Chandnani A, Coburn W, Fichtner J, Hakimi A, Huang J, Liu T, Neilson T, Su M, Tran W, Coors M. Mental health and substance use in Colorado healthcare and graduate students during COVID-19: a mixed-methods investigation.HPHR. 2021; 29.

DOI:10.54111/0001/cc10

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact mental health by exacerbating anxiety, fear, and substance use worldwide. Several studies have demonstrated increased substance use and declining mental health in students abroad, but no investigation has assessed the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on mental health and substance use in graduate and healthcare students in the United States.

Researchers sought to quantify and qualify the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on Colorado graduate and healthcare students’ mental health and substance use, hypothesizing that greater COVID-19-related fear would correlate with higher substance use rates across metrics.

Investigators utilized an online, institutionally-distributed, mixed-methods survey to assess quantitative and qualitative changes in various mental health metrics and substance use in Colorado healthcare and graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic from June 2020 to February 2021. An augmented Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) academic survey served as the primary data collection vessel.

Students who reported higher levels of depression, exhaustion, loneliness, nervousness, and anger had significantly higher FCV-19S scores. Higher FCV-S19 scores were also significantly associated with increased levels of alcohol consumption, binge drinking, and cannabis use. Qualitative analysis elucidated recurring themes regarding use frequency, substances used, and the reasons underlying use. Further qualitative analysis revealed three common student concerns: worries regarding the length of the pandemic, its social impact, and educational/financial impact.

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected the well-being of Colorado healthcare and graduate students, directly increasing substance use while simultaneously exacerbating feelings of fear, anxiety, and helplessness.

The COVID-19 pandemic has killed more than 2.5 million people to date and presented serious challenges to the health and well-being of people around the world. 1 Studies from COVID-19 and earlier pandemics demonstrate the negative impacts on mental health caused by increased levels of anxiety and fear, among other mediators.2-6 Negative economic, social, and medical consequences of the pandemic—combined with epidemiologic mitigation strategies such as “stay-at-home” orders—have only worsened COVID-19-related mental health outcomes.7-9

Healthcare students are at increased baseline risk for anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation10-17. Medical students in particular have been identified as an at-risk group for high rates of substance abuse18-20 with one study demonstrating that up to 32% of students meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence19. Further studies have indicated that healthcare students experiment with atypical drugs at higher rates than other populations as a coping mechanism21-23. Although the mental health challenges faced by healthcare students are well documented, little evidence is currently available regarding the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on emotional well-being and substance abuse.

Acute fear can be a valuable adaptive behavioral mechanism. However, chronic fear can hasten development of numerous psychiatric disorders in addition to exacerbating pre-existing ones. In the United States, research has shown that areas reporting the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases also report higher levels of COVID-19 fear. 30

One previously validated metric that assesses COVID fear is the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), a 7-item scale that measures the severity of coronavirus-related fear on a 30-point scale (ranging from 5 to 35). Since its initial development,31 the FCV-19S measurement has been validated in diverse populations worldwide32-34—including in U.S. college-aged adults. 35

Past research consistently reports high levels of COVID-19 fear among university students,36 nursing students,37 medical students,38-40 and other allied health professional students.27-29, 41 Significant evidence demonstrates negative mental health impacts of COVID-19 and increased substance use among graduate healthcare students abroad.41-44 However, there is minimal investigation into the effects of COVID-19 on substance use in American healthcare and graduate students.

This mixed-methods study investigates the intersection of self-reported mental health and substance use during COVID-19 in graduate-level healthcare and social work students in Colorado via an augmented version of the FCV-19S. Specifically, this study quantifies the relationships between substance use and COVID-19 fear score across different academic programs, genders, and clinical experience treating COVID-19 patients. Researchers also employed qualitative methods to identify potential drivers of these relationships. Researchers hypothesized that healthcare and graduate students with higher FCV-19S scores would correlate with higher substance use rates across all demographics, with minimal differences across study variables (e.g., gender, program of study, clinical experience).

This investigation assesses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, fear, and substance use in graduate-level healthcare and social work students from June 2020 through February 2021. Researchers surveyed students from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center, including the Schools of Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Physical Therapy, Public Health, and the Physician Assistant and Graduate Program, as well as the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #20-1297) approved this study. Designers incorporated informed consent into the instrument and required it from respondents prior to starting the survey.

A Qualtrics web-based questionnaire was distributed to students via their school emails. Researchers adapted this survey from the Ben Gurion University RADAR Center’s survey that investigated patterns of substance use during lockdowns, using previously validated metrics and allowing for more accurate comparison against similar studies. The questionnaire incorporated the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) compiled by Ahorsu et al., 31 which evaluates seven items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for a total possible score of 35, with higher scores corresponding to greater fear. Researchers selected this already-validated survey and corresponding metrics for prompt distribution to students at the beginning of the pandemic. The survey asked general demographic questions followed by queries on anxiety levels, emotional well-being, and types of substance use pre- and post-COVID-19; other confounding factors were not identified or accounted for in the survey collection. The survey also contained a free-response section for students to discuss contributors to self-reported fear and stress as well as substance use patterns. The complete questionnaire is included in the Appendix.

Each academic program disseminated the survey to its students approximately once per month, though the survey was coded such that each student could only respond once. All data was anonymously entered and analyzed. To increase response rates, researchers promoted a chance to win two $25 Amazon gift cards through a post-survey raffle.

Researchers conducted descriptive statistics using frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Statisticians summarized continuous data with means and standard deviations and medians with minimum and maximum values (Appendix Table 1). They further analyzed FCV-19S summary statistics for skewness and kurtosis to ensure statistical reliability. Independent t-tests assessed for differences in FCV-19S scores based on paired categorical variables (e.g., answering “yes” or “no” for increased depression). The O’Brien, Brown-Forsythe, Levene, and Bartlett tests assessed the equal variance assumption and Welch’s t-test assessed unequal variances. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests analyzed differences in FCV-19S scores based on multi-category variables (e.g., Academic Program). Pearson’s chi-square tests assessed for differences in categorical response rates (e.g., answering “yes” or “no” for increased alcohol intake). Quantitative analysis used JMP Pro 14 at α=0.05 significance level. Of note, the study instrument failed to account for confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status, prior mental health diagnoses, or other potentially confounding variables. As such, researchers were unable to statistically modify results to account for such factors.

Researchers utilized grounded-theory methodology to review the free response questions and developed individual code books through ATLAS.ti. After individual review, the researchers discussed and recorded common themes from students’ free responses.

Survey respondents had the opportunity to provide short written responses to two main topics: “If you feel excess stress or anxiety from the COVID-19 pandemic, please tell us about your condition,” and “If you have used alcohol and/or other substances to reduce COVID-19 stress or anxiety, please tell us about your pattern of use.” Researchers extracted two primary themes and three respective sub themes from the free-response data. These were coded as follows for the qualitative analysis: (1) concerns surrounding COVID-19 and (2) patterns of substance use. Subcodes were identified based on frequency of common themes.

Investigators enrolled 918 students from nine academic programs at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work. Seven respondents indicated that they were not enrolled in Spring 2020 graduate-level courses, and their responses were excluded from the final analysis.

The survey sample consisted of professional healthcare students with an average age of 27.73 years and standard deviation of 5.27 years (Table 1). Roughly three-quarters (74.67%) of respondents identified as female, 24.22% as male, and 1.10% as sexual minorities (non-binary or transgender). More than 70% (70.56%) of survey respondents self-identified as White, 17.86% as Asian, 7.61% as Hispanic or Latino, and 2.54% as Black or African American. Over half of respondents (51.59%) identified as “not religious,” 30.63% as “somewhat religious,” and 17.78% as “religious or very religious.” Notably, only 11.64% of respondents reported clinical experience treating COVID-19 patients. More than 74% (74.09%) of 911 included surveys were fully completed—and of the 25.91% of incomplete surveys the median completion percentage was 94%. Average response rates were 26.31% (ranging from 9.24% for public health to 50.00% for nursing) based on Fall 2018 enrollment data (n=5202), adjusted to remove one cohort from each program (adjusted to n=3462) as the graduating students from each cohort did not get an opportunity to fill out the survey.

n (%) | |

Age | |

Mean ± SD | 27.73 ± 5.27 |

Median, Range | 26, 20-56 |

Gender | |

Female | 678 (74.67) |

Male | 220 (24.22) |

Non-binary or transgender | 10 (1.09) |

Ethnicity | |

White | 640 (70.56) |

Asian | 162 (17.86) |

Hispanic or Latino | 69 (7.61) |

Black or African American | 23 (2.54) |

American Indian or Alaska Native | 8 (0.88) |

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 5 (0.55) |

Strength of religious identification | |

Not religious | 470 (51.59) |

Somewhat religious | 279 (30.63) |

Religious/very religious | 162 (17.78) |

Academic Program | |

Medicine | 205 (22.50) |

Dentistry | 161 (17.67) |

Graduate School | 132 (14.49) |

Nursing | 125 (13.72) |

Social Work | 119 (13.06) |

Pharmacy | 87 (9.55) |

Physician Assistant | 31 (3.40) |

Physical Therapy | 28 (3.07) |

Public Health | 23 (2.53) |

Clinical experience treating COVID-19 patients | |

No | 805 (88.36) |

Yes | 106 (11.64) |

Fully completed survey | |

Yes | 675 (74.10) |

No | 236 (25.91) |

Percent progress of uncompleted surveys | |

Mean ± SD | 81.64 ± 1.38 |

Median, Range | 94, 0-95 |

Nearly six in ten (58.66%) students reported feeling more depressed, 67.55% more exhausted, 66.74% more lonely, 65.47% more nervous, and 50.23% more angry due to COVID-19 (Table 2). Those who reported feeling more depressed, exhausted, lonely, nervous, or angry all reported higher mean FCV-19S scores that reached statistical significance relative to those who denied such feelings (p<0.0001).

“During the last 3 months or so, because of COVID-19, have you felt more…?” | COVID-19 Fear Value, Mean ± SD | dF | t | n (%) |

Depressed*** | 829.63 | 11.60 | ||

Yes | 18.24 ± 5.16 | 508 (58.66) | ||

No | 14.44 ± 4.45 | 358 (41.34) | ||

Exhausted*** | 686.54 | 11.64 | ||

Yes | 17.92 ± 5.25 | 585 (67.55) | ||

No | 14.10 ± 4.12 | 281 (32.45) | ||

Lonely*** | 864 | 8.01 | ||

Yes | 17.65 ± 5.16 | 578 (66.74) | ||

No | 14.73 ± 4.82 | 288 (33.26) | ||

Nervous*** | 678.84 | 16.32 | ||

Yes | 18.48 ± 4.81 | 567 (65.47) | ||

No | 13.31 ± 4.22 | 299 (34.53) | ||

Angry*** | 842.01 | 8.28 | ||

Yes | 18.48 ± 4.81 | 435 (50.23) | ||

No | 13.31 ± 4.22 | 431 (49.77) |

*** Indicates intragroup difference with p < 0.0001.

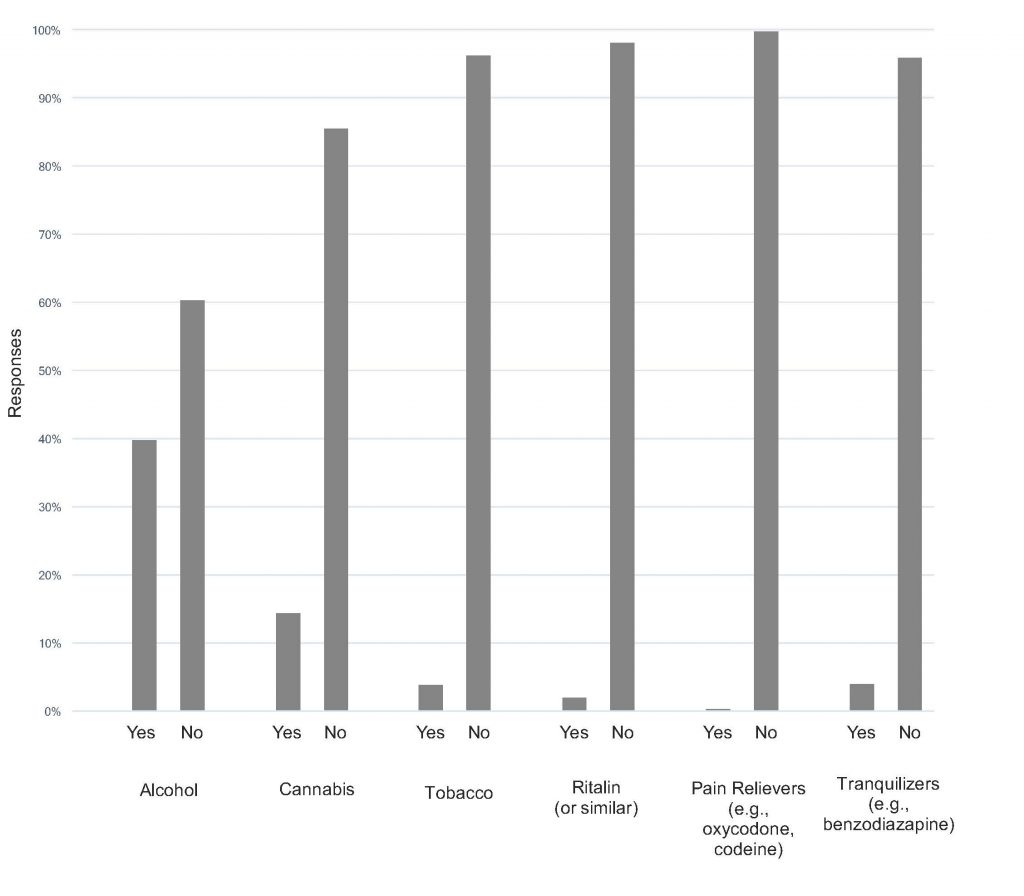

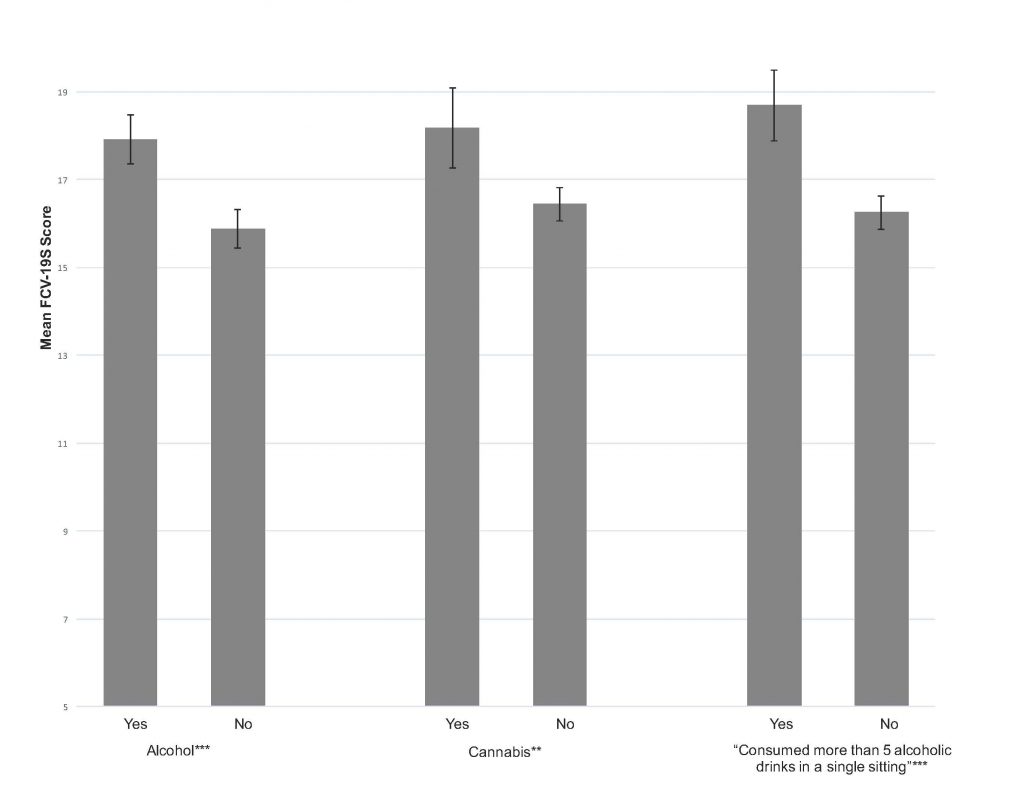

Nearly 40% (39.72%) of respondents reported increased alcohol intake, 17.72% reported consuming at least five alcoholic drinks on one occasion, and 14.44% reported increased cannabis use due to COVID-19 (Figure 1; Appendix Table 2). Moreover, these activities were associated with statistically significantly higher FCV-19S scores of p<0.0001, p<0.0001, and p=0.0003, respectively (Figure 2). Of the population that reported using alcohol less than once per month prior to COVID-19, 10.00% reported using more alcohol because of COVID-19 (Appendix Table 3). Similarly, 4.22% of respondents who reported using cannabis less than once per month prior to COVID-19 reported using more cannabis because of COVID-19.

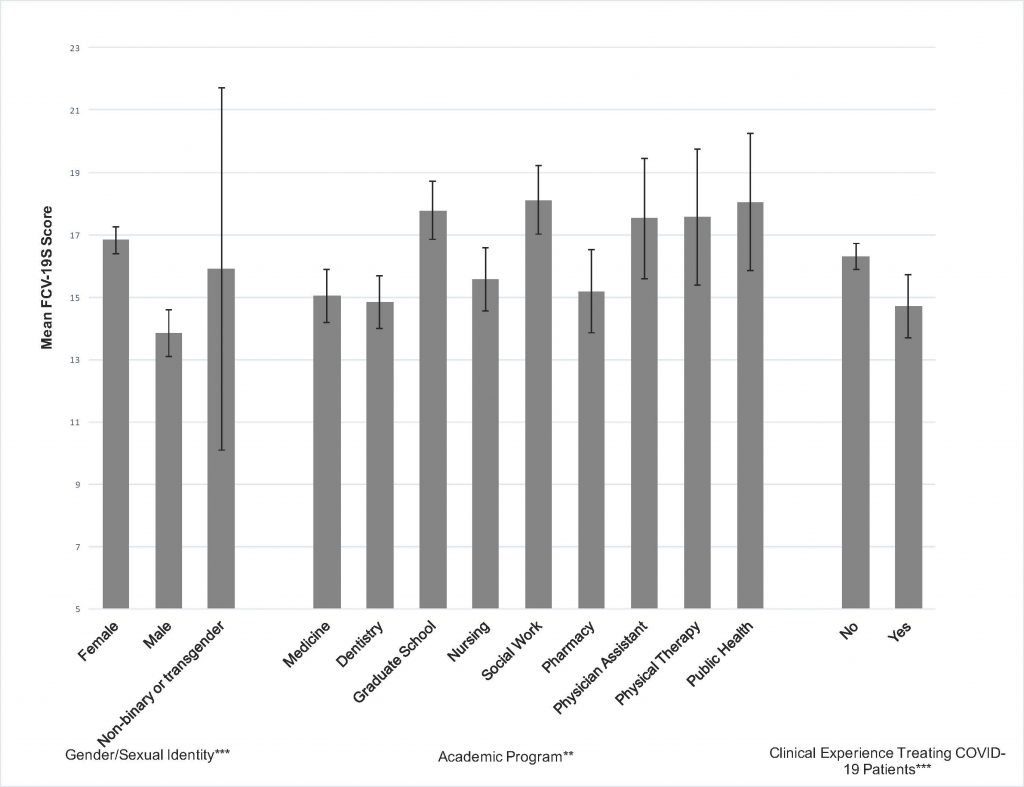

Figure 3 displays the mean FCV-19S score by gender, school program, and clinical experience in treating COVID-19. Gender correlated with a significant difference in mean FCV-19S scores; women demonstrated mean scores of 16.83 ± 5.80 and men reported mean scores of 13.82 ± 5.66. Of note, students identifying as transgender/nonbinary did not provide adequate response rates for FCV-19S/substance use analysis.

Dental, medical, and pharmacy students scored the lowest on the FCV-19S, with mean scores and standard deviations of 14.82 ± 5.46, 15.04 ± 6.19, and 15.17 ± 6.26, respectively. Social work and public health students scored the highest on the FCV-19S, with mean scores of 18.11 ± 6.05 and 18.04 ± 5.10, respectively. Interestingly, clinical experience with treating COVID-19 patients correlated with significantly lower mean FCV-19S scores (14.70 ± 5.26) relative to those without clinical experience (16.31 ± 6.02; p<0.0001). Finally, students who reported increased alcohol use, cannabis use, and binge drinking all reported higher mean FCV-19S scores in a statistically significant fashion compared to respondents who denied such increased use.

Students expressed three main qualitative themes regarding COVID-19 concerns: the duration of the pandemic, its impact on education/finances, and its social impact. Deductive coding elucidated three additional themes in response to the substance use question: frequency of use, substances used, and reasons for change. Table 3 presents a full list of codes and subcodes with direct quotes from students.

Common student concerns included the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic’s duration, family health issues, asymptomatic spread, and media and government responses. Along with fears of family members contracting the virus, many participants indicated frustration with the lack of urgency shown by the general community, citing lack of social distancing/mask wearing and nonchalant attitudes towards the pandemic as issues of key concern. Many also expressed unease regarding perceived delayed responses by the governmental officials who handled the pandemic in its early phases. Respondents specifically felt that misinformation became pervasive during COVID-19 and that an overall “politicization” of the pandemic occurred.

Student responses highlighted a second common theme––concerns regarding the pandemic’s impact on their educational training, current finances, and future job prospects. Some noted a decrease in motivation and perceived a decline in lecture quality regarding online coursework. Due to decreased in-person clinical experiences, many worried that they would lack the appropriate training upon graduation. Job loss and diminished career prospects also produced significant financial concern in participants. Some questioned the value of continuing their academic training as they balanced current financial burdens with a decline in future job prospects.

Finally, many respondents reported adverse impacts on their social relationships and well-being. Students acknowledged the importance of maintaining social distancing protocols but struggled to reconcile this against needs for social interaction. Students cited this dilemma as the cause of increasing depression and anxiety.

Students consistently reported increased substance use frequency. A majority of participants designated alcohol as their primary pandemic coping substance, followed closely by cannabis. Nicotine, stimulants, and sedatives were also mentioned, though at a lower rate. Notably, participants reported evolving patterns of substance use; some became first-time users during the pandemic, while others progressed to usage daily or multiple times per day. Several participants with histories of substance abuse shared that they relapsed during the pandemic. Many respondents reportedly utilized substances to cope, de-stress, reduce anxiety, decrease boredom, aid in sleep, and occupy free time. However, it is worth noting that a small number of students reported no change or even decreased their frequency of substance use during the pandemic.

Code | Subcode | Participant Examples |

Concerns Surrounding COVID-19 | Length of the Pandemic: ¨ Health ¨ Asymptomatic Spread ¨ Is there an end? ¨ Long-term Impacts ¨ Poor government response ¨ Misinformation ¨ Lack of Urgency Impact on Education/Finance: ¨ Rotations/Clinical Training ¨ Decreased Quality ¨ Job Instability Social Impact: ¨ Loneliness ¨ Inability to travel ¨ Relationships | · “I worry for my family members (parents, grandparents, aunts/uncles) getting sick because they are all high risk.” · “Concerned about asymptomatic spread of COVID-19 and unintentional harm of others.” · “I believe my education is sub-par from what it used to be.” · “My concerns are mostly about future prospects and careers as a nurse given I have not had the standard level of clinical experiences.” · “Job-related financial concerns as I lost my job and isolation impacting mental health and relationships” · “It feels like this will never end and I can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel which makes my depression worse.” · “[The pandemic] will be prolonged because government officials are not treating it with the highest priority.” · “Our society is not taking the pandemic seriously and are selfishly ignoring masks and social distancing.” · “Hard to stay in contact with friends or go traveling to see family.” |

Patterns of Substance Use | Frequency: ¨ Increased ¨ Relapse Substances: ¨ Alcohol ¨ Cannabis ¨ Nicotine ¨ Sedatives ¨ Stimulants Reasons for Changes: ¨ Boredom ¨ Destressing ¨ Sleep Aid |

· “During quarantine, I found myself drinking far more than usual. As someone who…suffers from depression and anxiety, my symptoms have intensified, and I felt hopeless…” · “I have been drinking more frequently to “destress” and even turned to medical cannabis in order to sleep some nights.” · “I mainly smoke weed to help me get through the loneliness and to make work more fun. Xanax has also helped me forget about stuff.” · “I’m an alcoholic and relapsed a month ago.” · “My Adderall use has increased because focusing at home is more difficult than in class.” |

Global trends during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate worsening mental health across populations,6, 8, 9, 24, 25, 29, 30, 33, 45-51 and increasing consumption of alcohol, cannabis, and other recreational substances.52 This investigation demonstrates that American healthcare and graduate students are no exception to these patterns, as more than half of study enrollees report worsening feelings of depression, exhaustion, loneliness, nervousness, and anger. This is unsurprising, as students are burdened with academic pressures and career decisions in addition to the struggles faced by the general public. This study elucidates several significant associations in this population: (1) students with higher fear of COVID-19 had significantly increased substance use, (2) students with direct clinical exposure to COVID-19 had significantly lower fear, and (3) women reported significantly higher fear than men.

Qualitative data regarding reasons for use parallels current literature investigating substance use as a coping mechanism.53, 54 The results of this study demonstrate significant increases in reported alcohol use and a significant association of alcohol use with higher FCV-19S scores (17.92 compared to 15.88). However, it is unclear from the present study whether fear drives alcohol use or whether alcohol (or other substance) use predisposes students to higher levels of fear.55, 56 Excess consumption of addictive substances can potentially worsen existing mental health problems.57 This is particularly worrisome in students seeking graduate healthcare degrees, as poor mental health portends both declines in academic performance and reduced completion of academic programs.43

The impact of COVID-19 on cannabis use remains a topic of debate. Vanderbruggen et al. note no significant changes in cannabis use in Belgium,58 while Imtiaz et al. report increased cannabis usage among prior users.59 The results of this study demonstrate a statistically significant increase in cannabis usage which more closely mimics findings from the latter. Given the legality of recreational cannabis in Colorado, researchers anticipated significantly greater cannabis use––making the relatively greater increase of alcohol (39.72%) use compared to cannabis use (14.44%) notable. Such differences may be explained by several factors, including ease of access, cultural acceptance, user preference, and school-mandated drug tests. Though cannabis use has been reported as a coping mechanism during times of stress, numerous studies cite that variation in motives impact usage rates.60-62 Associations between cannabis use and increased anxiety may also reduce its popularity as a coping substance. However, the cannabis-anxiety relationship remains a topic of debate.63, 64

Although only 11.64% of respondents indicated experience treating COVID-19 patients, the average FCV-19S score in this group was lower (14.70 vs. 16.31) in a statistically significant fashion compared to students who reported no experience treating COVID-19 patients (Appendix Table 6). This outcome aligns with classical findings that suggest that increased exposure to fear stimuli can result in lower levels of overall fear65-69. This study suggests that a critical component of COVID-19 fear centers around fear of the unknown, and that lower FCV-19S scores in healthcare workers may reflect acclimatization of healthcare workers to increased baseline levels of fear in clinical settings. The results indicate that mean FCV-19S scores were lower among medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students, and higher among physician assistant, physical therapy, public health, and other graduate students. These findings could be due to a variety of differences, including: program-specific structural differences, availability of student support and social resources, and pre-existing demographic differences.

Regarding gender, study results show statistically significant higher mean FCV-19S scores among females compared to males, but with no accompanying difference in substance use changes. This suggests that increased drug use could be associated with other factors related to COVID-19 or higher baseline substance use among males.

This study has several limitations. The study design was adapted from a previously validated survey first developed in Israel and used around the world. However, it has been utilized less frequently in the United States and was used “as-is” for expediency. The survey’s response rate of 26.31% may impact generalizability. Additionally, because this survey only targeted students on the Anschutz Medical Campus and social work students from the University of Denver, these findings may not be representative of healthcare students at other schools or, indeed, in other countries. Researchers also did not evaluate the socioeconomic status of respondents or include other potentially confounding variables, such as previous mental health diagnoses, that may predispose vulnerable individuals to declines in mental health and increased rates of substance use. Finally, the results of this study could potentially be influenced by recall and volunteer bias in self-reporting; the survey relied on respondents’ recollections of substance use prior to the pandemic. As such, respondents who were more afraid of, or impacted by, COVID-19 may have volunteered at higher rates to complete the survey and expressed greater substance use rates compared to those who did not.

The strengths of this study include capturing responses from a variety of healthcare students on a large medical campus––including medical, dental, pharmacy, nursing, physical therapy, public health, and physician assistant students—as well as social work students from the University of Denver. This study is among the first to evaluate U.S. healthcare students’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic through the lens of substance use and emotional well-being. Nearly two-thirds of healthcare students surveyed report increased rates of negative emotions due to the pandemic, and high FCV-19S scores indicate a high prevalence of fear and anxiety surrounding COVID-19.

Future directions for research include expanding its scope to cover healthcare programs at multiple graduate and undergraduate institutions, both in the United States and abroad, to allow for greater generalizability. Further studies should investigate the temporality of COVID-19-associated substance use, the development of substance use disorders in students, and expand to include current/prior mental health diagnoses. Finally, understanding the changes in fear levels pre- and post-clinical exposure to COVID-19 serves an important role in understanding the “fear of the unknown” and may illuminate mechanisms of professional adaptation necessary for healthcare workers in times of increased stress.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Richard Isralowitz, Director and Professor Emeritus at the Ben Gurion University of the Negev – Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center, for inspiration and access to the survey instrument.

69. Singewald N, Schmuckermair C, Whittle N, Holmes A, Ressler KJ. Pharmacology of cognitive enhancers for exposure-based therapy of fear, anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. May 2015;149:150-90. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.004

Your answers to the following questions will provide useful information for planning and promoting healthy behavior during difficult times. Participation in this survey is voluntary. A donation of $1 will be made to a COVID-19 relief fund for each completed survey received. Anonymity is promised. Completion of the following survey confirms your consent for participation. Please answer each question in the best way possible.

Q1 Were you enrolled in classes at CU Anschutz or at the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work during the Spring 2020 semester?

Yes

No

Q2 What academic program are you currently a member of? (select one)

School of Medicine

School of Dentistry

School of Pharmacy

College of Nursing

Physical Therapy

School of Public Health

Graduate School

Physician Assistant Program

School of Social Work

Q3 Coronavirus (COVID-19) affects our health and well-being including the possibility that substances are used to cope with present conditions.

Q4 What gender do you identify with?

Male

Female

Transgender

If neither of these fit, include one that does________________________________________________

Q5 What is your age? (years)

Age (1)

▼ 18 (1) … 70 (53)

Q6 Please select your ethnicity:

American Indian or Alaska Native

Asian

Black or African American

Hispanic or Latino

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

White

Q7 Are you? (check one)

Not religious

Somewhat religious

Religious / very religious

Q8 Do you have clinical experience with treating COVID-19 patients?

Yes

No

Q9 On a scale from 1(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), please respond to the following statements based on COVID-19 conditions during the LAST 3 MONTHS or so:

Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neither agree nor disagree (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly agree (5) | ||

I am afraid of COVID-19 (1) | ||||||

It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19 (2) | ||||||

My hands become clammy when I think about COVID-19 (3) | ||||||

I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19 (4) | ||||||

When watching news and stories about COVID-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious (5) | ||||||

I cannot sleep because I worry about getting COVID-19 (6) | ||||||

My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting COVID-19 (7) | ||||||

I fear my university studies will be negatively affected by COVID-19 (8) | ||||||

I am experiencing excess stress and anxiety due to the impact of COVID-19 on my social and family life (9) | ||||||

Q10 BEFORE COVID-19, did you use any of the following substances at least once a month?

Yes (1) | No (2) | |

Cigarettes (and other tobacco products) (1) | ||

alcohol (e.g. beer, wine, hard liquor) (2) | ||

cannabis (3) | ||

medical cannabis (4) | ||

Ritalin (or similar) (5) | ||

pain relievers (e.g., oxycodone, codeine) (6) | ||

sedatives/tranquilizers (e.g., benzodiazepine) (7) |

Q11 BECAUSE of COVID-19, during the LAST 3 MONTHS, have you used any of the following substances more than usual?

Yes (1) | No (2) | |

Cigarettes (and other tobacco products) (1) | ||

alcohol (e.g. beer, wine, hard liquor) (2) | ||

cannabis (3) | ||

medical cannabis (4) | ||

Ritalin (or similar) (5) | ||

pain relievers (e.g. oxycodone, codeine) (6) | ||

sedatives/tranquilizers (e.g. benzodiazepine) (7) |

Q12 During the LAST 3 MONTHS, have you had 5 or more alcoholic drinks during one drinking occasion/event because of COVID-19 related impacts on your life?

Yes

No

Q13 If you feel excess stress or anxiety due to COVID-19, please tell us about your condition.

Q14 If you have used alcohol and/or other substances to reduce COVID-19 stress or anxiety please tell us about your pattern of use (e.g. what substance, how much, and how often).

Q15 What other concerns do you have about COVID-19?

Q16 During the LAST 3 MONTHS or so, because of COVID-19, have you felt MORE:

Yes (4) | No (5) | |

Depressed (1) | ||

Exhausted (2) | ||

Lonely (3) | ||

Nervous (4) | ||

Angry (5) |

______________________________________________________________

Thank you for your cooperation and stay well, please.

Our study is also hosting several focus groups, discussing COVID-19 coping methods, stress, and anxiety. These focus groups will be a single session, with 1-1.5 hours of discussion. If you are interested in participating, please enter your email below and a member of our team will be in contact with you. Participation is voluntary.

________________________________________________________________

Thank you for participating in our study. If you would like to enter a raffle for a $25 Amazon gift card, copy and paste the link below:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScPG005vxm9Mw6cwVFIv5VfktTTppnQGXzOwMAYPI035BRbVg/viewform

“Based on COVID-19 conditions during the last 3 months or so…” |

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Minimum value selection, n (%) | Maximum value selection, n (%) |

“I am afraid of COVID-19” | 3.30 ± 1.08 | -0.54 | -0.61 | 58 (6.55) | 74 (8.36) |

“It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19” | 2.73 ± 1.13 | 0.09 | -1.02 | 130 (14.69) | 36 (4.07) |

“My hands become clammy when I think about COVID-19” | 1.70 ± 0.77 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 124 (14.01) | 3 (0.34) |

“I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19” | 2.22 ± 1.09 | 0.66 | -0.44 | 82 (9.27) | 22 (2.49) |

“When watching news and stories about COVID-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious” | 3.14 ± 1.20 | -0.37 | -1.02 | 65 (7.34) | 79 (8.93) |

“I cannot sleep because I worry about getting COVID-19” | 1.73 ± 0.86 | 1.24 | 1.34 | 118 (13.33) | 6 (0.68) |

“My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting COVID-19” | 1.85 ± 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.45 | 114 (12.88) | 8 (0.90) |

“Because of COVID-19, during the last three months, have you used any of the following substances more than usual?” | COVID-19 Fear Value, Mean ± SD | dF | t | n (%) |

Alcohol*** |

| 864 | 5.72 |

|

Yes | 17.92 ± 5.25 |

|

| 342 (39.49) |

No | 15.88 ± 5.06 |

|

| 524 (60.51) |

Cannabis** |

| 862 | 3.45 |

|

Yes | 18.18 ± 5.14 |

|

| 124 (14.35) |

No | 16.44 ± 5.21 |

|

| 740 (85.64) |

“Consumed more than 5 alcoholic drinks in a single sitting”*** |

| 867 | 5.36 |

|

Yes | 18.69 ± 5.09 |

|

| 154 (17.72) |

No | 16.25 ± 5.15 |

|

| 715 (82.28) |

** Indicates intragroup difference with p < 0.01.

*** Indicates intragroup difference with p < 0.0001.

“Because of COVID-19, during the last 3 months or so, have you…?” | n (%) |

“Used cannabis more than usual” |

|

Yes | 29 (4.22) |

No | 658 (95.78) |

“Used alcohol more than usual” |

|

Yes | 21 (10.00) |

No | 180 (90.00) |

“Because of COVID-19, during the last three months, have you used any of the following substances more than usual?” | Total n (%) | Male n (%) | Female n (%) |

Cannabis |

|

|

|

Yes | 124 (14.44) | 27 (13.11) | 92 (14.35) |

No | 735 (85.57) | 179 (86.89) | 549 (85.65) |

Alcohol |

|

|

|

Yes | 342 (39.72) | 76 (36.89) | 263 (40.90) |

No | 519 (60.28) | 130 (63.11) | 380 (59.1) |

Tobacco |

|

|

|

Yes | 32 (96.27) | 10 (4.88) | 22 (3.43) |

No | 826 (3.73) | 195 (95.12) | 619 (96.57) |

Ritalin (or similar) |

|

|

|

Yes | 17 (1.98) | 4 (1.95) | 12 (1.88) |

No | 840 (98.02) | 201 (98.05) | 628 (98.13) |

Pain relievers (e.g., oxycodone, codeine) |

|

|

|

Yes | 2 (0.23) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.31) |

No | 854 (99.77) | 206 (100.00) | 636 (99.69) |

Tranquilizers (e.g., benzodiazepine) |

|

|

|

Yes | 35 (4.08) | 7 (3.43) | 27 (4.20) |

No | 824 (95.92) | 197 (96.57) | 616 (95.80) |

*None of the above substances exhibited statistically significant use patterns between males and females using Pearson’s chi-squared test

Variable | COVID-19 Fear Value, Mean ± SD |

Gender |

|

Female | 16.83 ± 5.80 |

Male | 13.82 ± 5.66 |

Non-binary or transgender | 15.90 ± 8.12 |

Academic Program |

|

Medicine | 15.04 ± 6.19 |

Dentistry | 14.82 ± 5.46 |

Graduate School | 17.77 ± 5.43 |

Nursing | 15.57 ± 5.83 |

Social Work | 18.11 ± 6.05 |

Pharmacy | 15.17 ± 6.26 |

Physician Assistant | 17.52 ± 5.28 |

Physical Therapy | 17.57 ± 5.62 |

Public Health | 18.04 ± 5.10 |

Clinical experience treating COVID-19 patients |

|

No | 16.31 ± 6.02 |

Yes | 14.70 ± 5.26 |

Used alcohol more than usual? |

|

Yes | 17.92 ± 5.25 |

No | 15.88 ± 5.06 |

Used cannabis more than usual? |

|

Yes | 18.18 ± 5.14 |

No | 16.44 ± 5.21 |

Consumed more than 5 alcoholic drinks in one sitting because of COVID-19 related impacts on your life more than usual? |

|

Yes | 18.69 ± 5.09 |

No | 16.25 ± 5.15 |

Arun Chandnani is a current second year medical student at University of Colorado School of Medicine. He received a BS in Chemical Engineering from the University of Illinois.

William Coburn is a third-year medical student at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. In his free time, he enjoys running, photography, making ceramics, and traveling.

Justin Fichtner is a medical student at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. In his free time he enjoys cooking, hiking, playing softball or volleyball, and spending time with his fiancé.

Ali Hakimi is a second year medical student at the CU School of Medicine and his research interests include the psychiatric impacts of surgery, medical education, depression and substance use.

Jin Huang is a medical student at the University of Colorado interested in OB/GYN.

Ian T. Liu is currently a medical student at the University of Colorado, and is interested in healthcare and its intersection with law, policy, and public health.

Taylor Neilson is currently a second-year medical student at the University of Colorado and received a BS in Animal Science and Biochemistry from Oklahoma State University.

Malcolm Su is a medical student who is interested in the field of psychiatry.

Wesley Tran is a current medical student at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. He is interested in becoming a pediatric surgeon with the goal of aiding future underserved patients and their families.

Research interests pursued by Dr. Coors include the ethics of human genetic modification, informed consent in genomic research, and the use of genomic information in behavioral genetics. As the Director of Research Ethics for the Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Institute, she is directly involved in research ethics consultation and cross disciplinary ethics education. Coors is an Affiliate member of the University of Colorado Division of Substance Dependence and a Faculty Fellow of the University of Colorado Institute of Behavioral Genetics.

Dr. Coors received her undergraduate education from Cornell University where she majored in biological sciences. She then attended the University of Denver, earning a M.S. in cytogenetics, a M.A. in ethics and religion, and a Ph.D. in bioethics. Coors is Chairperson of the Ethical, Legal & Social Issues (ELSI) Working Group of the Alpha-1 Foundation, serves on the Advisory Board of the Alpha-1 Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee and the Board of Directors of the COPD Foundation Patient-Powered Research Network.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.