns, another strong risk factor for intense wildfires. Prolonged dry seasons increase the availability of burnable fuels for wildfires, making them stronger and more deadly.26,28 Studies have also shown patterns of a wet season with higher precipitation coupled with prolonged drought to be a particularly dangerous combination, as rains allow for more growth of plants that subsequently die and dry out during the drought period, increasing burnable biomass available to strengthen and spread flames.28 Pine trees and evergreen shrubs provide ample fuel for wildfires and are naturally adapted to endure them as part of their normal life cycle.29 But coupled with intense winds and high temperatures, this increased fuel availability in the wildland-urban interface on mainland Greece yielded favorable conditions for the flames to grow in size and intensity and move at breakneck speeds that many could not outrun.

While meteorologic conditions combined with high burnable fuel availability in the area certainly contributed to the widespread destruction the 2018 wildfires left behind, they cannot fully explain the extent of mortality seen. Wildfires are a naturally occurring phenomenon in much of the Mediterranean; while climate change may increase the frequency and intensity of wildfires in the forests of the Mediterranean, these events are not always this deadly (figure 11.)17 Other factors need to be considered in the case of the wildfires that ravaged the coast of Attica in 2018.

In reviewing official documents, news and research publications, and expert and public opinions on the events of the 2018 Attika wildfire, several common themes arose: first, illegal buildings leading to easily destroyed homes and few escape routes in the village; second, underfunded government institutions contributed to outdated and ineffective fire-fighting equipment and inadequate forest and land management. Third, poor emergency preparedness planning led to chaos when the fire reached the villages. Finally, lack of coordination between the relevant parties responding to the disaster meant the fire could not be addressed effectively, leading to unnecessary loss of life.30

As mandated by Greek parliament, a panel of experts on wildfires, forest management, and emergency response was assembled to draft a report seeking to explore the system failures that contributed to the high mortality associated with this disaster. Published in the spring of 2019, the report highlights how Greece’s loosely coupled and fragmented systems were further weakened by lack of funding, poor coordination, absence of emergency planning on national, district and local levels, and illegal land development, contributing to the high mortality seen in Rafina on July 23rd, 2018.8,17

Greece has long had a spatial planning problem. As the Greek population flocked to cities in the last century, illegal building became common in both urban and rural environments.6 In this context, afthereta led to two major problems: first, illegally constructed buildings did not follow any regulatory codes and were often composed of poor quality, highly flammable materials compared to legally built structures.17,18 This ultimately led to severe damage to both towns due to the wildfires; 95% of buildings in the area were damaged, leaving hundreds of residents homeless.22-24

Secondly, these afthereta were constructed haphazardly, with no consideration into the layout of homes.18 Many homes were constructed directly along the coast due to the desirability of sea-front properties; with structures surrounded by walls crowding the coastline, residents had few routes available to them to access the sea and escape.18,31 This access was even further limited by the cliffs lining the coast. This is just one example of how the haphazard layout throughout the village led to high mortality, as residents struggled to find the few escape routes left among the town’s maze of winding streets and the wall of illegally-built houses along the coastline.18,32

Little had been done prior to the wildfires to address illegal buildings. In some ways, the Greek government has been not only tolerant but permissive of the culture of afthereta, building roads to facilitate access to illegal structures instead of issuing citations.18 Rather than tackle the problem of disorganized spatial planning brought on by these illegal buildings, the Greek government, based on actions in recent years, seems to condone these activities. For example, in 2017, a bill was proposed to legalize afthereta across Greece, despite the dangers exemplified by the wildfires of allowing many of these structures to stay standing.18

Another problem created by poor spatial planning manifested itself in areas of the village further from the coast. In the hills, where houses sat up against Attica’s pine forests with no tracts keeping the areas separate, the wildland-urban interface allowed for the rapid growth and spread of fire.17 Here, too, illegally constructed buildings led to unregulated wildland-urban interface; excessive development can lead even small fires to become large and deadly.17 Furthermore, poor forest and rural land management practices left burnable fuels in close proximity to a number of rural houses. In the 1960s and 70s, as the economy shifted away from agrarian work and towards the tourism industry, many Greeks abandoned homesteads for more lucrative work metropolitan areas.17,32

The outcome of this migration is that many rural areas and farmland are no longer being kept up and cleared of grasses and biomass as elderly residents retired and younger generations moved away from their villages.17,28,29 While olive trees are difficult to burn when well maintained, abandoned groves with grass accumulation at the foot of the trees provide ample fuel for forest fires. Moreover, the infrastructure for forest management in Greece had been underfunded and weak for years, a situation that was only made worse by austerity measures imposed after the financial crisis; the forestry service was severely underfunded and had no management plan for prevention of wildfires at the time of the 2018 wildfires.17

The lack of planning and inadequate resource allocation for fire prevention and management in the forestry service is just one example of a trend of poor preparation for fire-related disasters across multiple government institutions. At the highest level, the various institutions charged with fighting fires in Greece are both underfunded and poorly organized into isolated silos, leading to communication issues and operational challenges.17 At the local level, emergency preparedness planning and civilian awareness is virtually non-existent. In Attica, a region well known to be fire-prone, this combination proved especially deadly during the wildfires on July 23rd.

Funding for fire-fighting in Greece adds another layer to the system failures; underfunding is reflected in the outdated fleet of fire-fighting vehicles, many of which are badly in need of repair or replacement altogether.17,18 Fire-fighters are tasked with purchasing their own protective equipment, much of which is also outdated and inadequate when tackling intense wildfire flames, and the department itself has seen budgets slashed in recent years due to austerity measures in the face of Greece’s economic crisis.18 While the 1990s saw an increase in money funneled into fire services through the purchase of a fleet of aircraft, much of the fleet now sits in disrepair and is unusable.17 Many of the aircraft were grounded at the time of the July 23rd fires due to prohibitive repair costs, and those that were operational experienced delays in reaching the area.18 The causes of these delays are at this time still under investigation, although some sources remark on aircraft being grounded due to the high winds.33,34 Ground vehicles, too, are badly in need of repair; two thirds of firefighting trucks were out of service at the time of the fires.18

Another major finding of the 2019 official government report on the fires was that the national budget to tackle fires in Greece primarily funnels funding into suppressive measures, leaving fire prevention underfunded. While a major contributor to wildfires in Greece is the accumulation of biomass in poorly managed agricultural lands and forests, no fuel management plan existed in the national fire plan at the time of the tragedy.17 And while laws are in place to delegate authorities to implement evacuation and preparedness plans for land clearing and fuel reduction, the lack of funding available for these activities leaves many of these plans unexecuted.17

Fire suppression services are provided by six ministries, among them the fire service, forest management service, offices of civil protection, local authorities, and police and military forces, which must communicate and coordinate to provide effective responses in the event of wildfires. These organizations must work cohesively to execute the tasks involved in fire suppression. Communication among these ministries is poor; no organized system exists for the exchange of information among the bodies tasked with creating the national fire plan.17

Honing into the events on the day of July 23rd, it becomes clear how these organizational features led to a piecemeal and inadequate response to the fires. In addition to the rapid growth of flames and lack of adequate funds for fighting fires, the villages themselves had no plan for notifying or evacuating citizens in the event of fire.17 Worse, some of the earliest police responders at the scene guided vehicles back to Mati towards the flames, thinking the national road would halt the spread of the fire. Their actions instead exacerbated an already dangerous situation.18

Even after officials were notified of the severity of the wildfires in the area, much of the response was delayed. Survivors who escaped the flames by crowding on the beaches describe waiting hours for the coastguard to arrive. Of those who were forced into the water, many were picked up by local fishing boats while waiting for help to arrive, while others perished in the sea.18 Worse, the coastguard failed to alert incoming ferries from the nearby islands of the situation. In the same time that residents and visitors of Mati waited to be rescued, scores of tourists and cars from the islands were deposited into the chaos and congested roads, further hampering the process of evacuation.18

Wildfires have been a natural phenomenon for centuries, but their impact on humans has worsened in recent years.26 Moving forward, Greece will have to reconcile exploitation of natural resources with the long-term fallout of continued pressure on its natural systems. But why, in the wildfires of Attica in the summer of 2018, did so many lose their lives? The system and governance failures that culminated in the loss of 102 lives and the better part of two seaside towns have yet to be addressed in any meaningful way. The trend of internal migration from rural areas into the city continues in Greece. These population shifts in turn continue to put pressure on the ecosystems that interface with developed areas, with no regulatory body to oversee spatial planning and no preventive measures to reduce the fuel accumulation in forests and abandoned farmlands.17,29 To date no national or local fire emergency preparedness plans exist. The focus remains on suppressive efforts over wildfire prevention strategies.17

The institutions charged with fighting fires in Greece remain underfunded and siloed, poorly coordinated and yet to establish a cohesive strategy to tackle wildfires in an organized fashion. Firefighters continue to perform their duties despite inadequate equipment and salary cuts. Public concern over the threat of wildfires has waned again as Covid-19 swept across the globe drawing attention away to a more visible threat. The system as it stands is not sustainable and will only result in another catastrophe when the conditions are perfect again.

To date, little more has been done to rectify the flaws in Greece’s approach to firefighting. As recently as November 2020, parliament has introduced legislation for the legalization of afthereta, a step backwards in addressing future fire disasters.35 As long as such actions continue to be prioritized over more sustainable measures, history will repeat itself.

One year after the wildfires, Mati still sits in ruin, much of the debris from the tragedy yet to be cleared. Masses of burned branches and rubble have been gathered together and left on a plot of land, waiting to be collected and processed.22 It is only a matter of time before conditions align again to create another devastating wildfire.

![]()