Sokol D, Ghosal V, Chen. Medical malpractice reform and its impact on lawsuits and damages payments. HPHR. 2021; 30.

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD29

We examine a natural experiment: the impact of Florida’s 2013 medical malpractice reform legislation on malpractice lawsuits and damages payments. We identify changes in the number of liability claims and payments of liability to plaintiffs between the pre-and-post 2013 Florida Malpractice Reform legislation enactment. We also examined results across various sub-groups. These include results: (a) across 31 medical specialties and professions, and dentistry; (b) by categories such as severity of injury, and risk groups; and (c) grouping by whether the paid claims are relatively small or large. We find a relatively large drop in the total number of claims and an increase in the average payment. However, the aggregate picture masks heterogeneity across some of the sub-groups. These findings suggest some changes for the design of medical malpractice tort law.

Law shapes healthcare spending and behavior. Fundamental to healthcare policy decisions are a tradeoff between provision of medicine and incentives to regulate negligent behavior through malpractice.[1] Tort law polices against malpractice by healthcare professionals can lead to justice for wrongful acts via malpractice claims. However, setting malpractice law to an overly lenient threshold may raise costs for healthcare providers (because of the need of increased insurance by medical providers that is passed to customers) and shift incentives for healthcare professionals in ways that such professionals may engage in overly “defensive” medicine to protect themselves against potential liability. Overall, medical malpractice payout amounts are increasing at an annual rate of about 2% in recent years.[2]

While medical malpractice issues have been longstanding, the debate as to its relative benefits and costs remains fierce. The goals of malpractice laws are to compensate victims and to deter bad behavior. Regarding costs, the threat of malpractice litigation caused more than 50% of respondents to a survey by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to change their practice, especially in the case of high-risk procedures.[3]

The risk of medical malpractice lawsuits can vary substantially by specialty, [4] where some medical specialties have a much higher risk, often because some procedures are risker than others. In Jenna et al, the projected risk of facing malpractice claims was 36% in low-risk medical specialties (such as pediatrics and family medicine), compared with 88% in high-risk physician specialties (such as neurosurgery and thoracic–cardiovascular surgery) by the age of 45 years, with this risk increasing to greater than 75% by 65 years of age.[5]

As a result of the costs of healthcare, law has shifted in how it has calibrated the value and excesses of tort liability in medical malpractice. States have introduced several types of tort reform to try to curb what may be excessive tort liability.

Though there have been several medical malpractice reforms across states and over time, [6] significant research gaps remain in terms of understanding the outcomes of medical malpractice reforms and the mechanisms for such outcomes. Sound policy requires an empirical understanding of the tradeoffs involved to create legal rules that deter bad behavior but do not chill necessary risk-taking and innovation. Our study aims to provide a better understanding of outcomes by focusing on Florida’s 2013 changes in medical malpractice legislation and its impact on claims. [7] The focus on one state is helpful in that a single case study potentially allows for greater understanding by a broader audience, which may lack expertise in medical malpractice litigation and tort reform. Therefore, understanding these changes provide an understanding potentially more broadly of how to best address medical malpractice through tort law.[8]

Florida has among the highest number of medical malpractice claims of any state.[9] Because of the size of Florida, its diversity, and the increase in medical tourism to the state, [10] it may be uniquely situated to study evolving trends in the intersection of law and healthcare practice. Our findings show that while Florida’s legal reforms have led to fewer total number of payouts and lower total payout, the average payout per malpractice suit has increased. Our focus on state level claims across specializations allows for a more nuanced study relative to national studies and allows for inferences to be made as to potential causation of legal change to healthcare delivery.

In 2013, the Florida legislature approved reforms to medical malpractice law (SB1972) to contain the high medical malpractice costs in Florida, potentially reduce the number of weak or bogus suits, and establish a more pro-doctor litigation practicing environment.[11] To date, the impact of Florida’s 2013 malpractice reform legislation (implemented on May 1, 2013) on the number of malpractice lawsuit settlements, the liability payments to plaintiffs, and its potential differential effects across medical specialties have not been studied as thoroughly as prior reforms.[12] Unlike prior studies for Florida, we disaggregate the data to the specialty level, which we compare to both national studies and state level studies in other states.[13]

The 2013 legislation contained several features that impacted malpractice claims and outcomes. First, an expert witness who testifies against a physician should be in the same specialty as the physician, rather than a “similar” specialty that was allowed pre-reform. This provision limits the number of physicians who are qualified to be a witness in court to true specialists. Increased specialization of experts may limit frivolous cases because specialists in a tightly-matched area of practice are more likely to understand the specific risks of medical practice better than non-specialists. It may also be the case that this closely matched level of specialization of testifying physician-experts also provided a setting where errors by doctors were highly penalized. Overall, this aspect of change in rules post-reform will likely have led to lower number of suits, but the effects on liability payments is somewhat ambiguous ex ante.

Second, the legislation allowed physicians to consult the attorney referred by their medical malpractice insurance provider. The prior law prevented certain ex-parte discussions between the attorney referred by the insurer and physicians involved in the malpractice case, although this part of the reform was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court on health privacy grounds.[14] This consultation may reduce information asymmetries by giving insurers a more holistic account of other health conditions unrelated to the malpractice and therefore potentially changing the amount offered for settlement. Ex ante, it is ambiguous which way this change would impact settlements overall as it might increase some settlements because of a higher risk of liability but decrease others.

Third, post-reform the defendant physician’s lawyer is permitted to meet the plaintiff’s treating physician to discuss the plaintiff’s medical record. This may reduce information asymmetries and limit discovery costs. Following this, what predictions can we make if any on outcomes related to number of suits and liabilities in the post-reform equilibrium.

The 2013 legislation offers a natural experiment to examine the impact of medical malpractice reform. A unique aspect of our study is that it uses a rich dataset from the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation (FOIR) to examine the impact of medical malpractice reform that includes all financial settlements for health care professionals. Earlier work on Florida medical malpractice did not disaggregate results across medical specialties[15] or focused on particular specialties.[16] Other studies use results from legal databases that are subject to limitations because these databases only collect decided cases.[17] In contrast, our study examines data on all settled claims. Due to this rich data, our study is able to identify shifts across specialties in Florida to medical malpractice reform, as well as examine the effects by risk-group and claim size.

Our study uses claims data recorded by FOIR from 2010 through 2018 to identify how legal reform affected malpractice suits and damages awarded. Established in 2003, FOIR is a government agency that is responsible for all activities concerning insurers and other risk-bearing entities in Florida. FOIR requires all insurers to report any settlement or judgment of “any amount” paid by the insurer – the actual settlement amounts.

The Florida malpractice reform year is 2013. We use two sample periods to delineate the pre- and post-reform periods for Florida’s legal reform. We use claims data over 2010-2012 as the “pre-reform” period. In contrast to prior studies, we do not include data reported before this period because Florida’s state university affiliated hospitals did not report malpractice claims at the individual doctor level before this time. We do not include 2013 as it would contaminate the data with potential reform-year information.

For the “post-reform” period, we use data over the period 2016-2018. We use 2016 as the start of the post-reform period to reflect the timing for litigation started in 2013 to reach a settlement. The exact timeline of injury to case filing to financial settlement can vary significantly by case.

Prior literature suggests that in many cases it can take up to 20-24 months for settlement after the case has been filed.[18] Additionally, on average, physicians can spend nearly 11 percent of their 40-year careers with an open, unresolved malpractice claim.[19] As we do not want our post-reform data period to be contaminated by the reform year injuries and follow-up litigation process, we use 2016 as the year that is arguably clear of this problem. Our final year is 2018, as this is the last year for which we compiled detailed data.

The key outcomes of interest in our study are: (a) changes in the total number of liability claims reported to FOIR between the pre- and post-reform periods, 2010-2012 and 2016-2018; and (b) changes in the average payment of liability to the plaintiff in the pre- and post-reform periods. We examine the total number of claims and average payment per claim in our sample, as well as several groupings of interest, such as those related to (i) severity of injury, (ii) risk factors, and (ii) monetary size of the claim.

First, we segment our sample into groups ‘by severity’. Our assumption is that less severe claims would be reduced post-reform so that the focus more likely would be on more severe claims. The basis for this assumption is that medical malpractice reform operates as a screen. The more difficult the threshold to overcome the malpractice reforms, the greater the chance is that the injury was more severe (higher stakes severity will lead to more sophisticated lawyers because the stakes are higher) and that the more severe claims are more likely than the pre-reform period to be more likely for a court to find in favor of the plaintiff. In the medical professional liability claim reporting form, the severity of the patients’ injury is recorded using a standard 9-point severity scale. These include emotional injury only, temporary slight injury, temporary minor injury, temporary major injury, permanent minor injury, permanent significant injury, permanent major injury, grave injury, and death.[20] The average payment to the plaintiff we examine is also stratified by the severity of injury.

Second, we examine the issue where provision of medical care is in different “risk” categories. There are distinct issues for “claim-prone” physicians – those who tend to practice more defensive medicine, who may potentially increase patients’ medical expenditures.[21] Almost 1% of physicians accounted for one-third of total paid claims.[22] The risk of having at least one malpractice claim by the age of 45 among physicians in high risk group was double that of their counterparts in low-risk categories.[23] Tort reform is broad but these different risk categories may be impacted differently by a general application of law.

Previous studies find physician-protective legislation reform has moderate effects on the practice of defensive medicine.[24] However, there are fewer studies on the impact of legislative reform on the number of suits and liabilities by different “risk groups.” The 2013 reforms might conceptually produce different results across risk groups because the reforms may potentially have a greater effect on the higher risk practices which also tend to generate larger settlement payouts.

To examine this, we categorized our data into 3 subgroups: high-risk, medium-risk, and low-risk, based on previous method.[25] Briefly, the high-risk group includes emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecologic surgery, and radiology; the low risk group includes general and family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics; other specialties were classified as medium risk. We create these sub-groups as the literature also suggests that the larger the potential claim, the better the chance of a more skilled lawyer getting involved in a case.[26]

Third, we examine liability claims across different monetary “claim size”. We create these sub-groups as the literature suggests that the larger the potential claim, the more likely it is that a better lawyer is involved. As the payout is higher, the quality of lawyers is likely to improve with size of cases and their complexity.[27] To examine the effects of claim size, we created two sub-groups by the dollar amount of settlements, to disaggregate small claims from large claims. In Group 1 all settlements are less than or equal to $100,000, what many plaintiff’s lawyers or insurance company defendants might think of as a small claim. In Group 2, all settlements are greater than $100,000, what plaintiff’s; lawyers or insurance company defendants might think of as larger claims.

To summarize our empirical strategy, we examined the number of liability claims and average payment per claim for our full sample, and groupings by severity of injury, risk factor, and claim size.

Next, we turn to discussing our results. We studied a total of 3,783 liability claims. In our discussion below of the data, we use 2010-2012 as the pre-reform period, and 2016-2018 as post-reform. Overall, the total number of liability claims in Florida declined from 2,373 during 2010-2012 to 1,410 during 2016-2018. The decline in the number of claims parallels some prior studies that show decreases after malpractice reform using national data from the NPDB,[28] or state level data from Illinois and Texas.[29] Settlement payment amounts in Florida dropped by 17.6% (from $351,650K to $289,710K) after the enactment of malpractice reform.

Next, we examined data by severity of injury. We found all categories of injury severity had declines after reform, with the category of ‘temporary slight’ decreasing the most (about 68%), followed by ‘grave’ (53%) and ‘permanent minor’ (46%). The average amount of payments increased post-reform for all levels of severity (except severity category as “emotional only”). For example, the average payment increased the most in the category of ‘temporary-major’ ($82,452, or by 96%) compared to pre-reform, followed by ‘temporary slight’ ($18,457, 92%) and ‘permanent major’ ($159,051, 65.8%). This suggests that reforms removed outlier cases.

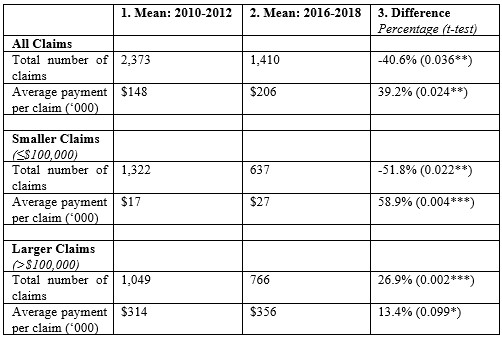

Finally, we examine results by claim size. Our two groups are: Group 1 (small claims) with settlements less than or equal to $100,000; and Group 2 (larger claims), with settlements greater than $100,000. For Group 1, the total number of liability claims decreased by 51.7% from 1,322 during 2010-2012 to 637 during 2016-2018. Similar trend was observed in the total payments, which decreased by 23.2%. However, the average amount of payment increased by 58.9% from $17,079 during 2010-2012 to $27,223 during 2016-2018. In contrast, Group 2 had a relatively smaller change. Between 2010-2012 and 2016-2018: the total claims decreased by 26.9% from 1,049 to 766; the total payments decreased by 17.2% from $329,076 to $272,371; and the average payment increased by 13.4% from $313,704. When examining the changes between smaller and larger payout cases, the decrease in the smaller cases is more pronounced. This suggests that smaller cases, more likely to be nuisance cases, were more effectively screened out due to the 2013 reform for reasons discussed above.[30]

In the table below, we summarize some of the differences between the pre-and post- reform samples.

We examined the number of liability claims and payments to plaintiffs before and after the enactment of the 2013 Florida medical malpractice reform legislation. Comparing the overall patterns from the pre-reform period (2010–2012) to the post-reform period (2016–2018), we found that while the total number of liability claims and total malpractice payments were lower in the post-reform period, the average payment to plaintiffs were higher. Focusing on the by severity of the injury category, the average payment increased for 8 of the 9 categories. This may indicate that the changes in the law likely may have screened out weaker cases and left stronger cases of medical malpractice.[31] This has important implications for the provision of medical services. Doctors and hospitals may be changing their practices and behaviors as to defensive medicine and business models based on increased legal certainty to screen out weaker cases. Relatedly, they may be creating improved treatment and related protocols to minimize suits. This development is not easily quantified but as weaker cases on the merits become screened out, greater legal certainty may well bring larger payments on errors. Thus, hospitals and physicians have greater incentives to create more effective treatment protocols.

The composition of the severity of injury involved in malpractice claims also changed slightly before and after the legislation. The proportion of claims from permanent injuries, grave injuries, and death reduced from 70.5% in pre- to 66.2% in the post-legislation period. About 32.6% claims in pre- and 30.4% claims in post-legislation periods involved death. As expected, the average amount of payment to the plaintiff was associated with the severity of the injury, where the payment for temporary minor injury was the lowest, and the payment for the grave injury was highest. Brown et al.[32] reported a similar pattern but with national data based on survey data rather than with data from actual insurance settlements.

Understanding risk factors more clearly across specializations may lead to better planning, which can create increased efficiencies for the provision of healthcare. With a focus on using tort law reform to focus on the more egregious claims of malpractice, the entire healthcare system benefits. Doctors have improved incentives to offer better treatment, patients get more optimal treatment, and clearer cases of malpractice get properly penalized through litigation.

Our study has some limitations. First, because the FOIR database does not contain information on physicians who had no liability claims, we were not able to estimate the proportion of physicians who had malpractice claim by medical specialty. Second, the FOIR database does not capture the claims against physicians who moved out of Florida after medical malpractice reform. Third, the FOIR dataset only reported the major medical specialties and fields in liability claims, and we could not examine how the legislation influences malpractice lawsuits for subspecialties. Even when providing the same medical procedures, some subspecialties may be more vulnerable to malpractice lawsuit than others. Further, lawyer attributes based on location and skill (with higher skilled lawyers likely getting better payouts) may impact settlement amounts.

This study provides estimates of malpractice liability claims and payments to the plaintiff by medical specialties before and after the enactment of Florida malpractice reform legislation. There was a marked downward trend in the number of claims and total payments, with heterogeneity across various sub-groups we considered. Understanding of the factors associated with the variation by medical specialties, especially the causes of increased malpractice claims and average payment, is still limited and warrants continued intensive research. Understanding the dynamics of how tort reform impacts the medical system remains a critical issue for health policy. Without empirical work on the impacts of tort reform across states, legislatures may create incentives that may reduce the quality of healthcare.

Healthcare reform remains paramount in the United States. Costs are too high and provision of care is not as effective as perhaps it can be.[33] With tort reform generally at the state level and with few studies that track changes at the state level across each of the 50 states, it is important to have more studies to better legislate tort liability to make the healthcare system function better.[34] The more studies, the easier it becomes to legislate to reach an equilibrium to counter bad medicine but not chill incentives that improve healthcare and reduce costs.

[1] Benjamin J. McMichael et al., ‘‘Sorry” Is Never Enough: How State Apology Laws Fail to Reduce Medical Malpractice Liability Risk, 71 Stan. L. Rev. 341, 359-60 (2019); Kenneth S. Abraham & Paul C. Weiler, Enterprise Medical Liability and the Evolution of the American Health Care System, 108 Harv. L. Rev. 381, 382 (1994).

[2] Michelle M. Mello et al., The Medical Liability Climate and Prospects for Reform, 312 JAMA 2146 (2014).

[3] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Ob-Gyn Professional Liability Survey, www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Professional-Liability/2015-Survey-Results?IsMobileSet=false.

[4] Adam C. Schaffer et al., Rates and Characteristics of Paid Malpractice Claims Among US Physicians by Specialty, 1992-2014, 177 JAMA Intern. Med. 710 (2017).

[5] Anupam B. Jena et al., Malpractice Risk According to Physician Specialty, 365 New Eng. J. Med. 629 (2011).

[6] Myungho Paik et al., Damage Caps and the Labor Supply of Physicians: Evidence from the Third Reform Wave, 18 AM. L. & ECON. REV. 463 (2016) (providing a review).

[7] This was passed as SB1792 and codified in Fla. Stat. Ch. 766. It went into effect on July 1, 2013.

[8] Wendy Netter Epstein, The Health Insurer Nudge, 91 S. CAL. L. REV. 593, 597 (2018); Allen Kachalia & Michelle M. Mello, New Directions in Medical Liability Reform, 364 NEW ENG. J. MED. 1564, 1565 (2011) (“An oppressive liability environment … can have the unintended effect of ‘over-deterrence’–causing unwanted provider practices aimed primarily at avoiding liability.”); Richard S. Saver, Health Care Reform’s Wild Card: The Uncertain Effectiveness of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 159 U. PA. L. REV. 2147, 2174 (2011) (“Financial incentives powerfully guide physician behavior … above and beyond technical appeals to clinical judgment.”).

[9] Belk, D. Malpractice Statistics, True Cost of Health Care, available at truecostofhealthcare.org/malpractice_statistics/.

[10] Florida Chamber of Commerce. A Strategic Look at Florida’s Medical Tourism Opportunities: Report to Medical Tourism Taskforce, available at http://www.flchamber.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Research_A-Strategic-Look-at-Floridas-Medical-Tourism-Opportunities.pdf.

[11] Florida Senate: SB 1792: Medical Negligence Actions.

[12] Joni Hersch et al., An Empirical Assessment of Early Offer Reform for Medical Malpractice, 36 J. LEGAL STUD. S231 (2007); Neil Vidmar et al., Million Dollar Medical Malpractice Cases in Florida: Post-verdict and Pre-suit Settlements, 59 VAND. L. REV. 1343 (2006). Neil Vidmar et al., Uncovering the “Invisible” Profile of Medical Malpractice Litigation: Insights from Florida, 54 DEPAUL L. REV. 315 (2005); Gary M. Fournier & Melayne Morgan McInnes, Medical Board Regulation of Physician Licensure: Is Excessive Malpractice Sanctioned?, 12 J. OF REG. ECON. 113 (1997); Frank A. Sloan et al., Medical Malpractice Experience of Physicians: Predictable or Haphazard?, 262 JAMA 3291 (1989).

[13] Charles Silver et al., Fictions and Facts: Medical Malpractice Litigation, Physician Supply, and Health Care Spending in Texas Before and After H.B. 4, 51 TEX. TECH L. REV. 627 (2019); Bernard Black et al., Stability, Not Crisis: Medical Malpractice Claim Outcomes in Texas, 1988-2002, 2 J. EMPIRICAL LEGAL STUD. 207 (2005).

[14] Weaver v. Myers , 229 So. 3d 1118 (Fla. 2017).

[15] Neil Vidmar et al., Million Dollar Medical Malpractice Cases in Florida: Post-verdict and Pre-suit Settlements, 59 Vand. L. Rev. 1343 (2006); Frank A. Sloan et al., Medical Malpractice Experience of Physicians: Predictable or Haphazard?, 262 JAMA 3291 (1989).

[16] Christine Piette Durrance, Noneconomic Damage Caps and Medical Malpractice Claim Frequency: A Policy Endogeneity Approach, 26 J.L. Econ & Org. 569 (2009).

[17] Adam C. Schaffer et al, Surgical Residents and Medical Malpractice, 153 JAMA Surg. 395 (2018).

[18] Randall R. Bovbjerg & Kenneth P. Petronis, The Relationship Between Physicians’ Malpractice Claims History and Later Claims: Does the Past Predict the Future?, 272 JAMA 1421 (1994).

[19] Belk, supra note 7

[20] National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Guideline for Implementation of Medical Professional Liability Closed Claim Reporting, available at naic.org/store/free/GDL-1077.pdf.

[21] David M. Studdert et al., Defensive Medicine Among High-Risk Specialist Physicians in a Volatile Malpractice Environment, 293 JAMA 2609, 2609 (2005).

[22] David M. Studdert et al., Prevalence, supra note 26 at 359 tbl.2 (2016) (“Several physician characteristics, most notably the number of previous claims and the physician’s specialty, were significantly associated with recurrence of claims.”). Studdert et al., Defensive medicine, supra note 20.

[23] Anupam B. Jena et al., supra note 5.

[24] Emily R. Carrier et al., Physicians’ Fears of Malpractice Lawsuits Are Not Assuaged by Tort Reforms, 29 Health Aff. 1585 (2010).

[25] Aaron E. Carroll & Jennifer L. Buddenbaum, High and Low-Risk Specialties Experience with the U.S. Medical Malpractice System, BIOMED CENT. HEALTH SERVS. RES. (Nov. 6, 2013), http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-13-465.

[26] Albert Yoon, The Importance of Litigant Wealth, 59 DePaul L. Rev. 649 (2010); Marc Galanter, Why the “Haves” Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change, 9 Law & Soc’y Rev. 95 (1974).

[27] Id.

[28] Michelle M. Mello et al., Medical Liability Climate, supra note 2; David M. Studdert et al., Prevalence, supra note 20.

[29] Mohammad Rahmati et al., Insurance Crisis or Liability Crisis? Medical Malpractice Claiming in Illinois, 1980–2010, 13 J. Empirical Legal. Stud. 183 (2016); Bernard Black et al., Stability, supra note 16; Bernard Black et al., Defense Costs and Insurer Reserves in Medical Malpractice and Other Personal Injury Cases: Evidence from Texas, 1988-2004, 10 Am. L. & Econ. Rev. 185 (2008).

[30] Mohammad Rahmati et al., Screening Plaintiffs and Selecting Defendants in Medical Malpractice Litigation: Evidence from Illinois and Indiana, 15 J. Empirical L. Stud. 41 (2018).

[31] Id.

[32] Terrence W. Brown et al., An Epidemiologic Study of Closed Emergency Department Malpractice Claims in a National Database of Physician Malpractice Insurers, 17 Acad. Emergency Med. 553 (2010).

[33] Niek Stadhouders et al., Effective healthcare cost-containment policies: A systematic review, 123 Health Pol. 71 (2019); David A. Hyman & Charles Silver, Medical Malpractice Litigation and Tort Reform: It’s the Incentives, Stupid, 59 Vand. L. Rev. 1085, 1086-87 (2006).

[34] Mitchell Polinsky & Steven Shavell, Costly Litigation and Optimal Damages, 37 Int’l Rev. L. & Econ. 86 (2014).

D. Daniel Sokol, JD, MSt, LLM is a Professor of Law at the USC Gould School of Law and Affiliate Professor of Business at the USC Marshall School of Business.

Vivek Ghosal, PhD is the Virginia and Lloyd W. Rittenhouse Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences, and Department Head of Economics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. His research areas include regulatory reform, law and economics, and business strategy.

Guanming Chen is a PhD candidate in the Department of Health Outcomes and Biomedical Informatics, University of Florida. Her research focuses on the health outcome disparities by race/ethnicities, comparative effectiveness of treatment modalities on metabolic diseases, and opioid safe prescribing.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2024 BCPHR: An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal