Avila E, Irfan A, Swinson, W. Displacement and gentrification across the U.S.: The pillage of cultural identity and community. HPHR. 2021; 30.

DOI:10.54111/0001/DD35

An ironic shift in residency is occurring in metropolitan areas across the country such as the Bay Area, Greater Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and Washington D.C. [25, 47, 49, 50, 51, 62] Formerly slighted communities are receiving a makeover equipped with high-end apartments and condos housing a new and evolving workforce. These communities still have remnants of the old brick buildings, community parks, cultural landmarks, and murals of the former community which lived on these plots of land, but the feel of the neighborhood, the culture, feels foreign and pseudo-utopian, to put it mildly.

Many white, affluent residents with college educations are moving to more urban environments in the US. This trend is frequently viewed as gentrification and has been viewed both negatively and positively over the years as economic growth usually increases. It can also be characterized or defined as the forced or involuntary displacement of lower-income, typically non-white, residents in a specific community due to rising costs of housing, amenities, and services. [47, 50] Nearly a third of low-income households lived in neighborhoods are at risk of, or already experiencing external displacement pressures. [76] Some argue that the reduction of blight within a community, improved parks, bike lanes, renovated housing options, and job opportunities, are all reasons to support gentrification. However, to achieve these improvements for a community, we commonly see a reduction of affordable housing, lack of support and training to obtain these new, well-paying jobs that come to metropolitans (e.g. NYC, DC, and the Bay Area) and “booming” cities (e.g. Austin, Charlotte, and Dallas) and an influx of usually white, more affluent, highly educated residents, which displace former residents. [25] These neighborhoods become exclusionary and disallow low-income residents from moving in.

The irony is that white families moved to newly constructed suburbs in the past to escape from integration, a phenomenon called white flight. [30] Communities were developed throughout the country with ranking systems and agreements in place with banks promising to ban blacks from moving into their communities; all while the local, state, and national governing bodies supported these efforts. [30] In 1934, Congress and President Roosevelt created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) which insured loans from mortgage lending banks. The FHA labeled racially mixed neighborhoods and white neighborhoods in close proximity to black neighborhoods “too risky” and would not insure loans to buyers very easily. [30] As a result, banks would increase rates and be incentivized to deny integrated urban and suburban community members loans. The FHA also discouraged lending to urban communities in general because they perceived older homes as a transitory gateway of acceleration for lower class occupancy within a community. By 1973, the US Commission on Civil Rights stated that private housing industry and Federal, State, and local governments have been an active participant in housing segregation in the US. [31]

Communities such as East Palo Alto are being surrounded by booming tech companies, yet are seeing their median household income levels stay below $60,000. [37,61] This same community is potentially at risk of displacement due to the SB 50 proposed policy which looks at creating zoning restrictions in the Bay area to up-zone, or develop more homes, in communities such as East Palo Alto, particularly around transit stops. [38] In Harlem, New York, the average sale price of an apartment increased by 93% from the end of 2006 to 2007, totaling $895,000. [70]

In 2017, Robert McCartney illustrates the gentrification of the District of Columbia. [3] He interviews professor Derek S. Hyra of American University, author of Race, Class, and Politics in the Cappuccino City. [7] The book describes how white millennials swarm to traditionally black urban neighborhoods and take pride in moving into an “edgy, authentic” community, bragging about violence through laughter and jokes as a conversational piece. These same communities in major cities and metropolitan areas such as the DMV area, Detroit, San Francisco, and Brooklyn, are even seeing their names change as new residents and businesses emerge and alter the environment.

Real estate advertisement companies have been accused of changing names of communities to advertise their new businesses and homes in a new light as opposed to their old communal roots. [34] Back in 2017, Harlem was a target of rebranding as Keller Williams real estate company attempted to divide Harlem’s West 110th st to 125th st into SoHa, short for South Harlem. [34,35] A similar issue occurred in Philadelphia as South Philly became divided into smaller cliques such as “Graduate Hospital” and “South Rittenhouse.” [34]

Trump’s 2019 executive order to establish a council on eliminating Barriers to Affordable Housing Development will only further promote the gentrification of cities throughout the US by reducing or eliminating building regulations and restrictive zoning policies. But many advocates, such as the “Yes In My Backyard” organization and the National Low Income Housing Coalition, are concerned that this will further segregate communities by allowing development companies to build affordable housing in already low-income communities, not in the wealthier or sought-after areas. [46]

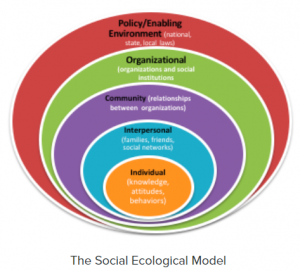

This phenomenon also affects those who are fortunate enough to survive the onslaught of gentrification. Longtime residents in the Bay area were found to face overcrowding and substandard housing, loss of community services and institutions, and financial distress. [51] Those who are displaced are forced to combat disruptions in adequate and consistent health care, loss of community support networks, additional financial distress, longer commutes, and experience direct negative effects on their mental health. [44, 51] Applying the socioecological model (Figure. 1) to this phenomenon, we can see how changes in the community can affect the individual and disrupt their interpersonal and communal ecosystem. Additional environmental health outcomes include decreased life expectancy, decreased quality of life by sacrificing basic needs for rent such as healthy food and health care.

Longer commutes also impact student’s well-being as their sleep and exercise regimen become disrupted. In addition to affecting students, generally, longer commutes have been associated with increased stress and reduced time for health-promotion activities such as adequate sleep and exercise and decreased mental functioning and health. [51] Furthermore, this displacement can cause negative effects on employment due to lack of reliable transportation, disruption of social networks, routines, and an increased risk of entering a homeless shelter due to a tight housing market with low support systems. [51] By disrupting social networks, research has also shown that tight-knit communities have lower rates of violence, lower mortality, and self-reported health is higher. [51]

Lastly, communities have formed goals or plans to reduce their carbon emissions as climate change becomes a bigger buzz word every month. Residents in cities such as New York City, Minneapolis, and Los Angeles are being pushed out before they can reap the health benefits of clean air from the re-greening of their neighborhoods. Furthermore, they are consistently cut out of the development process of these long-term development plans as consultants primarily develop these city goals. [71] These environmental injustices and sustainable contradictions are similarly seen in Portland [72] and other major cities across the country which were unequally burdened by toxic waste facilities and other environmental pollution sources. [73, 74] Many of these areas are listed Brownfields, Superfund sites, or are identified as potentially environmentally hazardous sites. [72, 75] These neighborhoods were often inhabited by minorities [75] who were already relegated to these areas previously through federal initiatives and policies supporting segregation throughout the country. [20] Now, as communities are changing as a result of clean air initiatives and policies to combat climate change, white, wealthier residents are relocating back to urban environments where their environment is becoming cleaner and more natural.

Policies have the potential to affect housing both positively and negatively. In Richard Rothstein’s book, The Color of Law, he details how the government supported redlining and housing segregation.[20] Examples such as housing discrimination practices in major cities barring blacks from moving into white neighborhoods and, more specifically, onto streets with predominately white residents show us the level of influence the government had on impacting public and private housing. A more recent example is Proposition 13. [64] Current residents have a cap on their property taxes which, in theory, should have helped lower-income communities and residents from being booted from their homes. However, California renters do not benefit from this tax break, and commercial properties do. [64] So, companies such as Disneyland and Facebook, benefit from these low taxes while renters take on the increased costs. Couple this with California’s high taxes on gas, food, and other aspects of living, a family’s financial burden increases along with their risk of being displaced.

Policies in Los Angeles (LA) appear to try and address the housing demand in ways which are being perceived as unique in some cases, but very typical of gentrifying norms as well. LA is pursuing Skid Row as a new site of urban development and zoning due to its proximity to downtown and other amenities. Many residents are low-income renters, single room occupancy-hotel (SRO) renters, in homeless shelters, or they reside on the streets in tents.[47] This community, although blighted by many factors, is still home to many people who cannot afford to live elsewhere in LA’s expensive market which is steadily rising. The Inner City Law Center places affordable housing, or a lack thereof, as the first priority for Skid Row residents as housing stability is required to effectively utilize social and medical services. [47] The center further supports the Central City community plan developed by three grassroots organizations highlighting guiding principles for city and state decision-makers to make informed and inclusive choices regarding the development of Los Angeles.

In 2013, the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability published a gentrification and displacement study focusing on inclusive development strategies regarding involuntary displacement and relocation within the metropolitan area of Portland due to changes in the housing market such as the fluctuation of affordable housing.[50] Following this investigation, the researchers recommended similar strategies to prevent further gentrification such as introducing new regulations, policies, and engaging with private developers and community actors to reduce this growing trend.[50] By investing in pre-established communities, home-values will increase in pre-established, low-income communities, which can create unintended consequences for low-SES families. Understanding that public officials are playing a factor in the housing market by developing these neighborhoods is important in mitigating gentrification and housing rate fluctuations.

Pittsburgh’s Hill District was the focus of a strategy assessment in 2011 to address gentrification concerns as it sits in a desirable location. This city has a wealth of Black/African-American culture as it was a historically prosperous and influential black neighborhood before the Civil Rights movement. A victim of redlining and other government-supported segregation practices, the Hill District saw its housing market deteriorate over time and is now a site for new private development. This manuscript proposes to keep families protected from practices such as temporary relocation as most families refuse to go through another relocation, or low-income residents such as the elderly or disabled, are at risk of losing temporary housing before permanent housing is built. Couple this with numerous studies documenting associations between the onset of depression, exacerbation of mental illness, domestic violence, marital breakdown, increased substance abuse, decreased academic performance, and homelessness,49 these displaced communities and families are at risk of worsening their socioeconomic status instead of improving it through additional communal resources. Programs and strategies such as inclusionary zoning, affordable rehabilitation for resale, subsidy protection are highlighted in this strategy proposal.

In the Bay Area, Oakland and San Francisco have undergone a decades-long gentrification process that hit multiple different neighborhoods at different times since the 1990’s. [51] From 1990 to 2011, white homeownership more than doubled in the Mission district of San Francisco, and white renters in historically black neighborhoods such as North Oakland, and throughout the rest of Oakland, increased while the black population decreased drastically. [51] Within late-stage gentrified neighborhoods, black and white mortality rates have the greatest disparity, illustrating the disastrous health effects of gentrification. [51]

Communities of color and lower socioeconomic status, such as those in the Bay area, have been historically likened to “sacrificial lambs” in the name of urban renewal or urban development. Communities such as Barrio Logan where Chicano park resides, have been altered through policy to better serve growing suburban areas and, in some cases such as in Harlem, NY, real-estate developers and agents have attempted to rename and rebrand Harlem as ‘SoHa,’ further stripping a historically black neighborhood of its rich culture and identity. [52]

In Minnesota, 51% of residents who are experiencing homelessness are considered youth and many others cite increase in monthly rent as their reason for moving to a shelter. [29] Shelters are options for temporary housing, but often the shelters are underfunded, undersupported, and are not safe for guests. Minneapolis, however, has enacted a comprehensive up-zoning plan called “Minneapolis 2040” to address unaffordable housing in the metropolitan area by eliminating single-family zoning within city limits to undo racial segregation and to increase multifamily housing. [45] In other communities, residents have often fought to keep out lower-income residents citing lack of affordability for other services and groceries, among other reasons, as to why they want to avoid building affordable housing. [48]

SB 827 State of California – A 2018 bill allowing up to five stories high near every high-frequency mass transit stop in the state. Contesters, including the Sierra Club and “Public Housing in My Backyard” (PHIMBYs), claimed the law would enrich developers and exacerbate gentrification in low-SES communities of color. [53] Washington, D.C.: the Inclusionary Housing program requires residential projects of 10 units or more to reserve 8-10% of the project’s square footage be dedicated to below-market-rate housing or affordable housing. Applicants are required to recertify their wages annually and attend an orientation class prior to move-in. So far, it has not been received well by developers, and the results are mixed. [54]

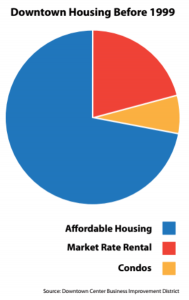

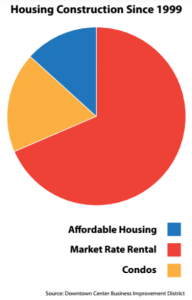

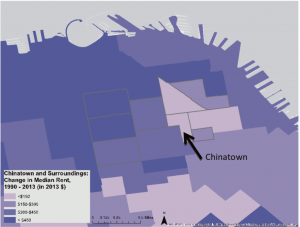

Chinatown, San Francisco: Chinatown has largely resisted displacement of its residents by implementing policies which protect its community from rising costs throughout the rest of the city. In 1986, the Chinatown Rezoning Plan was redesignated as a mixed-use area, separating it from the rest of downtown in several ways while also denying developers from purchasing and redeveloping land for office uses and new residential units. Policies such as the downzoning of the Chinatown core area set height limits on buildings within the area, banned demolition unless it was deemed to protect public safety or for a specific use designated as a necessity for the community, and banned the conversion of residential buildings into other uses. [61] Chinatown also has a large majority of its housing stock as single resident housing (SRO) hotels which an even larger majority are protected by the SF Rent Control Ordinance. [61] Conversely, the number of subsidized and public residential units has not increased since 1990.Many of these units are pre-World War II, making them old and typically in need of repair or renovation. Additionally, the Chinatown Community Development Center and other community-based organizations have teamed up to continually advocate on behalf of the community’s residents to establish tenant associations and pushed for new eviction protections for seniors and residents with disabilities. [61]

Historically, East Palo Alto (EPA), California was established to protect itself and stay a community of color as it froze rents immediately to build tenant protection rules known as the 1988 Ordinance to Stabilize Rents and Establish Good Cause Eviction (updated in 2010). [61] Over the years, the city has reduced parking restrictions on secondary dwelling units (e.g. converted garages), established rent control/review/mediation policies and boards, passed a tenant protection ordinance which includes relocation support, a Condominium Conversion Ordinance allowing the city to block conversions if not presented with significant evidence of attempts to create reasonable alternative housing opportunities, and much more. Despite these numerous programs and protections, nearly 34% of homes are over-crowded in EPA, has low-quality schools, and is viewed as an unsafe, crime-ridden city.

Fiscal year 2020 budget requests a 16.4 percent decrease in the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funding, from the fiscal year 2019 funding levels. The budget proposes eliminating the Public Housing Capital Fund. The Capital Fund provides funding for the “Public Housing Agencies (PHAs) for the development, financing, and modernization of public housing developments and for management improvements. The budget also proposes more than a third reduction in the Public Housing Operating Fund which provides funding to operate the public housing across the nation. Further, the budget proposes eliminating the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program, Choice Neighborhoods Initiative, HOME Investment Partnerships Program, and the Self-Help Homeownership Opportunity Program (SHOP), citing these as ‘ineffective’ programs, and arguing that state and local governments are better equipped to meet the local community needs.

These steep cuts will have a direct impact on one of the most critical social determinants of health: housing. These reductions in funding will hinder the progress towards health equity at the national level, harm low and middle-income families with children, senior citizens, and people with disabilities, further exacerbating national crises of homelessness, evictions, and gentrification. While homelessness and evictions may be self-evident as a direct outcome of rent hikes and reduced funding, gentrification may not be as perspicuous. These deep cuts in public housing will essentially coerce cities into embracing real-estate developers and private enterprises – even more than they already do – to meet the housing needs and budget deficits. In the process, cities lose even more of their limited resources by doling out enormous tax breaks and other financial incentives to attract these developers, in the name of the public-private partnership; the resources that could be spent on much needed social services.

Oregon made a historical move recently by establishing the country’s first statewide rent control act which limits the rates in which rent can increase each year by no more than 7% above annual change in the consumer price index. [65] It is not without faults or limitations as this law only applies to residences which are at least 15 years old, and if a tenant has lived within that unit for at least one year. [65]

To address gentrification within communities, policymakers need to work closely with non-profit organizations, researchers, and community members to address the gaps in support for lower-income community members as these cities undergo a radical transition. [59, 65] Strategies such as inclusionary zoning, developer fees, vacancy taxes, and further renter protections focusing on discrimination and harassment laws should be revisited and potentially amended. Additionally, policymakers should be working with investors and developers to acquire additional affordable units and preserve subsidies through long-term policies for rental properties serving low-income residents.

Many communities have comprehensive plans in an attempt to prevent displacement, but many have run into roadblocks disallowing them to enact these plans fully or run into issues creating a just transition for these communities. By combining or incorporating various aspects of the following strategies, communities can begin to combat displacement within their own neighborhoods.

Several communities have proposed various aspects of revitalizing communities, and in several cases these strategies have worked to combat displacement in minority communities:

These are only a few of the communities which have undergone a rapid and unjust transition as economic growth became the main goal of many metropolitan areas. Cities such as San Diego, Seattle, Jacksonville, and Miami are all undergoing gentrification and displacement to some degree, and many are at different stages. [25] To protect low-income, historically marginalized, and minority families in the US, we need to provide resources and protection to families as the cost of living has continued to outpace wage growth in many sectors. By protecting these workers, we can create a more just and equitable transition as our cities continue to evolve over time.

Dr. El’gin Avila is with the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, The University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota. He also works with Equitable Health Solutions, LLC, St. Paul, Minnesota

Dr. Ans Ifran is with the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, the George Washington University, Washington, D.C. He also works with Public Health Analytica, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Wayne Swinson is with San Francisco State University.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.