Wieschhaus K, Blair A, Garcia L, Poonawalla M. An experiential student-run curriculum addressing the health outcomes of formerly incarcerated people. HPHR. 2021; 30.

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD32

It is well known by any student of medicine that certain racial, socioeconomic, and demographic groups are more inclined to particular disease states and causes of morbidity and mortality than are others. For instance, a second year medical student could tell you that African Americans are 20% more likely to die from heart disease than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.3 A novice first-year student may even have the capability to inform others of the well-documented increased likelihood of Hispanic and Latino Americans being affected by diabetes as compared to non-Hispanic white and black Americans.4

Moving up the ladder, a senior medical student could more than likely articulate that, on the whole, Asians are a relatively low-risk group for a majority of comorbidities, unless we are discussing Hepatitis B, liver cancer, or tuberculosis, in which case they are at an elevated risk relative to other minority groups.5 Further, it would not be uncommon for a junior resident to be well-versed in the many facets of how low socioeconomic status is associated with substantial reductions in life expectancy across the globe.6 But, after all of these years of undergraduate and graduate medical education, how many of the aforementioned trainees could correctly describe the largest barriers to adequate health care are for formerly incarcerated persons (FIPs)? Could they tell you a single fact about what access to care looks like after release from prison? Or which specific mental health diseases are of particular concern post-incarceration?

Short of a full-time correctional medicine attending, very few clinicians have been trained in the care of FIPs, despite the fact that as of 2013 the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world at 716 per 100,000 individuals7, and more recent data in 2020 is showing that 0.7% of the US population is currently in federal prison, state prison, or local jail.12 To put it into context, the USA only represents a little over four percent of the world’s population, but we house over 20% of the world’s prisoners.7 As our incarceration rate continues to rise, so does the rate of FIPs, requiring not only access to healthcare, but access to healthcare from clinicians to their unique healthcare needs.

It is known that FIPs face a disproportionate risk of death and serious illness in the immediate post-release period. Therefore, this is a critical time to initiate community-based care for chronic illnesses and behavioral disorders.1 At the same time, although, most medical students will go through an entire 4-year curriculum without ever understanding how care for this population should differ, what this disparity looks like, or even why this gap exists. In fact, very few schools have even attempted to bridge this gap in comprehensive health care education.2 Among the schools that have made an effort, pilot studies have found that students’ experiences in this setting have been positive. What remains lacking though, is represented by students’ requests for a more structured curriculum and more opportunities to develop content understanding of the unique clinical aspects that surround prison-related health care.2

In an attempt to answer this organic request, several schools have begun rolling out student-run programs to fill the aforementioned void in medical education. Fresh Start is among these student-run programs, hosted at the Community Health Center in Chicago, IL, and is dedicated to preventing/managing chronic disease and promoting community wellness by emphasizing health education. This program does weekly health presentations in both English and Spanish regarding physical activity, nutrition, and lifestyle changes targeted toward the formerly incarcerated population. It also offers one-on-one health counseling where healthy goals can be made addressing participant’s physical wellbeing in addition to their mental health and psychological needs. Various basic health metrics are also recorded weekly, including height, weight, BMI, and blood pressure, to allow for objective tracking of progress meant to supplement and motivate in parallel to their primary medical care, not replace it.

Student-run programs such as Fresh Start have been well-received by medical students across the country, along with their schools and communities, with over 50% of schools in one study reporting to have something of this nature at their institution, but not specific to the formerly incarcerated population.8 Of the respondent schools, these programs were frequently cited as largely important not only for supplementing patient care, but also for the medical education of participating students.8 They have also opened the door for more widespread integration of correctional medicine concepts into the meshwork of medical school, if a focus were to be placed on this population.

Participation in a hands-on program, without being coupled with any foundational background knowledge, however, does not adequately address the matter at hand – a lack of focused attention on the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated populations as it pertains to health outcomes. “Adequate” education, when defined legally, has 2 basic components – (1) educational quality of experience and (2) creation of a functional system containing all necessary tools and resources to deliver said “quality”.9 A fusion of didactic, evidence-based foundational knowledge, practical experience, and repetition to ensure retention are all needed to meet these minimum standards of educational adequacy; hence, a curriculum that can provide the system that ultimately allows for quality.

The purpose of this study was not just to create a syllabus, but rather, to begin a dialogue surrounding focused health care education targeting the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated demographic of patients, with hopes of identifying an effective curricular design. We postulate that this can be accomplished through practical experience provided by the counseling program Fresh Start offers, combined with a physician led, article-based discussion regarding this particular population, all capped by a lecture from a practicing correctional medicine physician. Our goal is to illustrate that the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of medical students regarding the formerly incarcerated population can be improved by this simple curriculum.

Method

This was a single-center, unfunded, cohort survey study approved by the Loyola University Medical Center internal review board (IRB) and conducted between the years of 2018-2020.

The primary outcome of this study is a shift in medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes – as assessed by pre/post MCQ testing and surveying – surrounding formerly incarcerated persons. Big picture, this is a first step in addressing a healthcare disparity ultimately aiming to improve healthcare for the above-mentioned population.

The target population of study included volunteer medical students, M1 through M4, at Loyola University Chicago – Stritch School of Medicine (SSOM). Thirty-four students across all 4 training levels participated in the study and completed the curriculum, and 9 students completed the entirety of follow-up testing and surveying.. The lowest amount of risk was afforded to those we surveyed, as the collection was anonymous. Inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found below

Inclusion:

Exclusion:

A survey tool, assessing medical students’ perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge regarding the formerly incarcerated population and their health status, was used as the primary means of evaluation. The survey (see attached at end) was distributed to students before they began the proposed curriculum to assess their initial thoughts on what factors they believe, if any, affect the health of the formerly incarcerated population as well as assess their skills pertaining to/knowledge of the population. After the students completed an article-based curriculum and then attended a presentation hosted by our physician mentor and students who completed the correctional medicine elective rotation, we again administered the survey to assess students’ change in their attitudes and knowledge regarding this specific population.

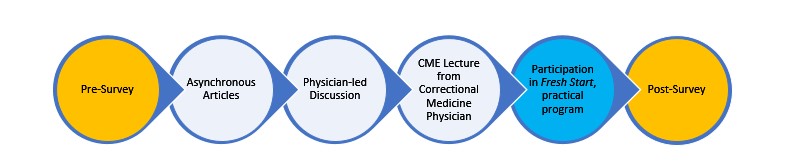

Participation in the curriculum consists of being assigned to read 2-4 journal articles with the most up-to-date material and information regarding the healthcare of the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated population. After completion of these articles, the next phase of the curriculum includes attending a discussion/presentation surrounding incarcerated and formerly incarcerated population healthcare, led by a physician with experience in this niche of medicine. The physician may be accompanied by 2-4 medical students who have completed a correctional medicine elective rotation, available to share their experiences and answer questions. This presentation will also discuss the assigned journal articles and emphasizes its most pertinent points. The final piece, before post-curriculum testing, was attendance of an accredited continuing medical education (CME) correctional medicine talk. Our institution was fortunate to host such an event in person, but future variations could include this piece asynchronously/virtually. Each discussion was approximately 1 hour, while the asynchronous journals were sent out upon enrolling in the curriculum and were self-paced.

Lastly, during the entire duration of this curriculum, enrollees were simultaneous participating in a practical program, which at our institution was titled “Fresh Start”. The program consisted of a 1 hour per week time commitment, where participants and FIPs would meet at a local community center for 1 on 1 counseling regarding topics specific and pertinent to FIP health. Examples included tobacco cessation, diet and lifestyle modifications, interview prep and job application assistance, securing housing, and several others. These hour-long sessions started with a previously prepared power point on the day’s topic and then breakout sessions for the 1 on 1 counseling.

We believe that introducing a physician-led, discussion-based curriculum – supplemented with various articles regarding the formerly incarcerated population and in conjunction with a practical component – will improve the knowledge/skills/attitudes surrounding health outcomes of this vulnerable population. A visual breakdown of this program can be seen below:

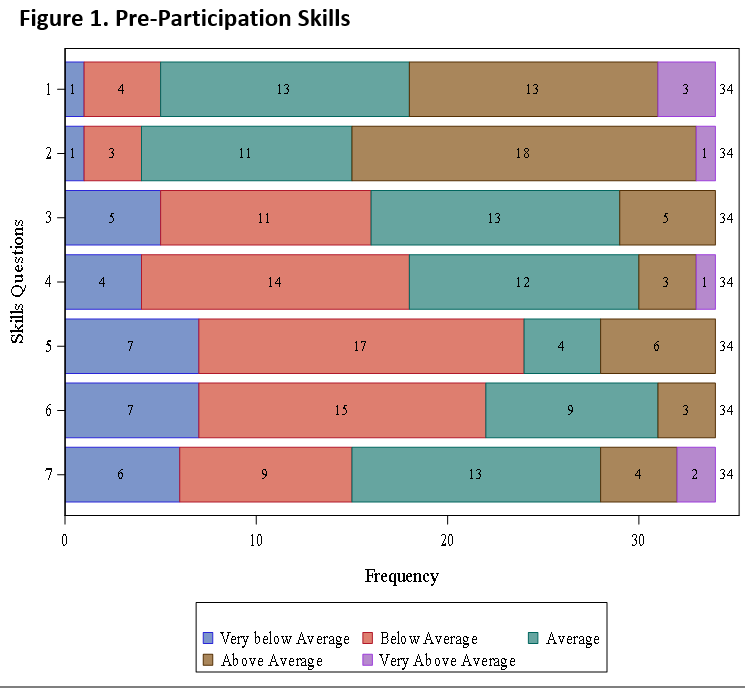

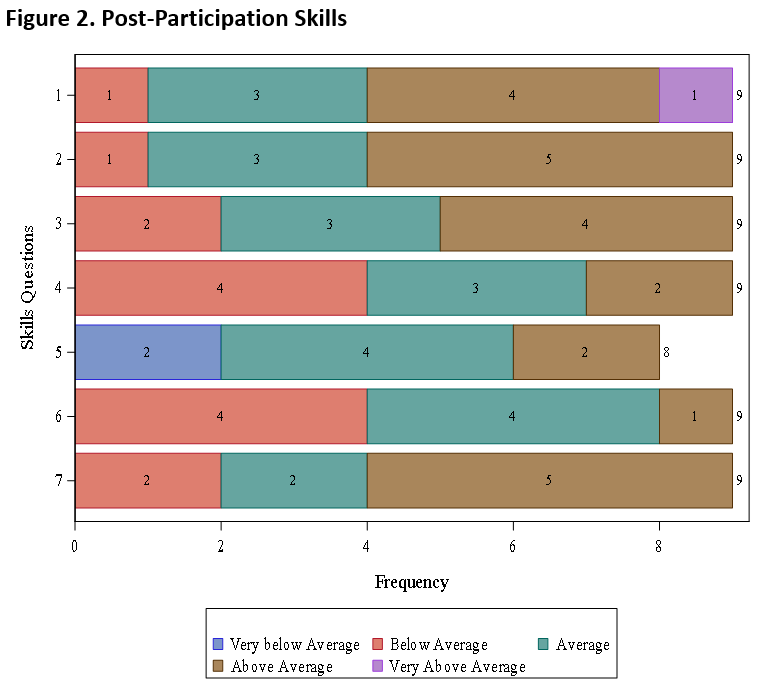

The results yielded from this study showed a uniform increase in knowledge, skills, and attitudes across the board from pre-survey to post-survey responses upon completion of the curriculum. Particularly significant improvement was shown in the knowledge arena, especially as it pertains to barriers for returning citizens to overcome and statistics regarding hospitalization rates of formerly incarcerated populations. Improvement in skills were especially evident in the participants self-evaluated ability to perform nutrition counseling specific to the needs of returning citizens and advising returning citizens on topics related to gaining access to healthcare. Lastly, attitudes were improved in the way of acknowledging greater appreciation for issues faced by returning citizens related to finding housing.

TABLE 1. Changes in Student Knowledge

KNOWLEDGE | PRE % CORRECT | POST % CORRECT |

1. Which of the following statements is true regarding the prevalence of infectious disease between FIP and general population? | 91.18 | 100 |

2. Which of the following statements is true regarding substance abuse disorders and violence during incarceration? | 91.18 | 100 |

3. Which of the following statements is true regarding the difference in incidence in chronic disease and disabilities in the elderly incarcerated population compared to the general population? | 100 | 100 |

4. Which of the following social determinants of health is the biggest challenge for returning citizens to overcome? | 17.65 | 88.89 |

5. According to one study, what is the rate of hospitalization of formerly incarcerated population within 90 days of release? | 55.88 | 88.89 |

6. According to one study, during the first 2 weeks after release, what is the increased rate of mortality of FIPs compared to the general population? | 61.76 | 66.67 |

7. Which of the following is NOT mentioned as an important component of re-entry for the FIP, in an AAFP article? | 67.65 | 100 |

Question by question results for increase in student knowledge based on the pre and post MCQ test. Greater than 30% of participants gained additional knowledge on several questions, and some degree of improvement was seen with every question.

Table 2. Changes in Student Attitudes

ATTITUDES | PRE-AVERAGE | POST-AVERAGE |

1. I can appreciate issues faced by FIPs related to finding housing | 4.4 | 4.8 |

2. I can appreciate issues faced by FIPs related to findings employment | 4.5 | 4.8 |

3. I can appreciate issues faced by FIPs related to finding health care and health insurance | 4.4 | 4.7 |

4. I can appreciate issues faced by FIPs related to reintegrating into their families and communities | 4.5 | 4.8 |

5. As a physician, I will take my time to ensure I am addressing all possible barriers to adequate health car e when working with FIPs | 4.8 | 4.9 |

6. If you were offered a position as a correctional medicine physician today, how likely would you be to take it? | 3.0 | 3.3 |

Question by question results yielding increased averages for post compared to pre curriculum average attitudes towards various topics of FIP health care.

Doctors are both privileged and tasked with the responsibility of providing evidence-based health care of the highest quality to all members of society, who trust them with their lives. Patients rely on the esoteric knowledge that has been entrusted to physicians in hopes that it will allow them to live a happy and healthy life, which every person deserves. If nothing else, doctors must remember the oath they took before first dawning their unstained, cleanly pressed, new [albeit short!] white coats; “First, do no harm”. If we neglect to learn the intricacies of an entire, rapidly growing, and almost certain-to-be-encountered demographic of patient, we are not upholding our end of the bargain. We risk “doing harm”.

Among inmates in federal, state, and local prisons/jails, approximately 40% on average suffer from at least one, and usually multiple, chronic medical conditions. Mental illness, substance abuse, and unhealthy lifestyle habits are among the most common issues encountered by this population, all of which can be studied in detail and then managed, at least in part, via appropriate education and motivational counseling.10Even despite the 8th Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment”, prisoners access to healthcare, and the quality of that healthcare, is often deficient resulting in FIPs that are arguably in worse condition and are more vulnerable upon release compared to pre-incarceration. This calls for improvements in the correctional healthcare system and community health services that can meet the specific needs and mitigate risks for this population – it calls for physician education.

A first step in this direction towards adequate education surrounding FIPs should be simple, easily and widely implementable, and effective. An extracurricular elective, which combines components of both traditional education and Peer-assisted learning (PAL), would check off each of these boxes. PAL has become increasingly popular over recent years, and for good reason. These programs have shown clear evidence of benefit to both the teacher (senior members of student-run program and/or lecturer), the learner (novice members of student run program and/or lecture attendee), and the subject (FIPs participating in the student-run program).11 Particular success has been shown when formal teaching practices are embedded into the educational modality, as done with this particular curriculum.11

In fact, results from the current study revealed that the proposed curriculum was not only well-received, but that it was effective. Students uniformly increased not only their knowledge and skills regarding FIPs, but their attitudes also shifted to be more positive, and many students even indicated a newfound interest in having correctional medicine be a part of their future practice. A number of quotes were also recorded from participating students, highlighting particularly appreciated portions of the curriculum below, broken down by category:

“The pre-lecture journal articles [on FIP health] provided me with so much more insight into caring for this population, and [Dr.X’s] lecture was even more illuminating than that!”

“[This curriculum] helped me to build a base from which I can reflect on experiences I have had and will have when working with formerly incarcerated individuals, to truly understand their specific needs at that point in time.”

“When working with a unique population such as this, simple things like getting an accurate history and uncovering their personalized barriers to a healthy lifestyle are a skill in and of themselves, and I definitely enhanced that skill through this curriculum.”

“In order to be prepared to counsel an individual on healthy lifestyle habits such as diet and exercise, you must first examine and build your own knowledge on these topics. This was a great exercise in enhancing not only FIP-specific health choices, but in augmenting my own knowledge of the aforementioned topics.”

“I now look forward to working with this population in the future.”

”This is a population I hope to see and help in my future practice.”

“The FIP is clearly at risk and deserves attention that is not received in medical school to properly care for their needs.”

Overall, the proposed curriculum is merely a skeleton. The above-mentioned quotes are provided to highlight which components of the elective were principally well-liked and effective, but, as was the intent, this curriculum is highly flexible and can be modified to fit the local needs and goals of whichever institution may adopt it.

Additionally, components may be added to bolster the educational value, with a specific suggestion of ours being the AAMC correctional medicine videos provided on their website (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-research/health-equity/community-engagement/toolkits).

From this study, we can conclude that a simple, easily implemented, and widely reproducible curriculum in correctional medicine can positively impact a medical student’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards the topic. This is especially important for clinicians who are training in the United States; the country with the single highest incarceration rate in the world.2 US-trained medical students will almost undoubtedly be charged with the care of an incarcerated or formerly incarcerated individual at some point along the trajectory of their training and/or career, and this care cannot be best addressed without a fair understanding of the circumstances, unique health disparities, and -environmental barriers that this population faces. What this study has done is served as a pilot investigation establishing a positive response and foundation for further advances in the assimilation of correctional medicine into undergraduate medical education.

The main limitation of this study was the amount of medical students (particularly M1s) who were willing to complete the entire program, not being as large as we had hoped. A smaller sample size of those who completed the post curriculum survey, compared to the pre-curriculum survey, was thus encountered. We would consider offering credit or other incentives to get more students to complete the curriculum in its entirety in the future.

For future directions, we are working on developing a plan for sustainability. This could involve combining efforts with other, related student groups to link participation in this program directly into a clinical, correctional medicine experience.

Including a mandatory shadowing component so students can experience healthcare during incarceration would allow for better understanding of the changes experienced post-incarceration, but would also risk driving up the attrition rate of participating students. Lastly, we would reconsider the timing of the pre-survey, offering it at the start of first year to limit prior FIP exposure. The survey could then also be administered to the entire first year student body as a cohort so that outcomes in those who participate in the curriculum can be compared to a more robust control group. This would also help in increasing the overall sample size.

Kyle Wieschhaus, MD is an Orthopaedic Surgery Resident at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, VA. He is interested in global health efforts, both abroad and domestic.

Amy Blair, MD is with Loyola University Chicago, Stritch School of Medicine.

Lucia Garcia, MPH, Med is with Loyola University Chicago, Parkinson School of Health Sciences and Public Health,

Maria Poonawalla, MD is University of Chicago, Department of Internal Medicine

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.