Torres B, Atkinson E. Dear medicine: diabetes prevention is not your battle to fight. Harvard Public Health Review. Fall 2018;15.

DOI:10.54111/0001/O5

Dear Medicine,

You need help. We know that you have been trying to handle chronic diseases, especially diabetes, by yourself; however, there are 422 million adults with diabetes worldwide, and prevalence continues to grow. 1 We are writing to let you know that prevention is not your battle to fight.

While Type 1 Diabetes—an autoimmune disease—has been increasing, Type 2 Diabetes (or T2D) still causes the lion’s share of cases (90 to 95% according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2). It is clear that genetics, lack of physical activity, stress, and sleep patterns play a role, but there is a growing consensus that T2D’s principal trigger is the type of food we eat. 345

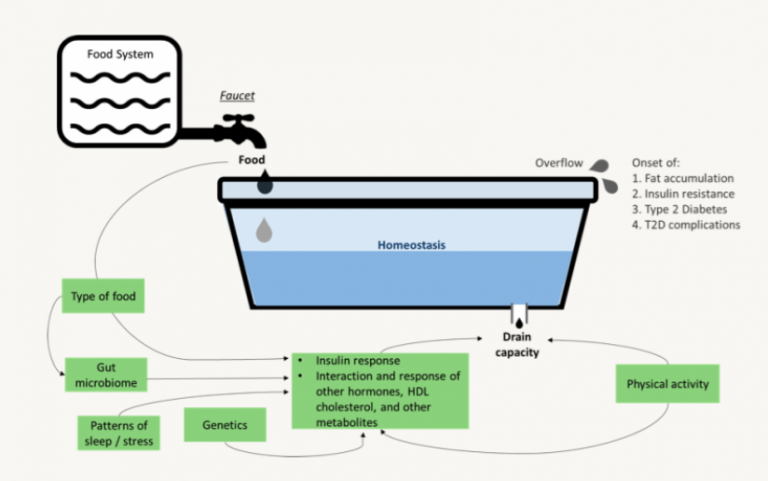

This relationship can be conceptualized as a bathtub, as shown in Figure 1. The food that we put in our bodies can be thought of like water flowing into a bathtub; the food we eat must be metabolized at a certain rate in the same way that water must flow out of the tub to avoid overflowing. However, in this case, it is not as simple as “calories in, calories out.” The metabolism rate—or drain capacity—is affected by the amount, type, and glycemic load of the food we eat. Consuming high-glycemic load food causes the secretion of excess insulin, which ends up circulating in the blood, causing fat accumulation and insulin resistance, which over time cause T2D. Independent of genetics or physical activity, the unhealthy food pouring out of this faucet is the principal driver of the T2D epidemic 6 7 So, Medicine, why act as if it is the same to focus on the faucet as on the drain?

In the past, when infectious diseases were the greatest danger to health, diseases were your responsibility. Physicians or public health professionals were responsible for educating the public about a specific risk factor, and the public was then expected to follow those recommendations. Recent T2D prevention strategies use this same approach: give people information on food and assume they will follow it. Putting calorie counts on menus, changing package labeling requirements, and educating the public on the food pyramid/plate have yielded mixed results 8 9 This may be because our environments are built around the very foods that we are supposed to be avoiding.10 11 Instead of being an anomaly, T2D is a natural response, by normal people, to our current abnormal food environments. 12

Medicine, trying to take T2D on by yourself is hurting the relationships between your physicians and patients. Health providers typically follow clinical guidelines and inform their patients about the importance of decreasing caloric intake and increasing physical activity. However, when patients leave the doctor’s office and try to navigate the food choices available to them in this built food environment, it is difficult for them to follow this advice. Patients feel that providers are asking for something impossible and health providers assume their patients do not care about their health. This dissonance damages the patient’s trust in their provider and contributes to physician burnout and feelings of futility. 13

Part of why dietary advice seems so “impossible” is that medical research and advice focuses on what not to eat or drink. Even the strongest-willed of us would have difficulty following all existing dietary restrictions while attempting to live in the current built food environment. The focus on what not to eat has left out what we should eat. In general, medical researchers have stopped short of asking other sectors how to produce and eat more nuts, seeds, legumes, and vegetables. Nor are they asking how to make healthy foods more available, accessible, affordable and convenient. Remember, malaria was controlled, in large part, with effective drainage systems and paving over stagnant pools of water, not by spraying pesticide or treating individual patients with medication. And water fluoridation came about because public health officials focused on what would contribute to generalized oral health instead of treating individual teeth. 14

Skeptical that food could have that big of an impact? A recent study of a “Farmacy” that provided free food as a treatment for T2D throughout 18 months saw a 40% decrease in the risk of death or serious complications, and an average drop of 2.1% in glycated hemoglobin 15

So, what are we proposing? A dramatic change in strategy 16:

It can be done. Fortunately, there are voices who are mobilizing other sectors and incorporating a food systems approach to find solutions. The global network INFORMAS is providing guidance to promote healthy food environments. 30 The WHO Independent High-level Commission on NCDs (2018)31 is asking to “redouble efforts to engage sectors beyond health.” International platforms, such as EAT Forum, are emphasizing collaboration between government, science, and industry to find solutions to food systems issues. The Rockefeller Foundation 32 and the World Economic Forum 33 have independently commissioned reports to uncover innovations that can transform our food systems.

So, Medicine, where should you go from here? Start asking for help. Ask other sectors difficult questions: Will you help my patients access a variety of healthy foods? How can you incentivize the food industry to produce and market healthier products? Will you teach my patients how to buy and prepare fresh food without it going bad? Can we define a low-glycemic food basket that all citizens should have the right to afford?

Please keep running programs to screen and manage at-risk people; hold on to programs aimed at controlling sugar levels in patients and curbing T2D complications. But do not allow national governments to delegate prevention to your sector. Tell national governments to put the burden of prevention under the food system. Support the planning of food systems for health.

Of course, you can always continue with the traditional prevention paradigm if you want, promoting lifestyle changes and putting information and individual choice at the core of the prevention efforts. But by 2050, there will be no amount of increased capacity in healthcare delivery and no imaginable fiscal policy in countries that can handle the aging demographic bulge and increasingly prevalent T2D.

We must ensure that the easiest, most convenient, cheapest, and most delicious food options also are the healthiest. You need help from the entire food system; you cannot do this by yourself.

Sincerely,

A Food System for Health

Braulio Torres is a 2017-18 Special Program for Urban and Regional Studies (SPURS) Research Fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Elena Rose Atkinson is a researcher at Fundación IDEA.

BCPHR.org was designed by ComputerAlly.com.

Visit BCPHR‘s publisher, the Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH).

Email [email protected] for more information.

Click below to make a tax-deductible donation supporting the educational initiatives of the Boston Congress of Public Health, publisher of BCPHR.![]()

© 2025-2026 Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPHR): An Academic, Peer-Reviewed Journal

All Boston Congress of Public Health (BCPH) branding and content, including logos, program and award names, and materials, are the property of BCPH and trademarked as such. BCPHR articles are published under Open Access license CC BY. All BCPHR branding falls under BCPH.

Use of BCPH content requires explicit, written permission.