Shehata D, Al-Hadeethi B, Ibrahim Z, Al-Lami B, Qader S, Maqdasy R, Mohammad A, Nabee V, Saber S, Abdulkarim L, Hassan A, Ibrahim O, Rashid A, Abdulhamid Isa M, Ahmadi A, Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III D. The COVID-19 pandemic in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. HPHR. 2021; 29.

DOI:10.54111/0001/cc19

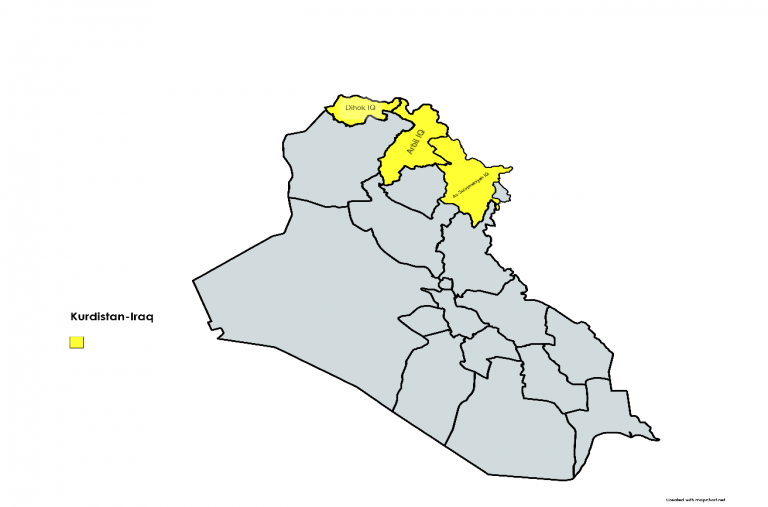

Kurdistan Region of Iraq is an autonomous region in Northern Iraq. It borders Iran to the east, Turkey to the north, and Syria to the west, along with the rest of Iraq to the south. The regional capital is Erbil. The region is officially governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) [1] .The region has four governorates, Duhok, Erbil, Sulymaniah, and Halabja as illustrated in Figure 1. With a population of 5.2 million and increasing, the region covers approximately 40,000 square kilometers. The majority of the region’s population are Kurds. In addition to that, Assyrians, Turkmen, Arabs, Armenians, Yezidis, Shabaks and Mandeans live in the region [1]. The establishment of the Kurdistan region dates back to 1970. In March 1970 an autonomy agreement was signed with Baghdad that declared autonomy for the region. Despite of the agreement, disputes remain between the central Iraqi government and the Kurdish government about predominantly Kurdish territories outside the current borders of Iraqi Kurdistan. According to that last census, 35% of the population are under the age of 15, 60% are in the active age group (16-64), and 4% are 65 and older with an estimated population growth rate of 2.54% [1].

Nearly half of KRI’s active labor force works in the public sector. Employers and employees in the private sector account for 11% of the workforce, and the remaining 35% are self-employed (18%) or daily workers (18%). Domestic workers and unpaid family workers account for the remaining 3% of the labor force. [2].

Approximately 36% of households have a monthly income of less than 500 US Dollars, over 51% have between 500 and 800 US Dollars, and 13% of households make more than 800 US dollars monthly and are considered high income families. [2].

As for poverty and low living standards, nearly 5.5 % of households were living under the poverty line. This is mainly associated with a number of socioeconomic characteristics, including the gender and age of the head of household, level of education, and working conditions. For instance, the share of low-income households is 56% for female-headed households while that of male-headed households is 33% [2].

The KRI public health system is divided into two levels: the hospital sector and the primary care sector, which is based on Primary Healthcare Centers (PHCs). Currently, there are 74 hospitals, and 847 PHCs. 249 PHCs have at least one physician present; the remaining 598 branch facilities do not [3].

Kurdistan has fewer physicians, dentists, and pharmacists per 10,000 population than most other countries in the region. The KRI has 11.1 physicians per 10,000 people which is considered insufficient compared to other countries such as Jordan which has 26, Kuwait with 18, and Egypt with 24. However, the number of nurses in Kurdistan is comparable to that of other countries [4]. Physician shortages in Kurdistan are caused by a lack of training and competencies, as well as a lack of numbers, distribution, and hours worked. Kurdistan has fewer physicians per capita than many other countries in the region and globally. Erbil and Sulaymaniyah have the most physicians (12.9 and 12.7 per 10,000 population, respectively), and Duhok has the fewest (5.3) [4].

The major contributor of the mass immigration of refugees from Syria to neighboring countries, including the KRI, and the internal displacement of Iraqis is the ongoing threat of The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which initially started in 2014 [5].

As of January 2019, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), like many neighboring and European countries, was hosting 249,293 Syrian refugees, accounting for 97% of all Syrians currently residing in Iraq. Around 38% of Syrian refugees are housed in nine camps in the three governorates of Erbil, Duhok, and Sulaymaniyah, with the remainder living elsewhere. In addition to Syrian refugees, the KRI houses formally registered refugees from Turkey (9,080), Iran (13,710), and Palestine (752). Furthermore, the KRI houses 1,123,177 Iraqi internally displaced people (IDPs) who fled Islamic State (IS)-controlled areas. Together with refugees, they account for a 28% increase in the Region’s population [5].

The KRI authorities granted Syrian refugees the right to enroll in the Region’s public schools. Primary and secondary schools were funded and run by UNICEF and UNESCO in all camps, with classes taught in Arabic and 95% of teachers being Syrian. Although Syrian refugees are permitted to work and have the right to seek employment, some professions, such as dentists, pharmacists, lawyers, and taxi drivers, face legal obstacles. This is due to refugees’ inability to provide appropriate identification or professional certificates. This is a well-documented issue as documented by the Refugee Convention [5]. As for healthcare access, nearly all camps have permanent health care centers (PHC) which provide basic health care. International organizations such as the World Health Organization and Doctors without Borders provide the health care service [5].

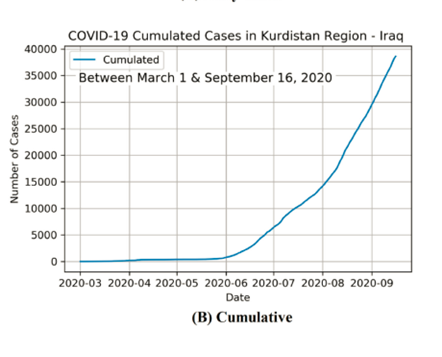

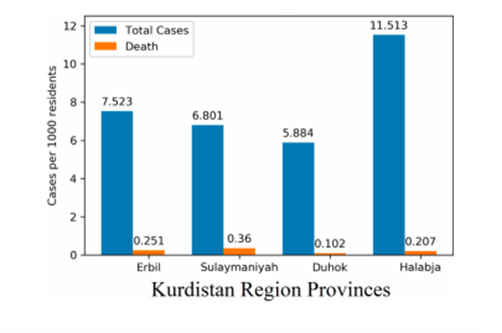

Since the novel corona virus (COVID-19) pandemic originated in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, it has been ravaging its way across the world causing a daunting global public health emergency [6]. Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) confirmed its first 4 cases on 1 March 2020, in the City of Sulaymaniyah [7]. The infected people were a family of 3 and a woman who had just returned to Kurdistan from Iran. Sulaymaniyah borders with Iran, an important source of many cases that formed the first focus of the pandemic in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Soon after, cases of COVID-19 were announced in Erbil, the capital of the region [7]. Accordingly, KRG closed all governmental organizations and the interconnected routes except for medical emergencies and security issues [7]. As of 5 May 2021, there have been 152,777 confirmed cases with 130,249 recoveries, 4,057 deaths, and 18,471 active cases. Duhok has had the highest number of confirmed cases with 58,100, followed by Erbil and Sulaymaniyah [8]. This commentary aims to discuss the current COVID-19 situation and address the challenges that the KRI has faced during this pandemic, as well as the measures taken by the government to contain the spread of the infection.

cases have been screened for the infection [9]. The KRG further conducted programs on raising awareness in the population on preventing the spread of the virus. Initially, social media platforms were utilized to deliver instructions as they are easily accessible [9]. As the number of cases increased, more extensive campaigns were launched. For instance, the KRG partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO) to launch a 2-week COVID-19 prevention and awareness campaign, which targeted 4 million people in Erbil and Duhok. The campaign aimed to convey prevention and infection control messages and highlight the importance of wearing masks, following proper hand hygiene, and maintaining physical distancing among individuals in all settings [11].

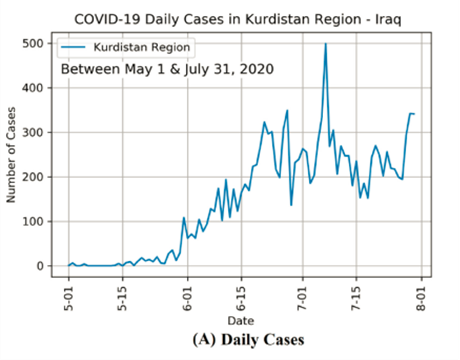

On 25 March 2020, the Iraqi government allocated almost two million US dollars along with medical equipment to the KRI as part of the region’s share of the emergency budget amid the COVID-19 pandemic [12]. Of the total $9.6 billion (2010 estimate) KRG public budget, an equivalent of over $14 million was spent to combat the spread of the new coronavirus disease. These funds were dedicated to boost the performance of health personnel, COVID-19 testing capabilities, the number of medical supplies in all provinces in the region and redesigning major public hospitals into specialized COVID-19 centers. The City of Erbil took the lead in the implementation by redesigning 4 major public hospitals into 100-bed COVID-19 centers for severe cases [13]. As the number of cases continued to rise, other cities in the region also started repurposing public hospitals into COVID-19 centers [14]. The KRG was successful in mitigating the virus in the first few months as seen in Figure 2 A and Figure 2 B, owing to community members’ adherence to the preventive measures coupled with the utilization of the above-mentioned efforts [15].

The KRG’s healthcare system faced numerous challenges before the rise of COVID-19 which were further complicated by the pandemic. Despite the aforementioned efforts, the region found itself facing various financial, medical, and social challenges. The financial turmoil had a significant impact on the response to the pandemic. In May 2020 the Federal Iraqi Government decided to suspend payments of the autonomous region’s share of the national budget caused by the plummet of global oil prices. As a region heavily dependent on oil production for economic survival, it faced a critical economic situation that turned into a crisis soon after. In response to this major budget shortfall the KRG held off on distributing salaries, then as an attempt to prevent an economic meltdown the KRG imposed dramatic cuts on salaries of public sector workers. These changes adversely affected the livelihood of the people which led to a revolt by the financially vulnerable citizens [16,17]. Public health restrictions were not followed, and mass gatherings resumed leading to a significant increase in the number of cases and a consequent overwhelming of hospitals. The unfortunate results of such actions can be seen in Figure 2 A and Figure 2 B [13,15]. This pushed the region’s economy to the brink of collapse, especially with renewed public anger and social unrest.

Inadequate medical equipment and personnel contributed to the surge in COVID-19 case numbers. The region faced shortages of proper Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), oxygen supplies, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test equipment, and laboratory reagents. Additionally, the number of health specialists in the country is insufficient, and existing health workers need to be trained in critical areas such as Infection Prevention and Control procedures [18]. Kurdish healthcare workers at the frontlines under immense pressure from long shifts, salary cuts as well as mental exhaustion embarked on a strike. This coincided with the first waves of case surge [19].

These issues were even more pronounced in refugee camp settings with most of them having small ill-equipped health centers each with a capacity of 10 beds. Kurdistan hosts about 1.5 million refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Most refugee and IDP camps are located in remote or disputed areas and are usually overpopulated. Within a short period, reports of outbreaks in camps quickly started to surface, which forced the hand of the authorities and led them to isolate many camps and limit their contact with the outside world. With large families confined to small cinder block shelters and in some cases tents, distancing in those cramped quarters was close to impossible [20]. The restrictions imposed to stop the pandemic from reaching the camps have had a devastating impact on vulnerable communities living there. Most people were already living well below the poverty line, with widespread unemployment. Following the arrival of COVID-19, those who once had jobs were forced to stay at home. This, coupled with the adverse economic situation at the time, burdened the daily lives and wellbeing of an already vulnerable community. On top of that, the restrictions have impacted the access to essential and emergency services for vulnerable population groups, including pregnant women in need of antenatal and delivery care and mothers and children in need of nutrition and immunization services. Furthermore, it impeded camp management partners to prepare camps for a potential outbreak [18].

As coronavirus vaccine doses arrived in Iraq, government officials faced pervasive vaccine reluctancy, motivated by disbelief in the virus and disappointment in the government – despite the fact that more than 3,500 people in the Kurdistan Region have died since contracting the virus [21].

Skepticism about the virus’s treatment, is widespread, fueled by medical controversies and denigrate remarks about vaccinations, to name a few examples, there have been anti-mask and anti-lockdown demonstrations since the pandemic, but vaccination cynicism predates both [21].

Countries in Europe and elsewhere are conducting mass immunization programs with the aim of vaccinating whole national populations by the end of the year. In poorer nations, such as Iraq and Kurdistan, vaccinating the whole population would take years, not months. The health ministry previously stated that the aim for this year is to vaccinate 20% of the population [21].

The first coronavirus vaccine doses arrived in Iraq on March 1. Masrour Barzani, Prime Minister 218 of the Kurdistan Region, described it as “a significant achievement in our war against COVID-19” [22]. The ministry committed a clear measure of the vaccines in the Kurdistan Region for the time being focused on for doctors, medical care laborers, twelfth-grade educators, individuals with ongoing illnesses, beneficiaries, the elderly (60 and above years of age), the security powers, and Peshmerga forces [23]. Kurdistan Regional Government’s Ministry of Health had launched a pre-registration website for applying for appointments to receive jabs of COVID-19 vaccination on April 4, residents in the KRG should enlist online to be qualified for the three accessible vaccines, including Pfizer, the Chinese Sinopharm, and the UK-Swedish Oxford-AstraZeneca pokes [23].

The KRG has received tens of thousands of additional COVID-19 vaccine doses. Masrour Barzani, Prime Minister of the Kurdistan Region of Northern Iraq, declared that 43,800 doses of the AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine had arrived in the autonomous region of northern Iraq. With collecting 5,000 doses of China’s Sinopharm vaccine, the KRG started distributing vaccine doses 230 to health care staff in March 2021 [22]. The first batch of the American-German vaccine arrived 231 in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region in early April (Pfizer), of which the Region received over 2,000 doses as part of its share from the 50,000 sent to the federal government [23].

So far, 98,810 vaccinations have arrived in the Kurdistan Region as part of the national vaccination scheme, with more than 70% of those used to vaccinate the population [22].

Kurdistan’s current outbreak status shows that the pandemic has crippled the region’s health system, economy, and overall livelihood. The accelerated spread of the virus, the economic crisis, and people’s response caught the region off guard, this made it harder for the government to fight for keeping its sinking healthcare system afloat. Despite all the efforts and strategies that have been employed, multiple issues ranging from the economic collapse to the public’s anger are making the containment of the pandemic unachievable. The government needs to introduce new solutions to combat the economic crisis by reaching some of the opportunities to access resources in the form of contributions from corporate foundations loans, debt relieve schemes and other financial mechanisms as well as offer support to frontline doctors by providing adequate PPEs and expanding the workforce to decrease the workload.

Dina Shehata is a 5th year medical student from the Kurdistan region of Iraq studying at Hawler Medical University/ College of medicine.

Ban Tareq Al-Hadeethi is a motivated 5th stage medical student eager to learn and advocate for public health and research.

Zheen Bahaddin Ibrahim is a junior medical doctor in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. He is also an aspiring medical researcher and academic. His main interests are psychiatry, medical education, and public health.

As a medical student at Hawler Medical University, I have always been interested in different aspects of the medical field, especially the research part of it. It allows me to search for answers that satisfy my never ending curiosity, and helps me see the bigger picture.

San Mohammed Qader is a medical student at HMU in Erbil Iraq with a passion for research and continuing medical education.

Reveen Maqdasy is a 5th year medical student, interested in internal medicine and technology in medicine.

Aya Nasih Mohammad is a 3rd stage medical student at Hawler Medical University, IFMSA – Kurdistan, who is passionate about research.

Van Fadhil Nabee a senior year medical student at IFMSA – Kurdistan.

Awaz Mebashar Hassan, MBChB, is a student at IFMSA Kurdistan, and is interested in medical reesearch.

Othman Ibrahim is a medical student at HMU and a Ifmsa-Kurdistan member for 3 years. He is a graduate of Qalla College for Gifted Students.

Alaa Mohammed Rashid is a passionate and enthusiastic learner with Hawler Medical University, College of Medicine and IFMSA-Kurdistan, College of Medicine.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.